-

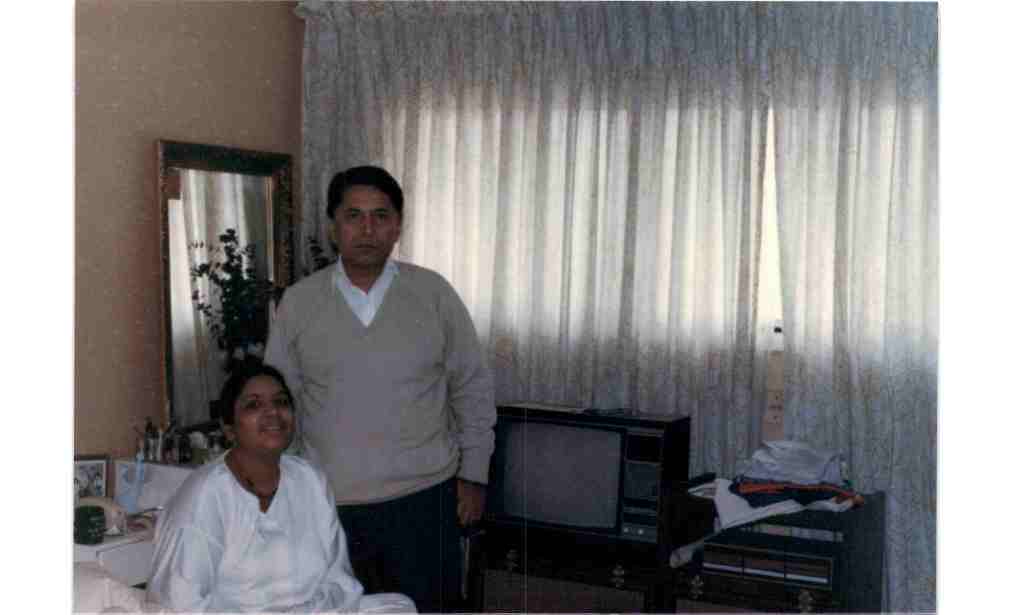

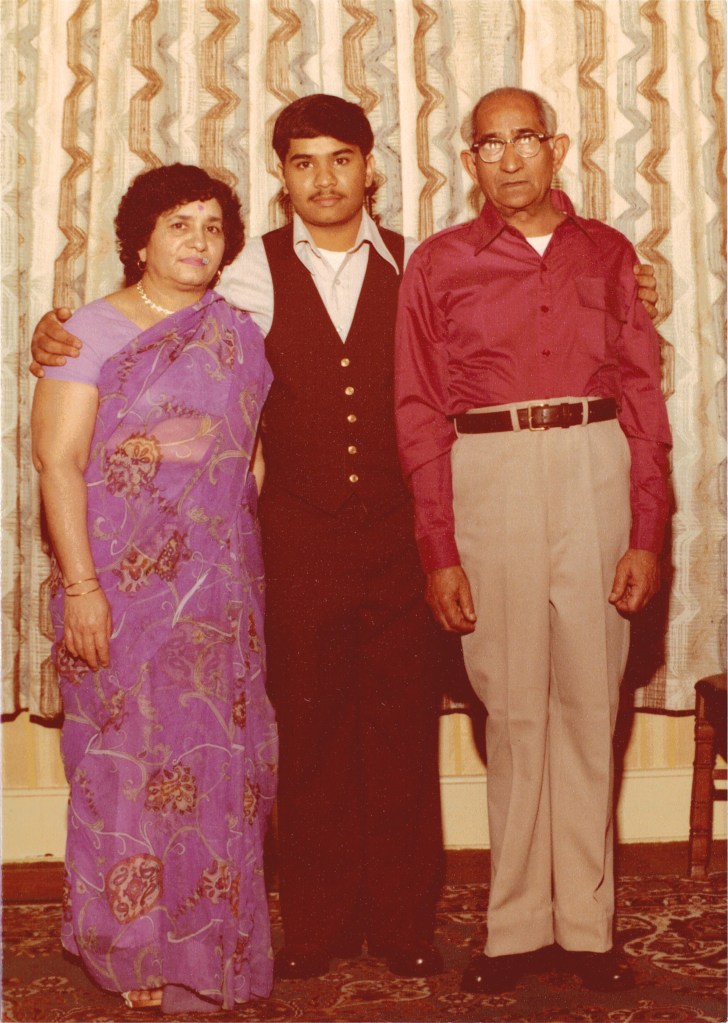

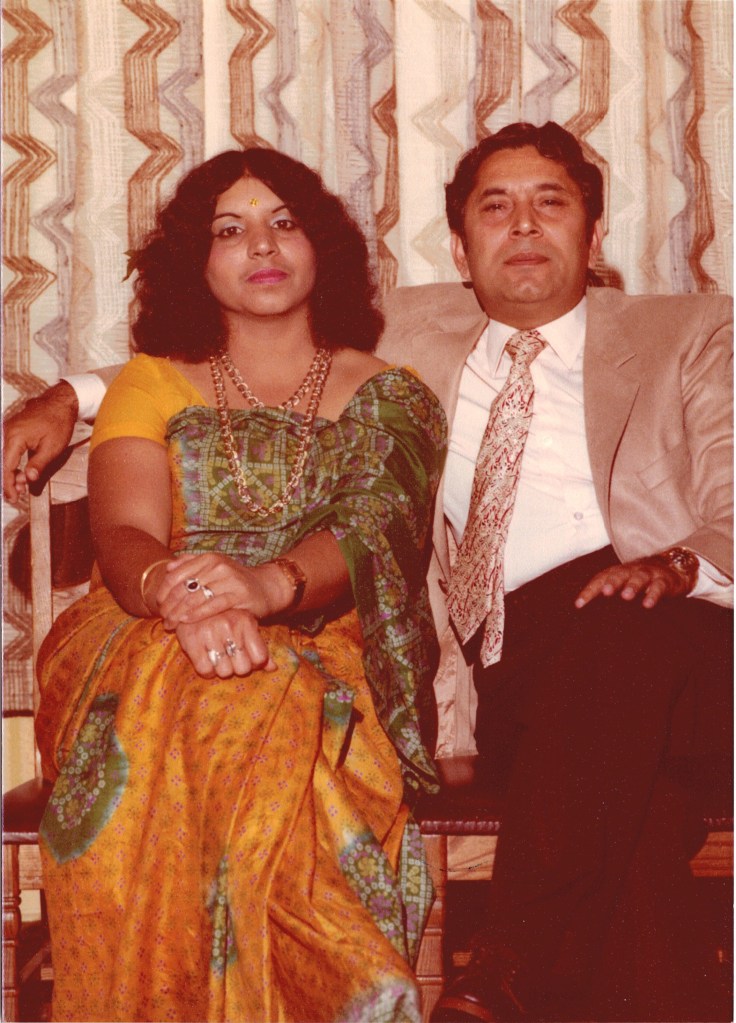

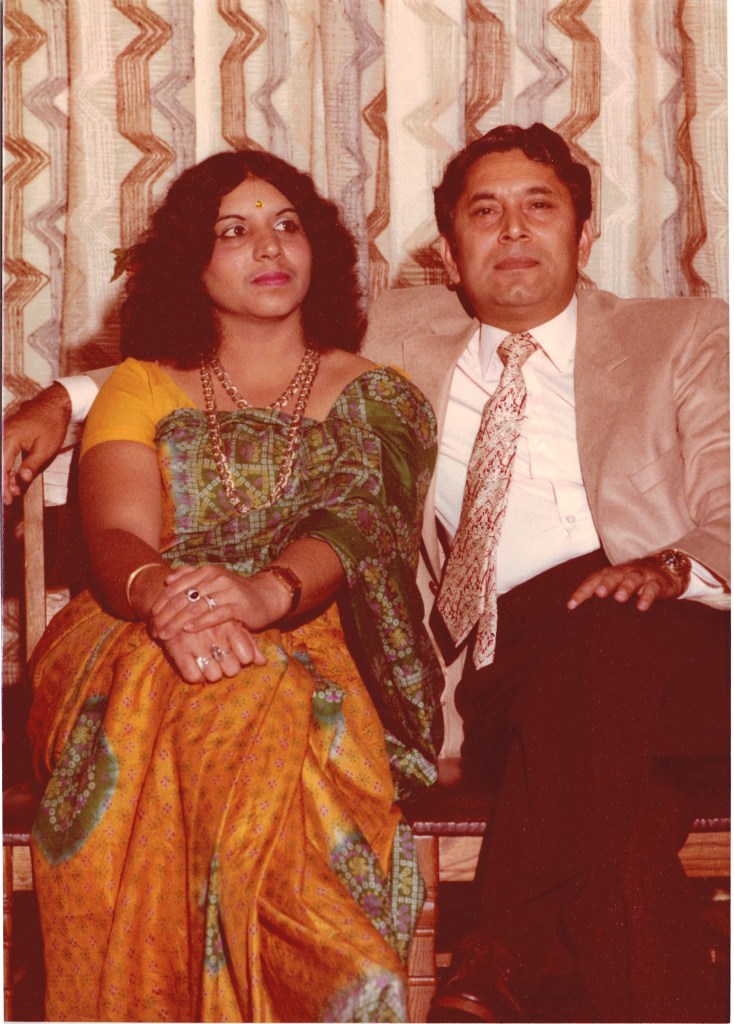

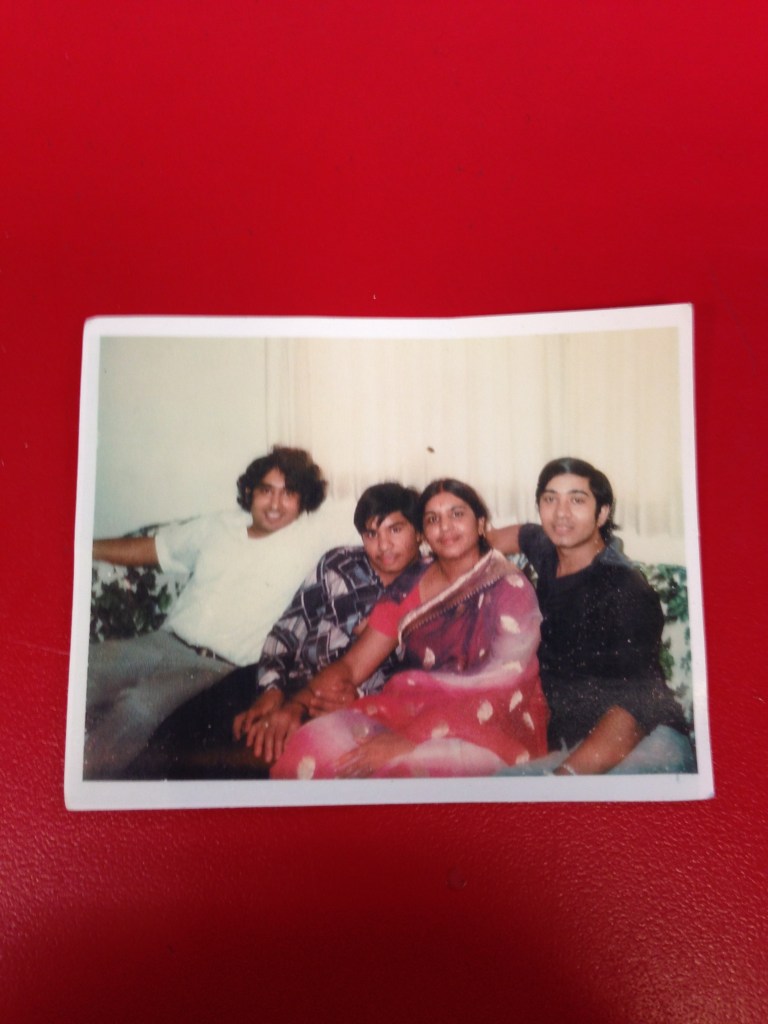

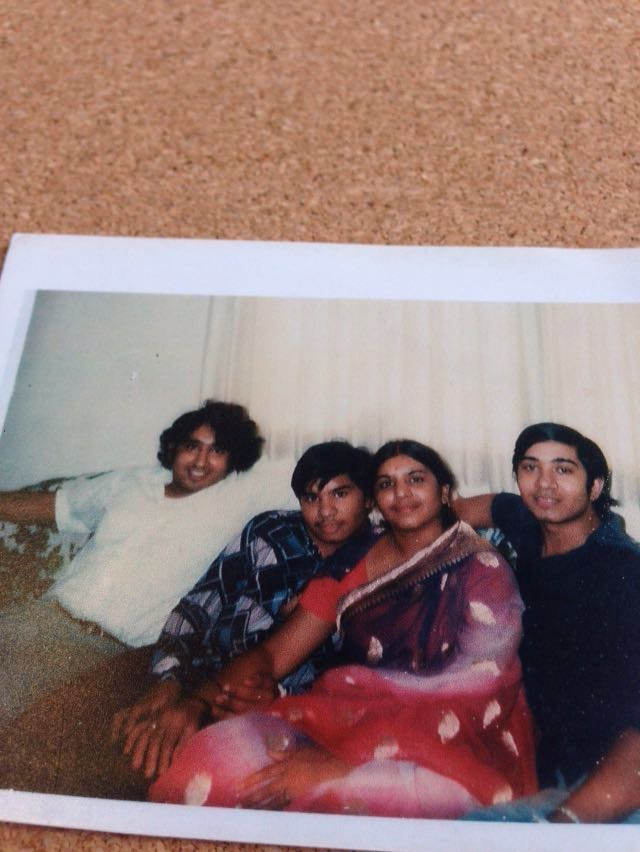

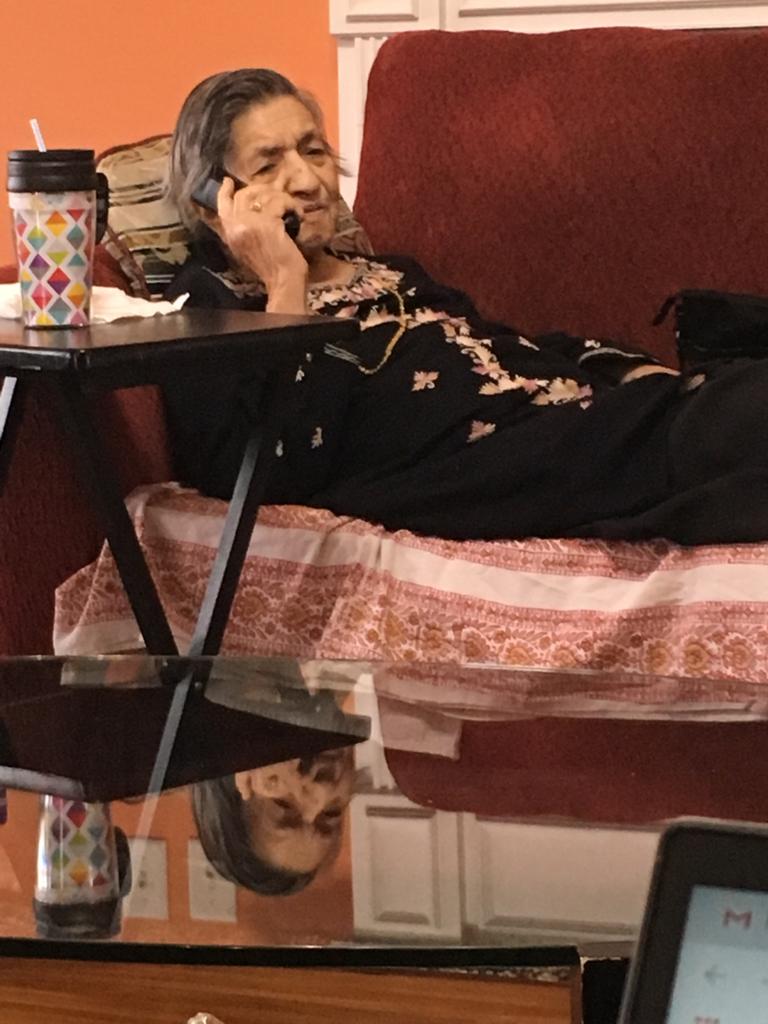

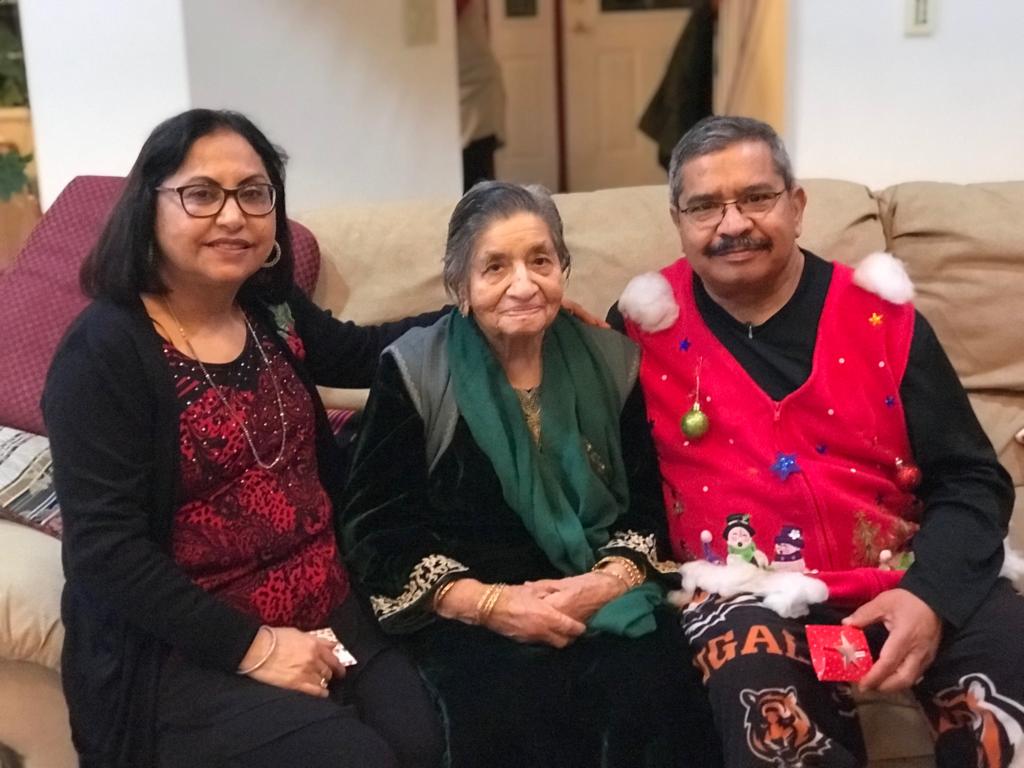

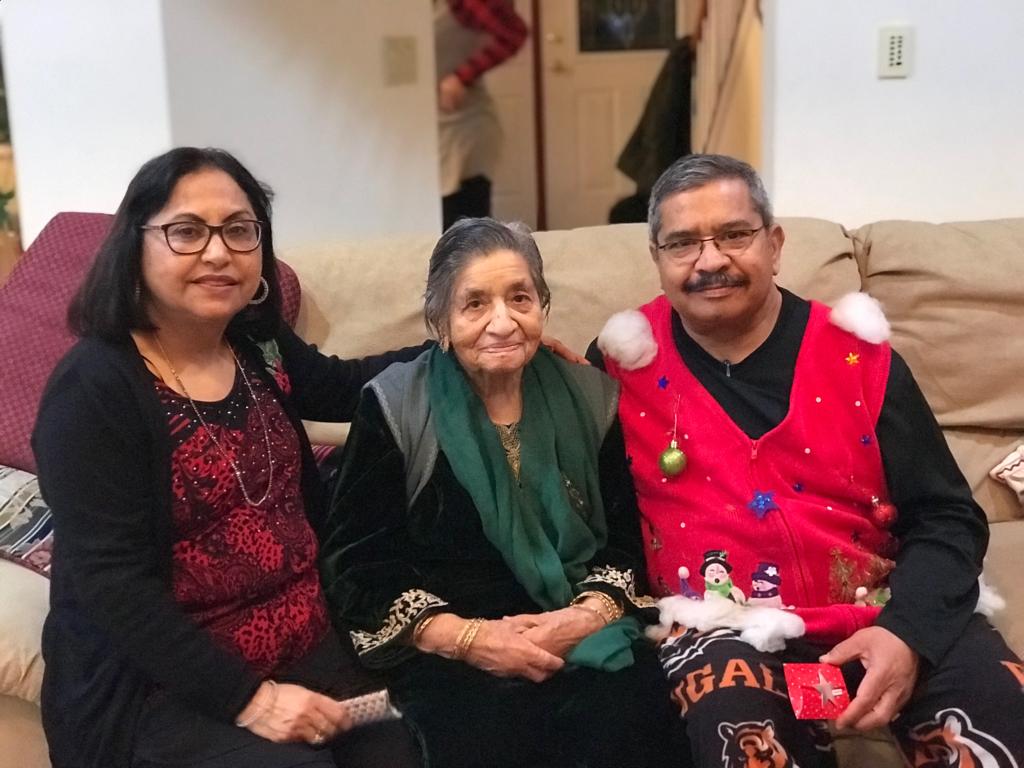

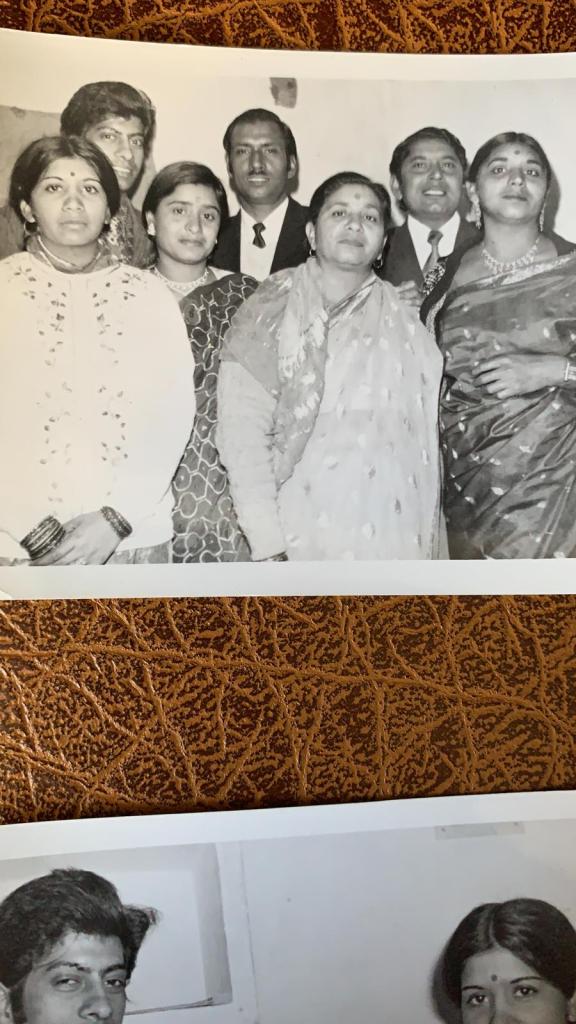

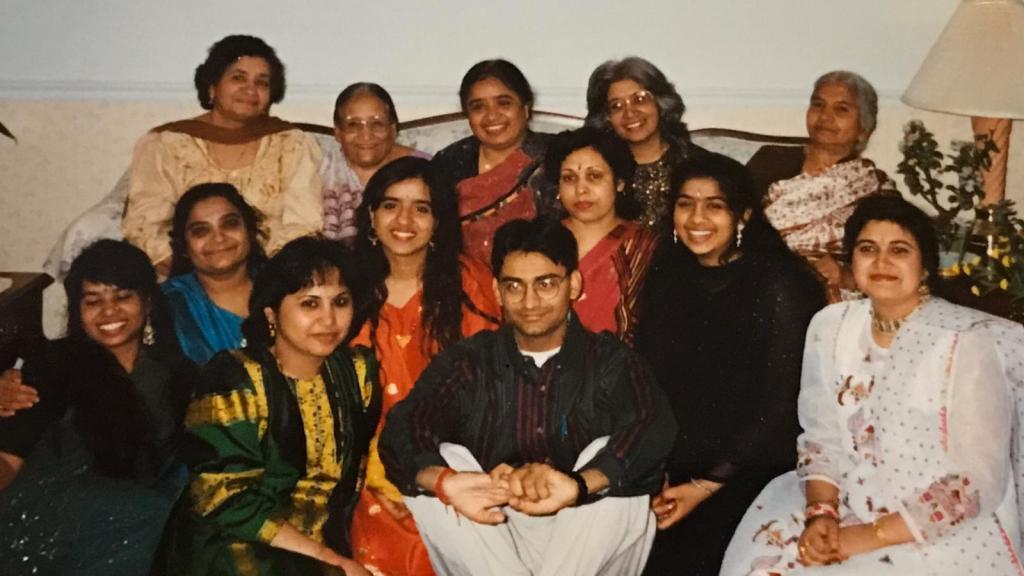

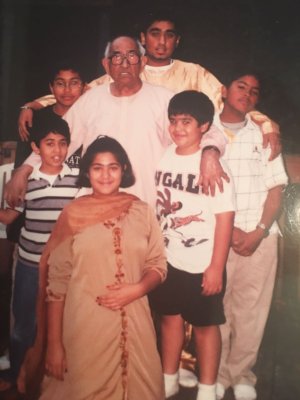

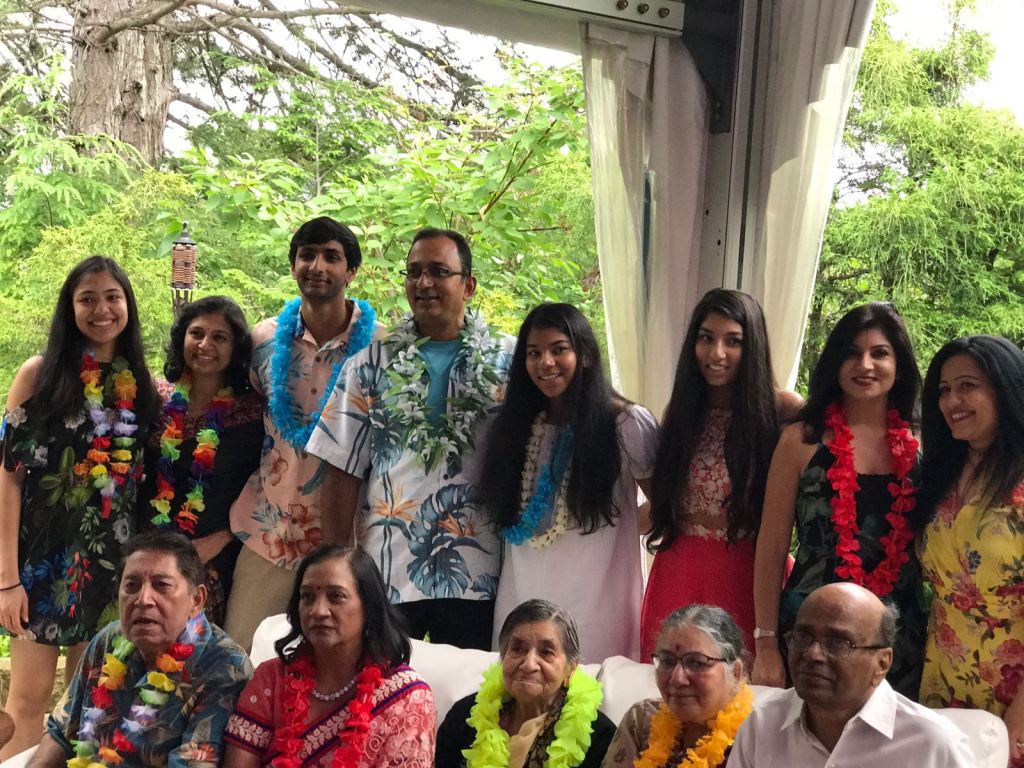

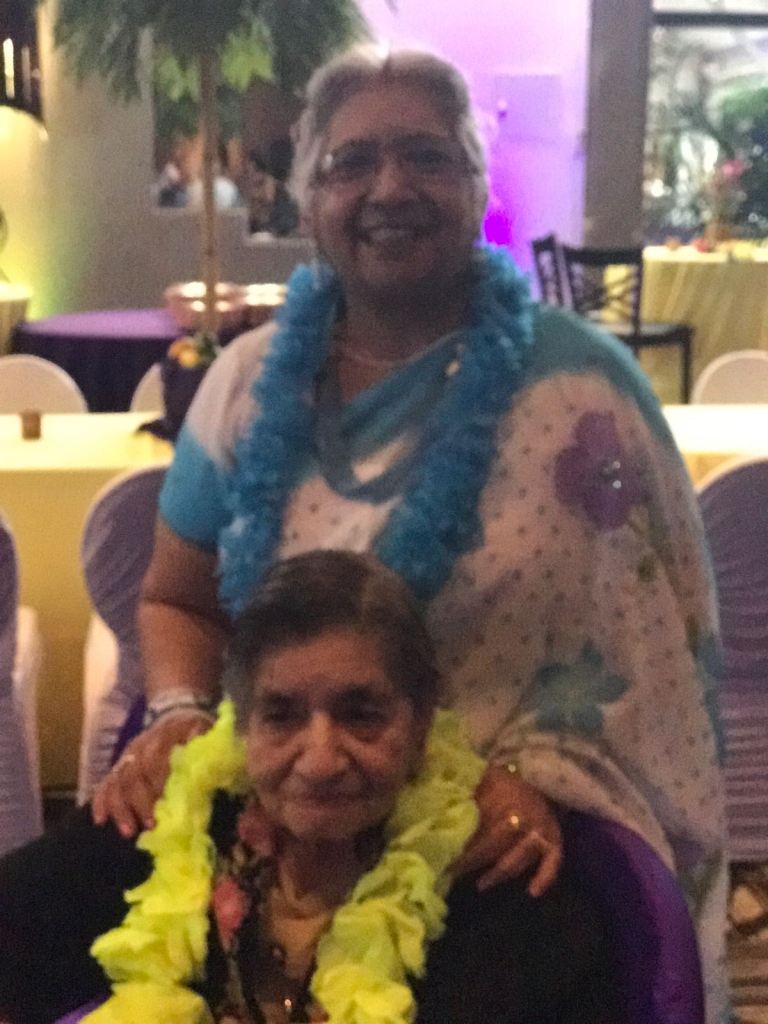

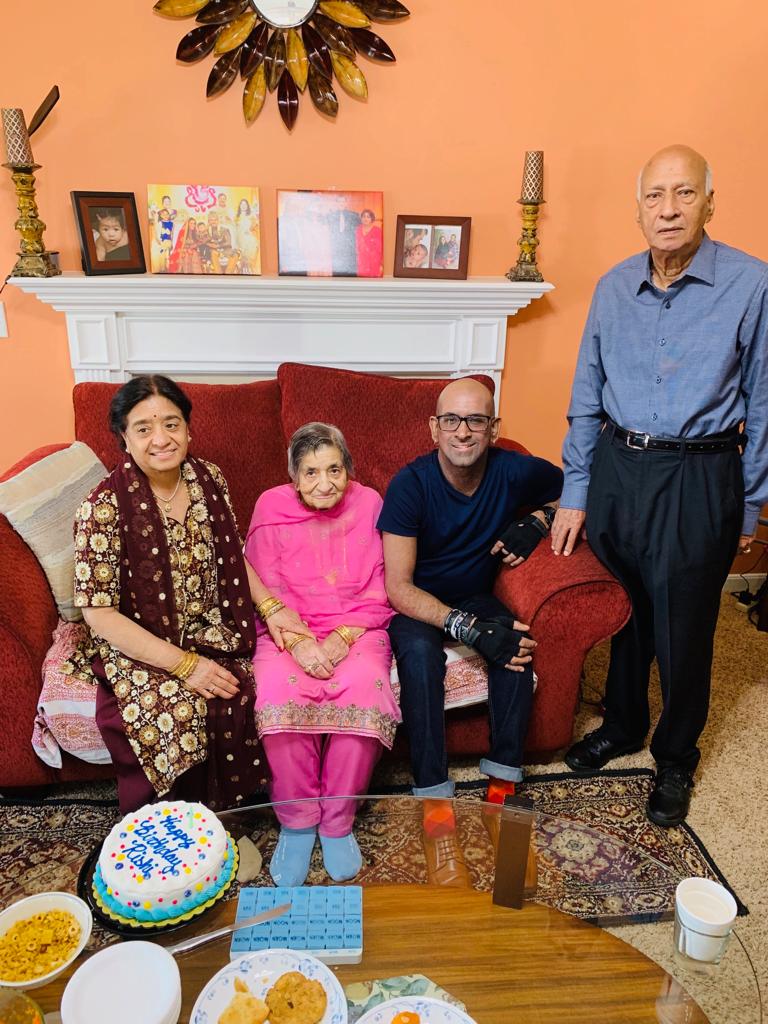

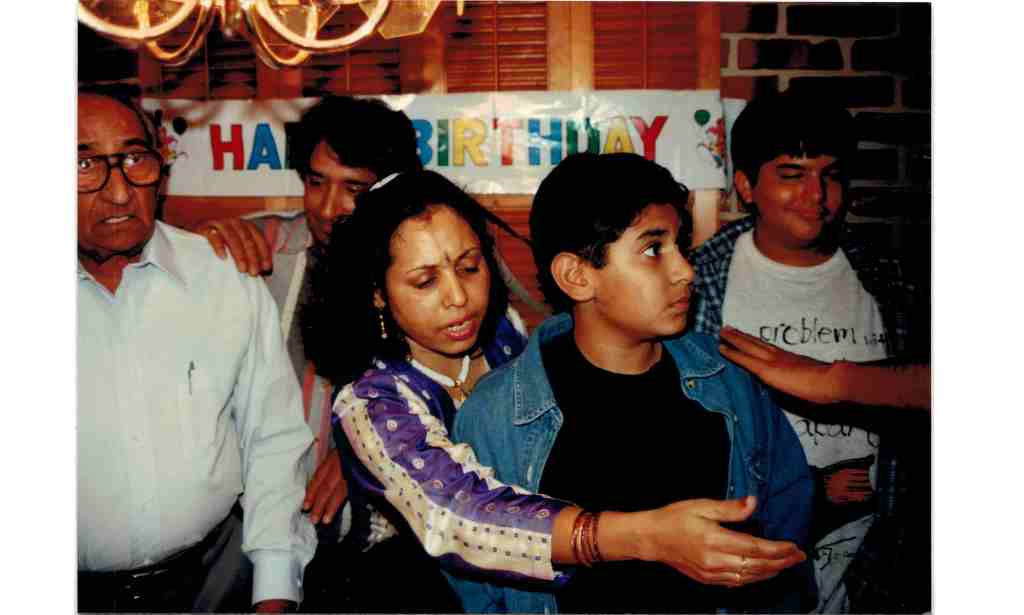

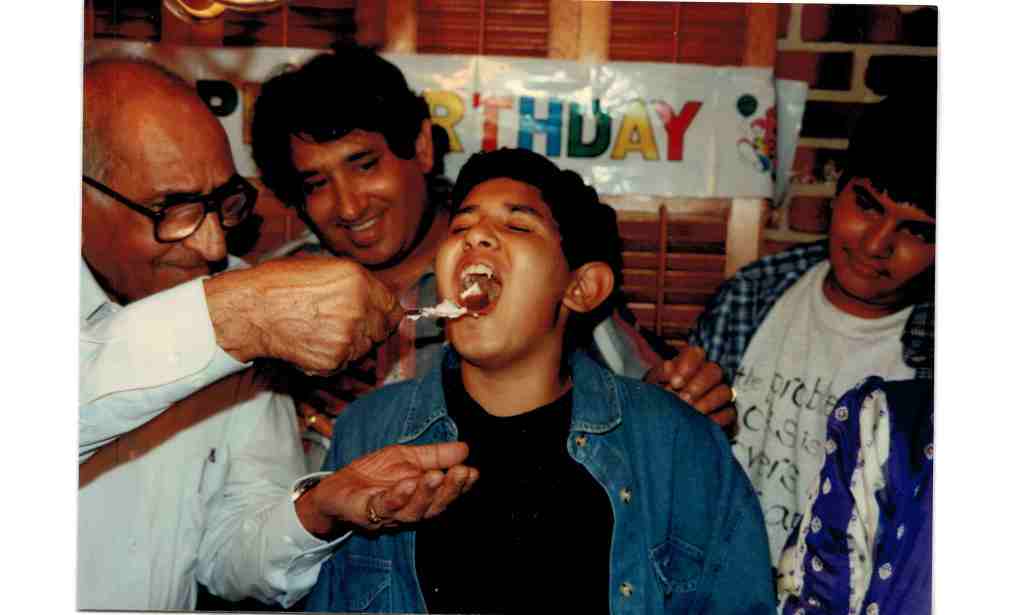

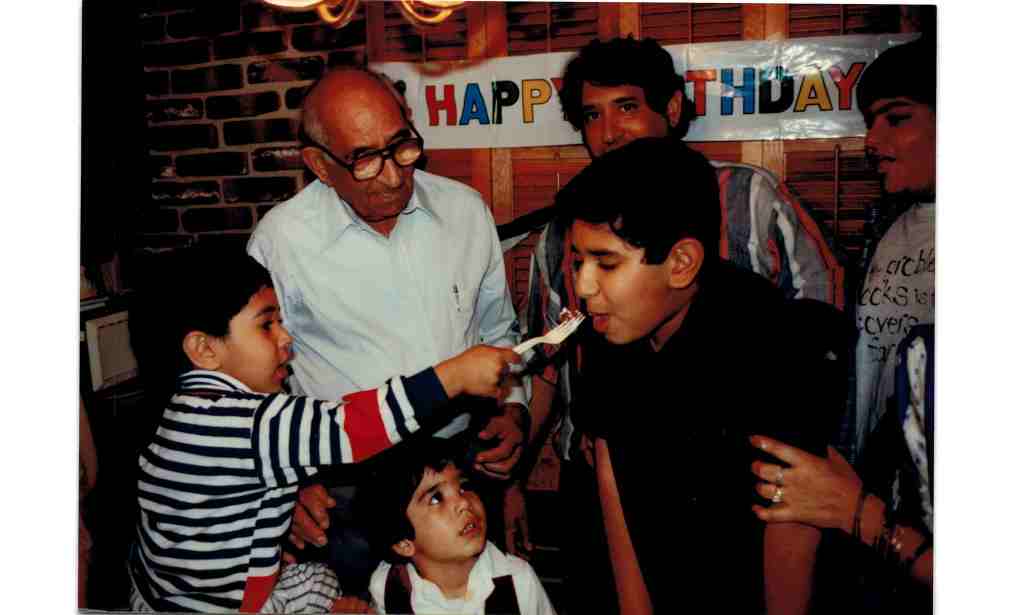

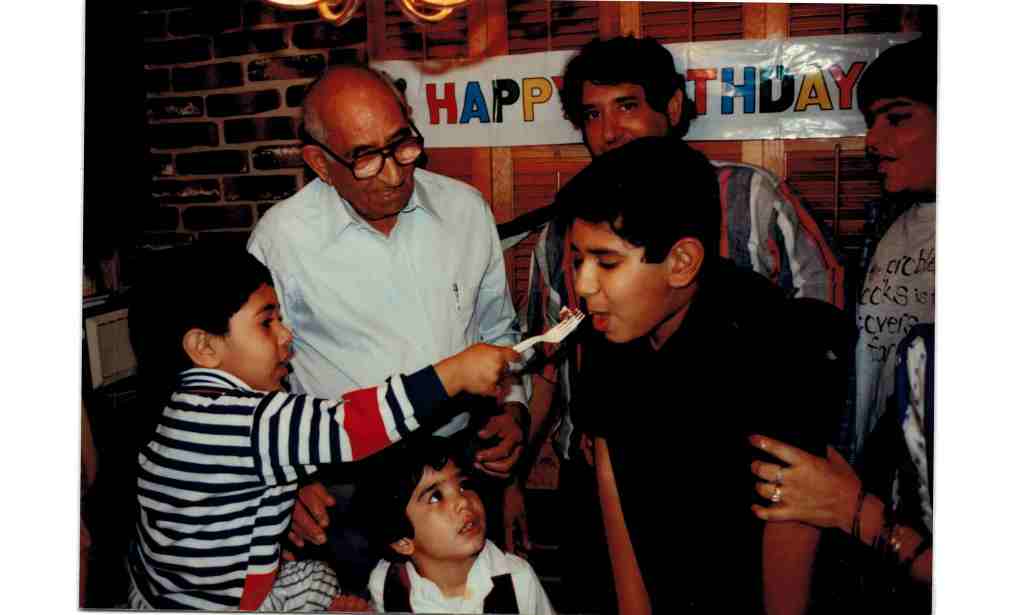

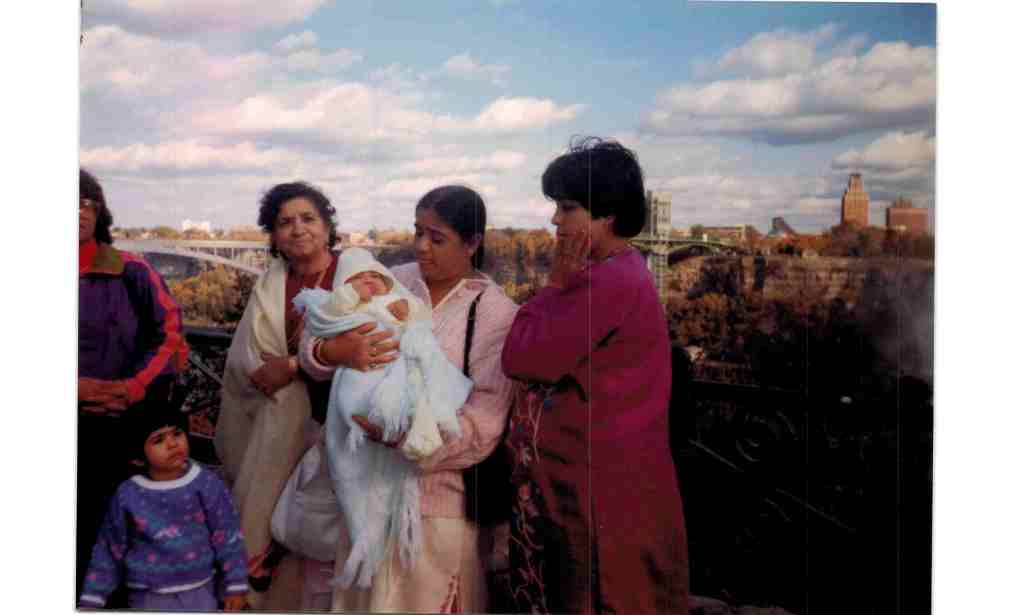

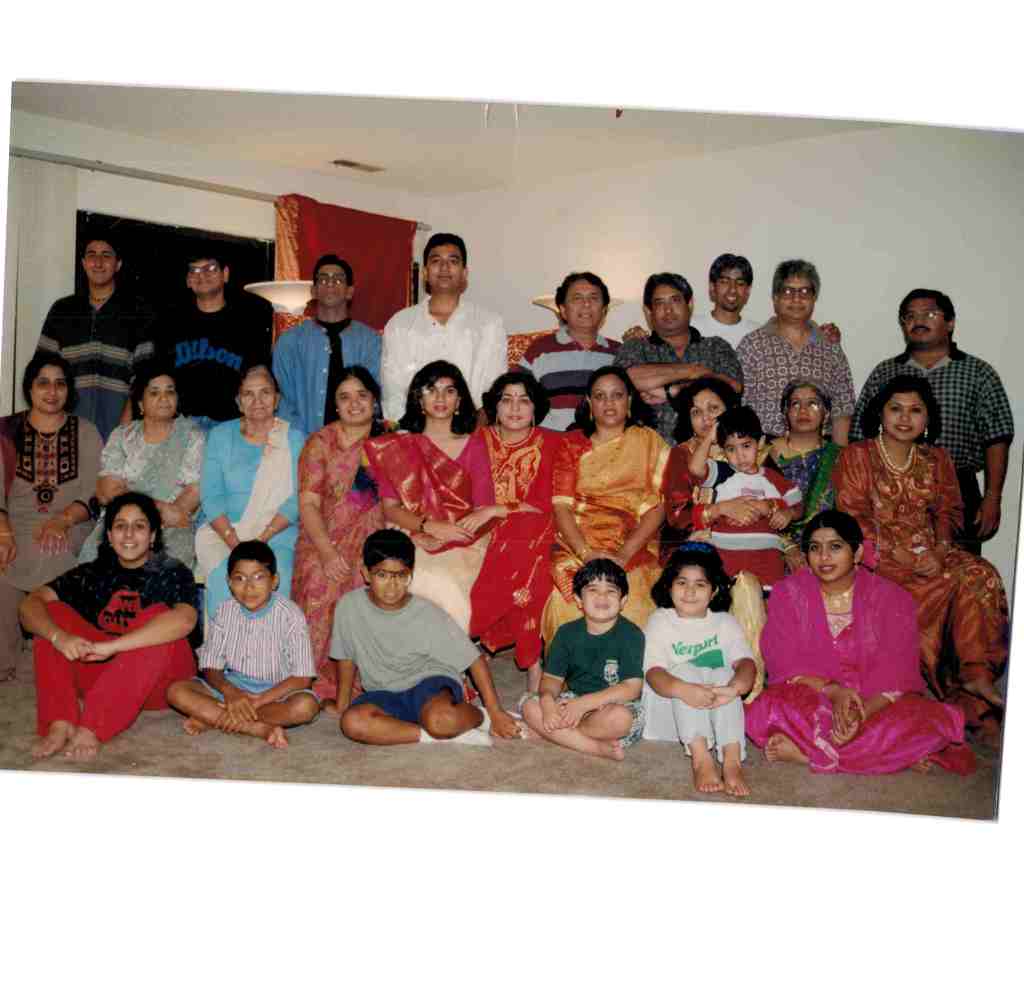

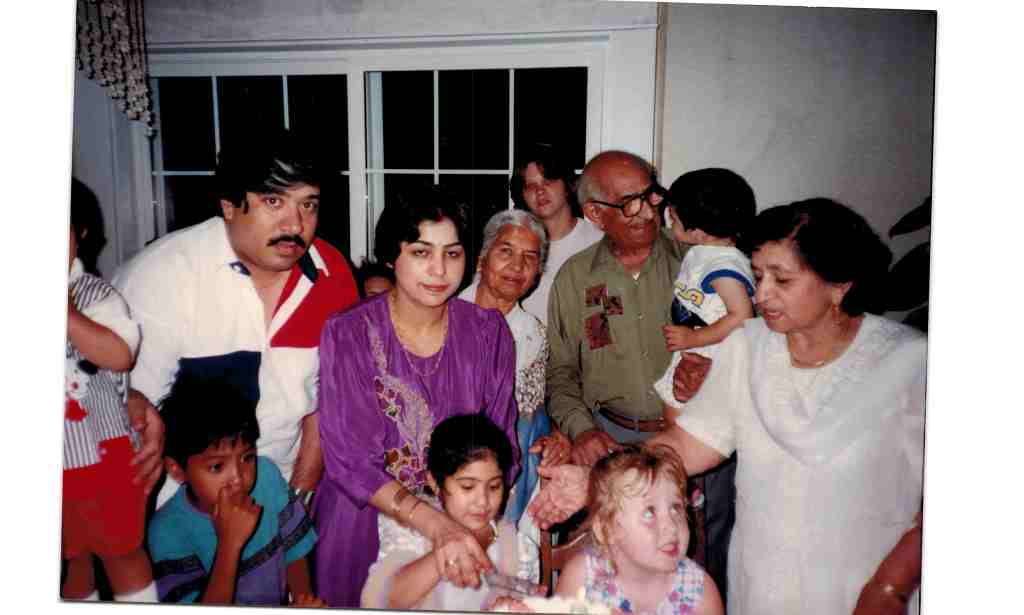

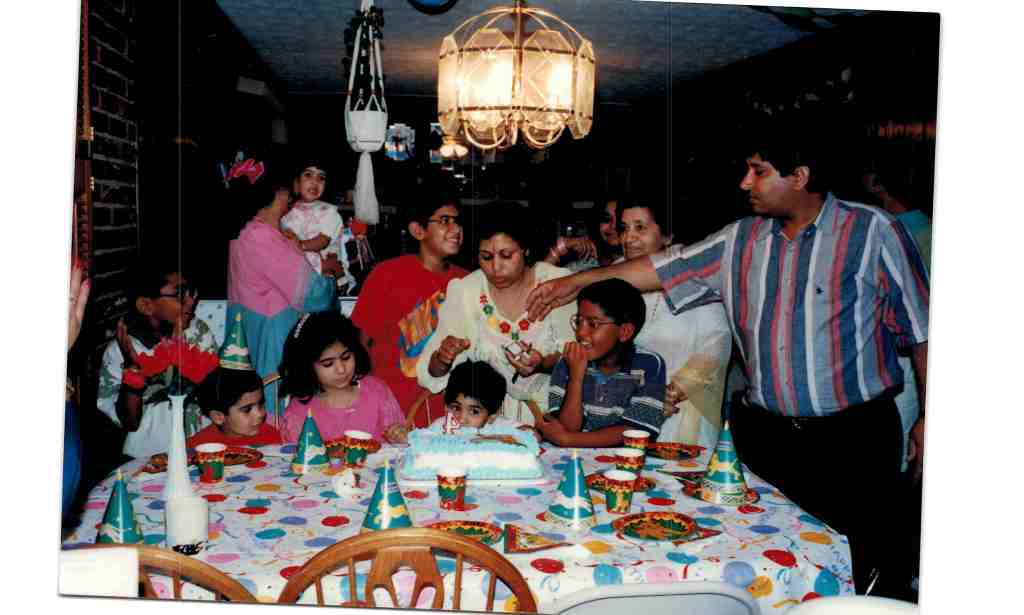

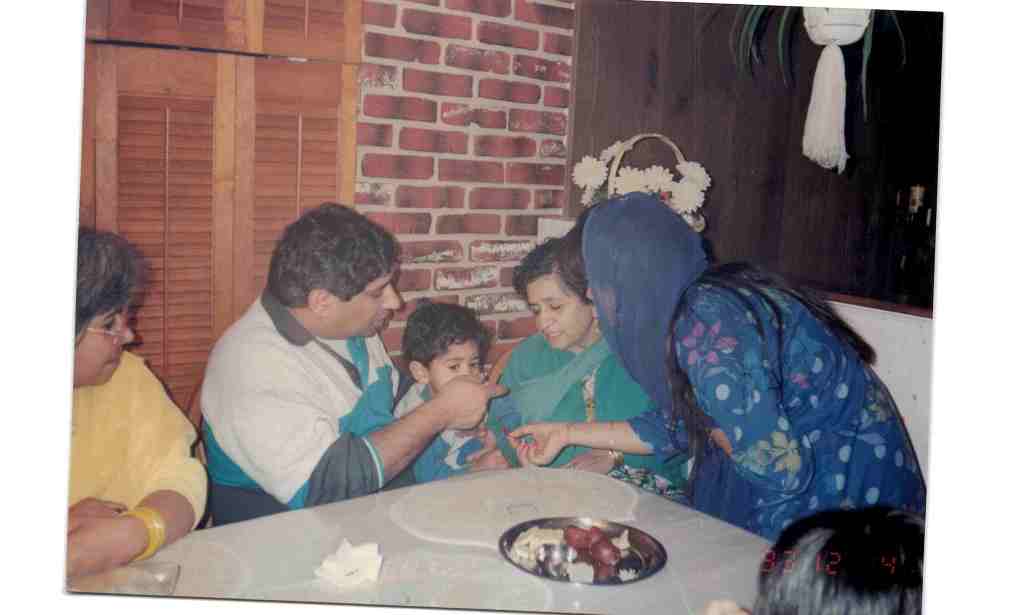

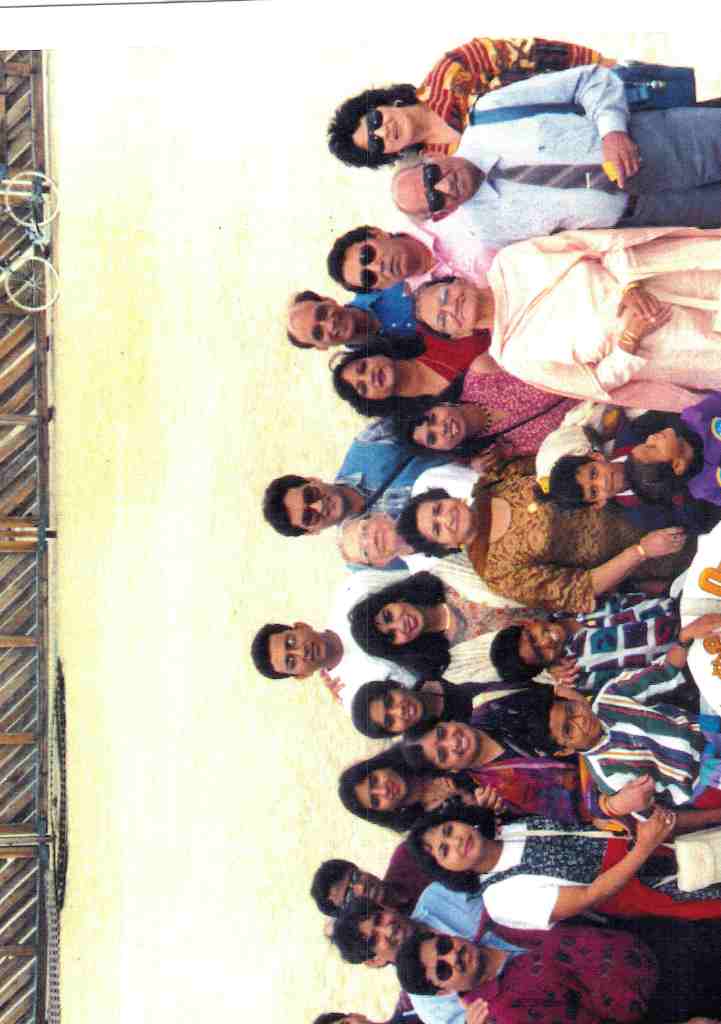

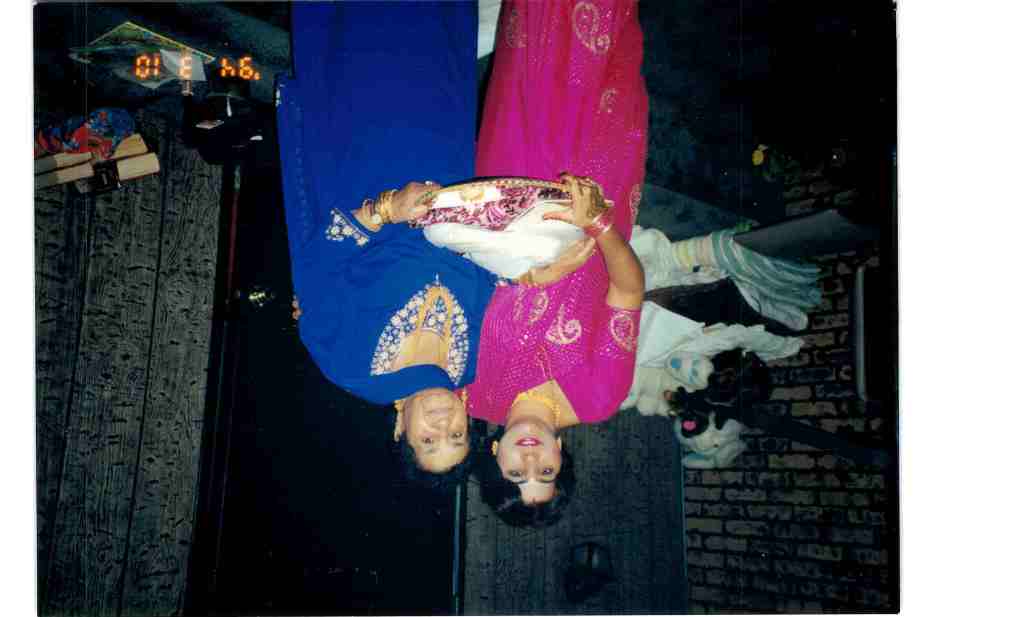

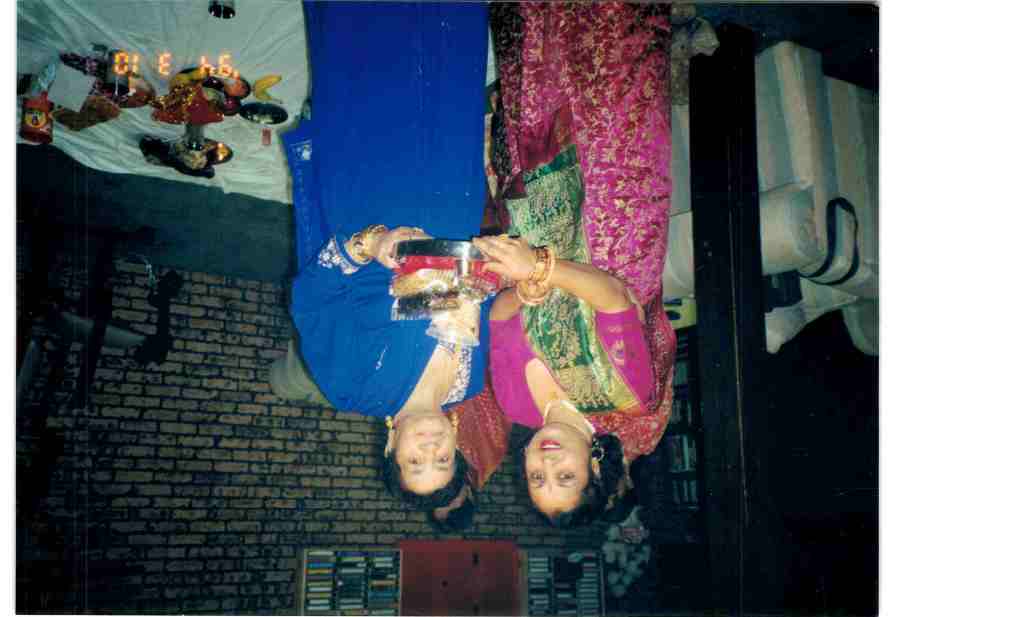

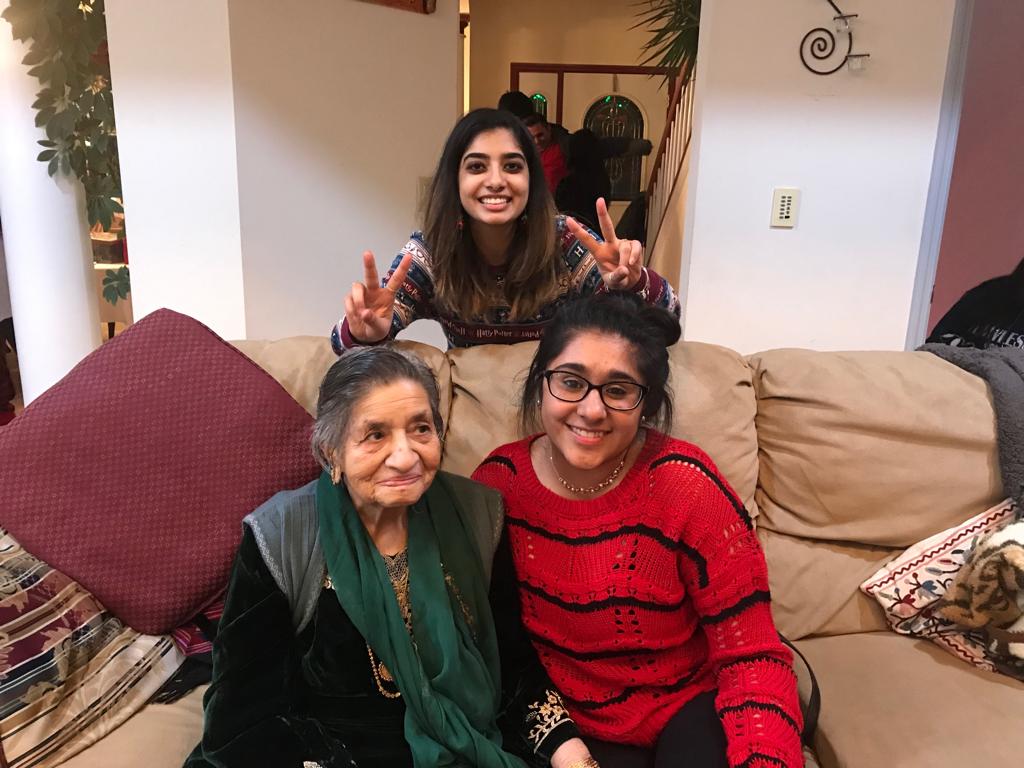

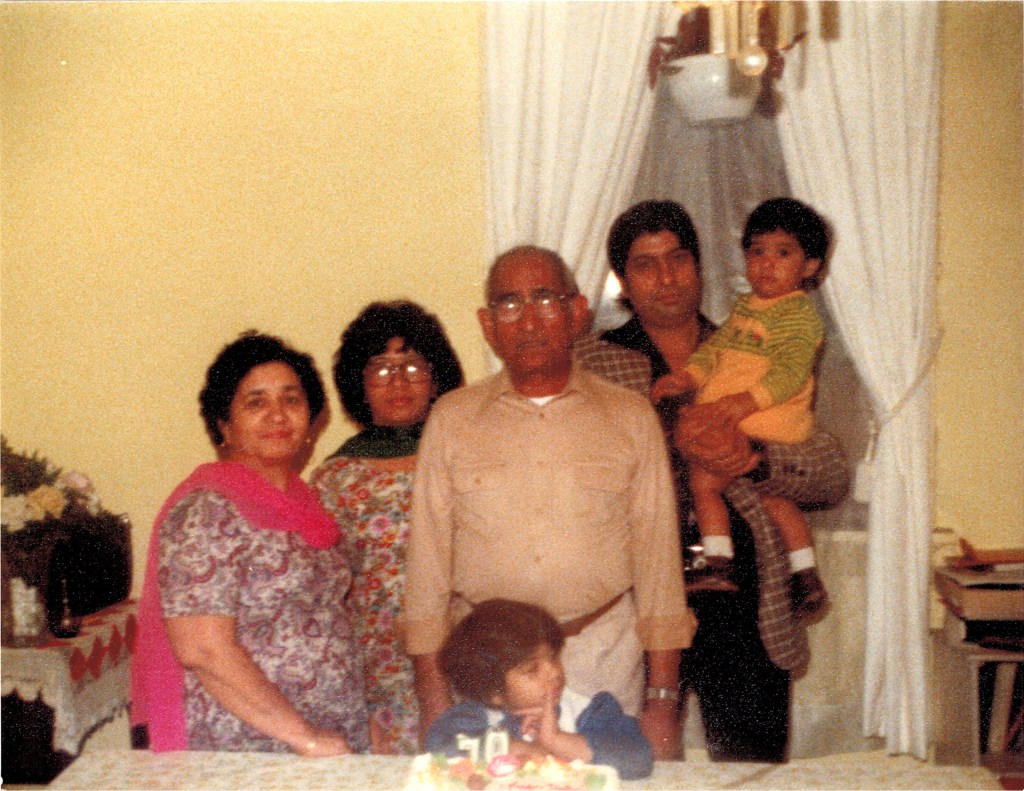

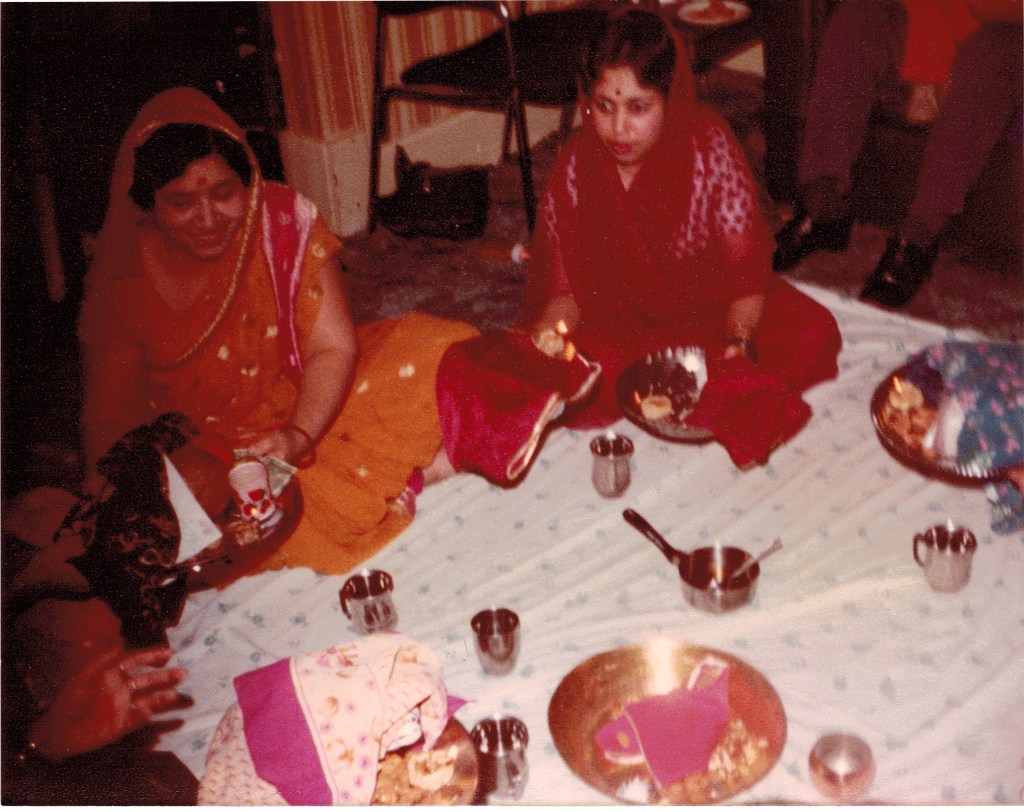

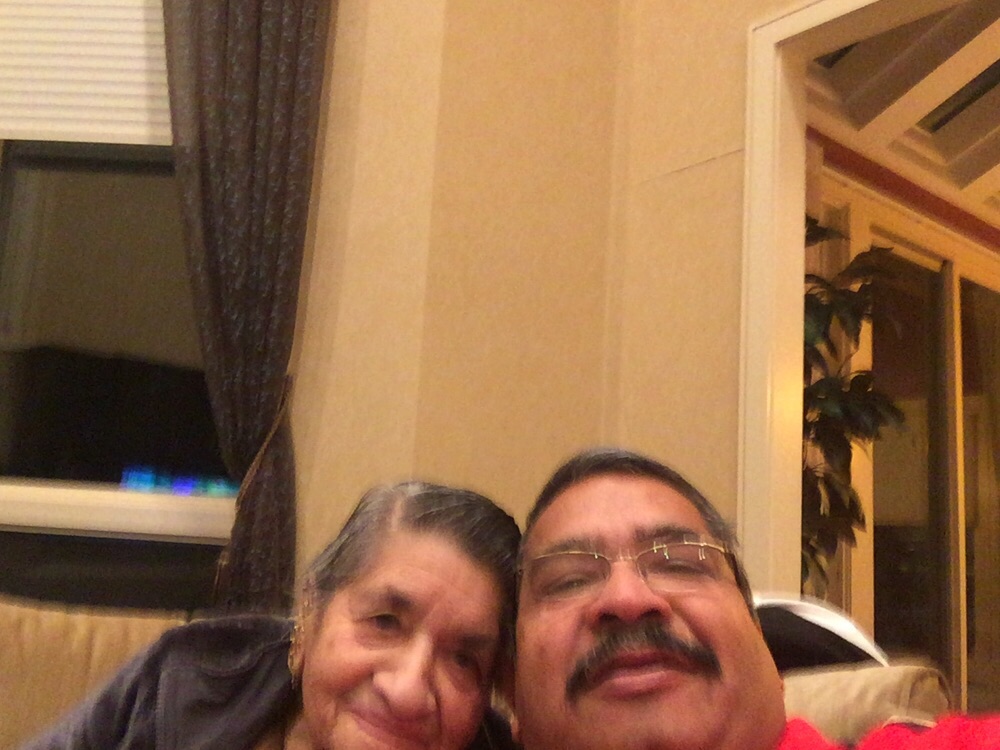

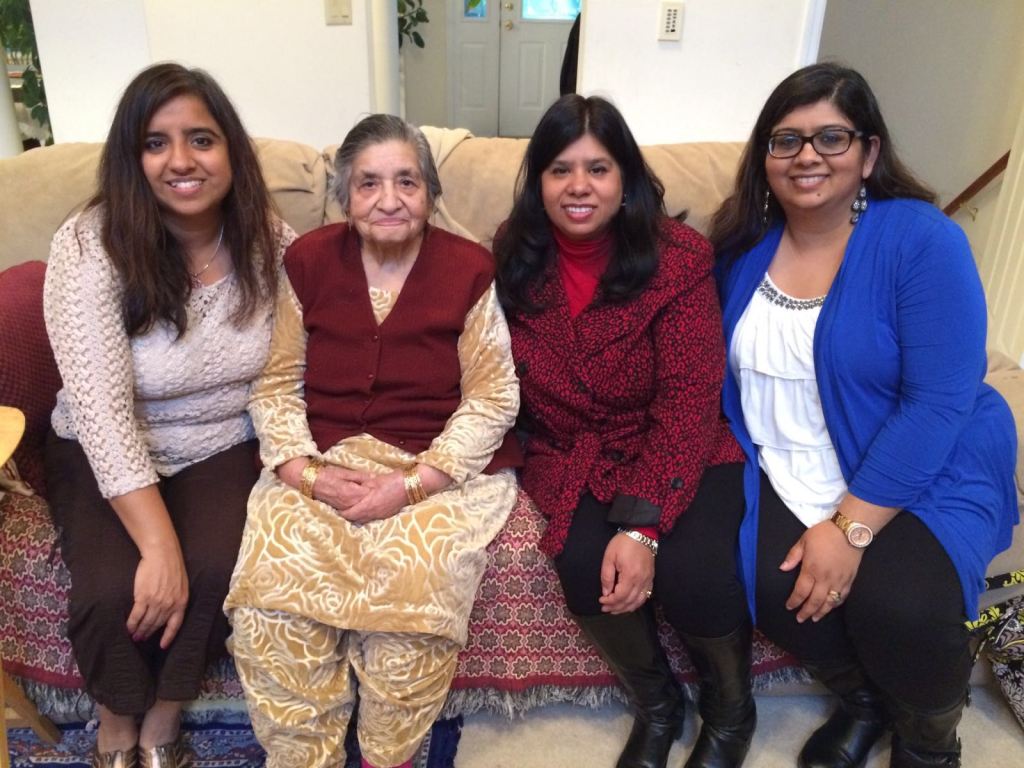

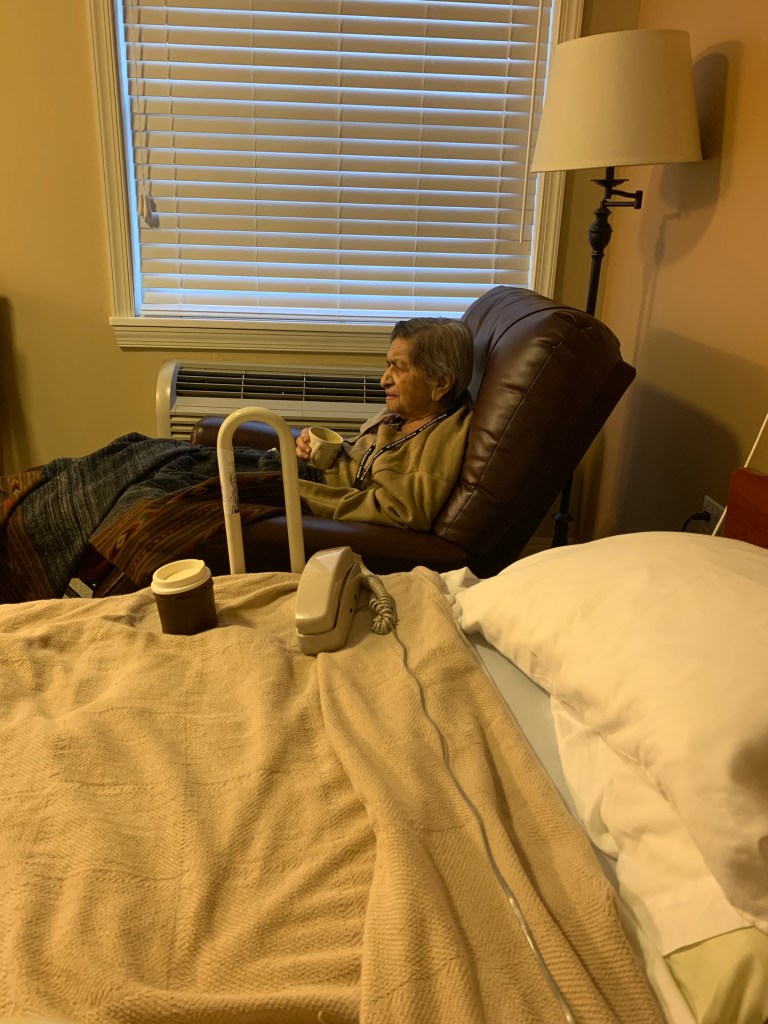

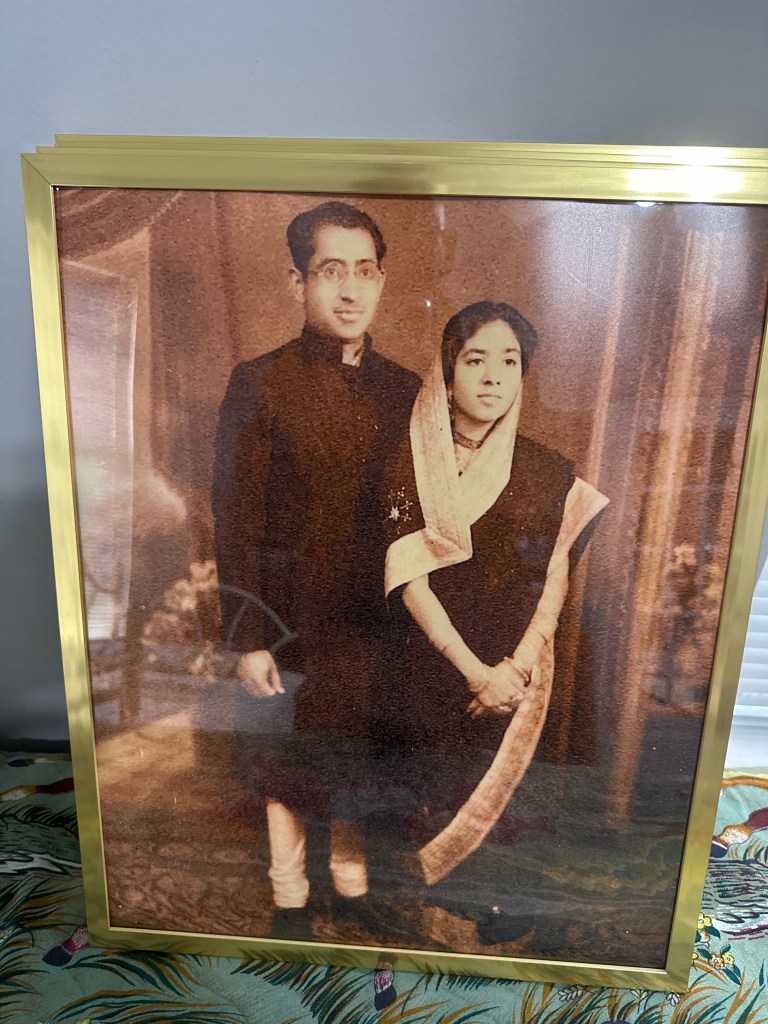

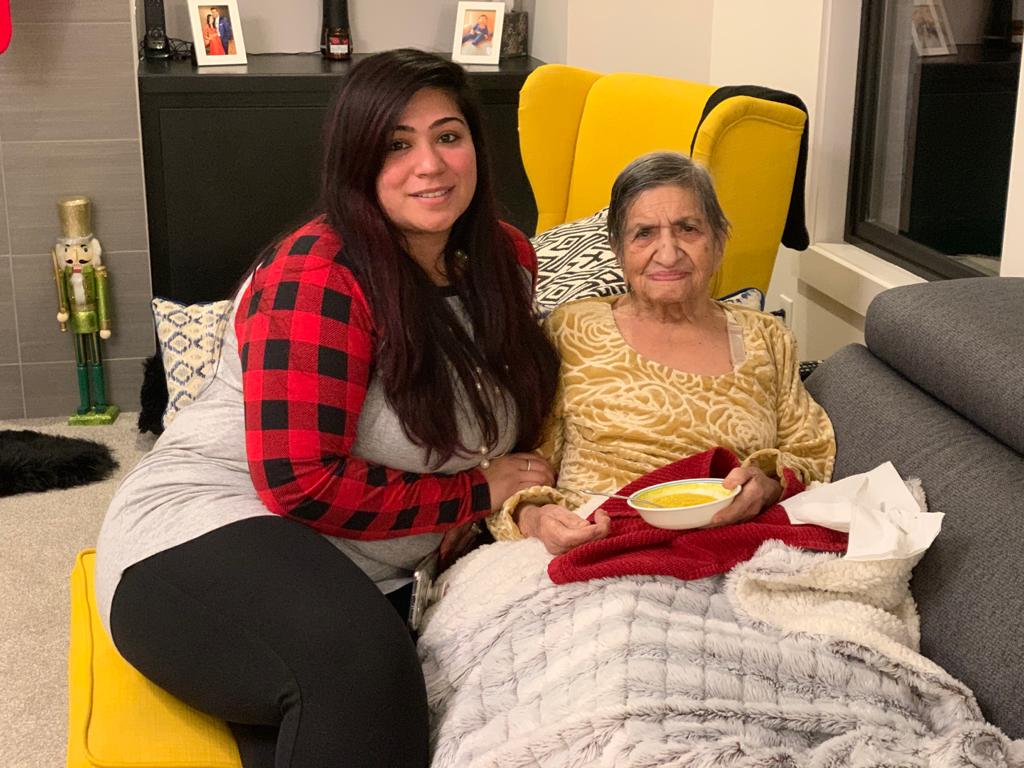

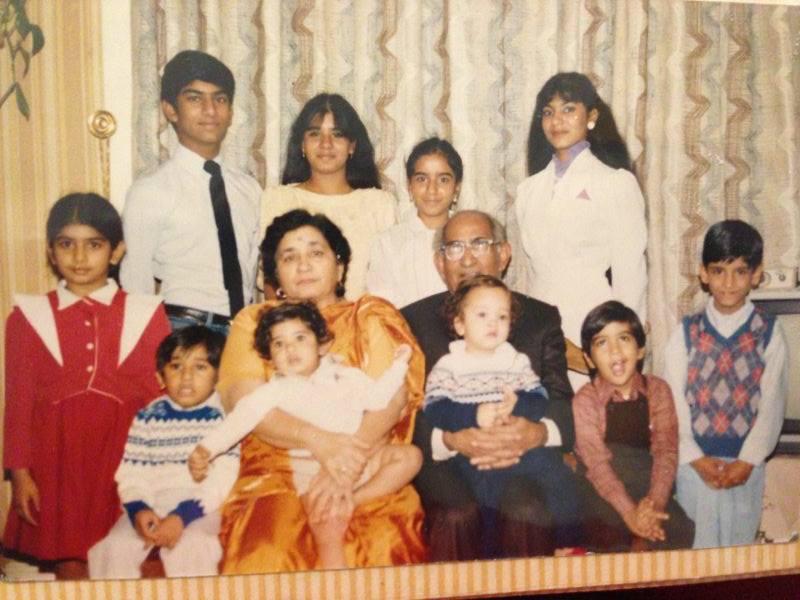

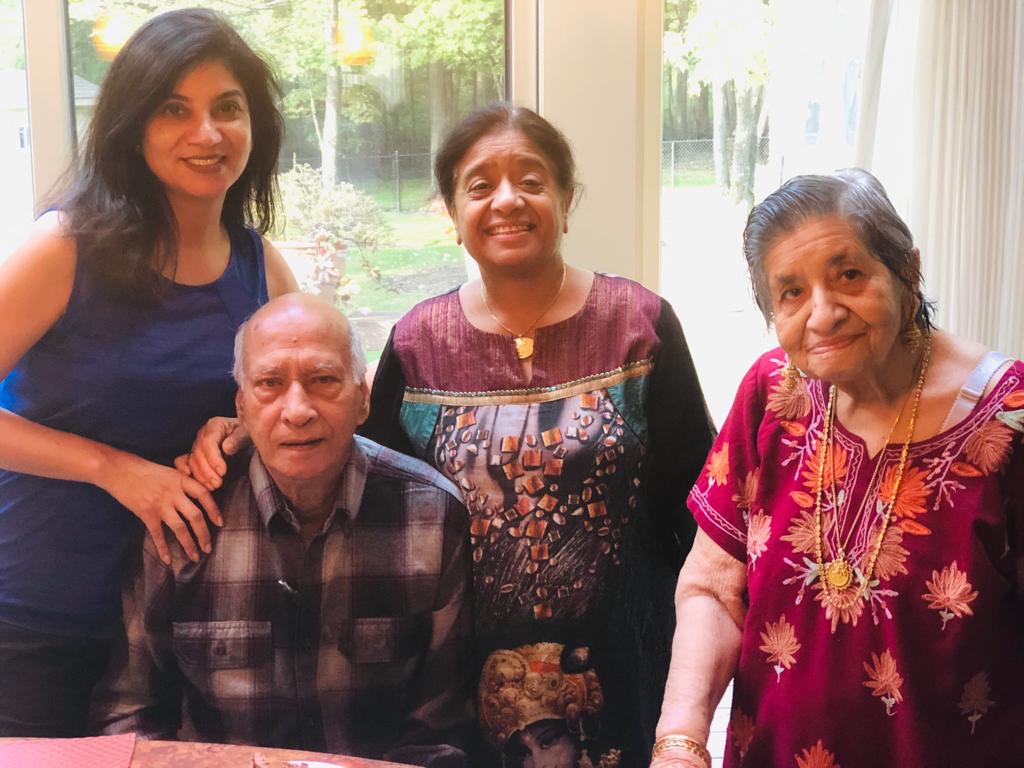

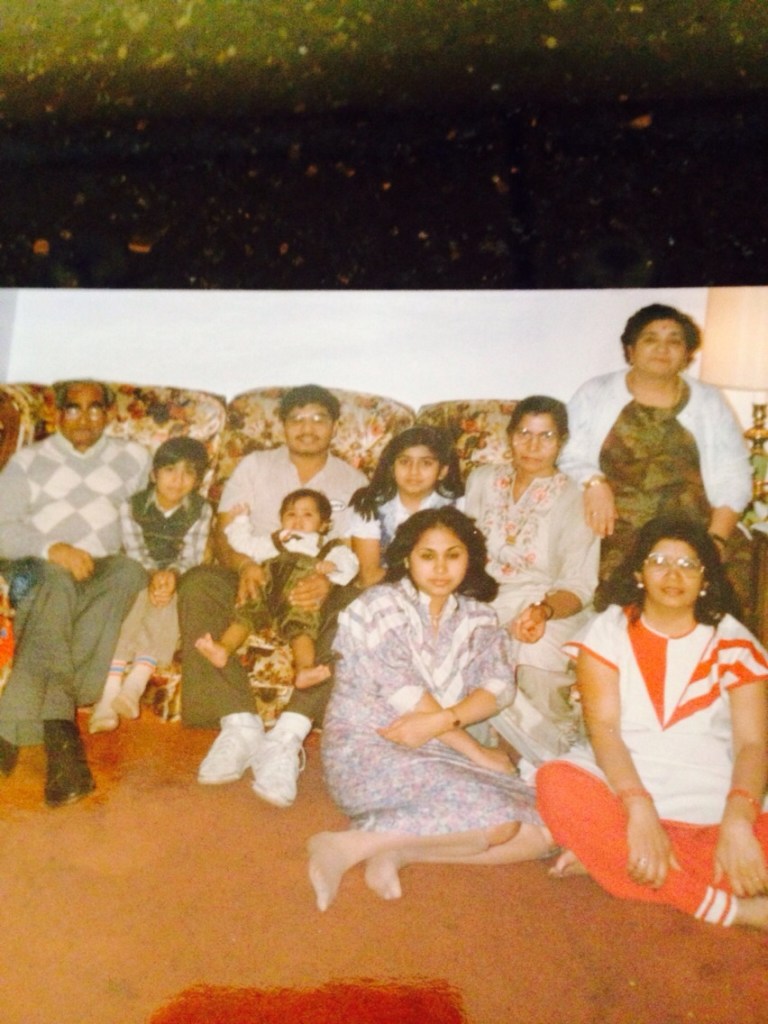

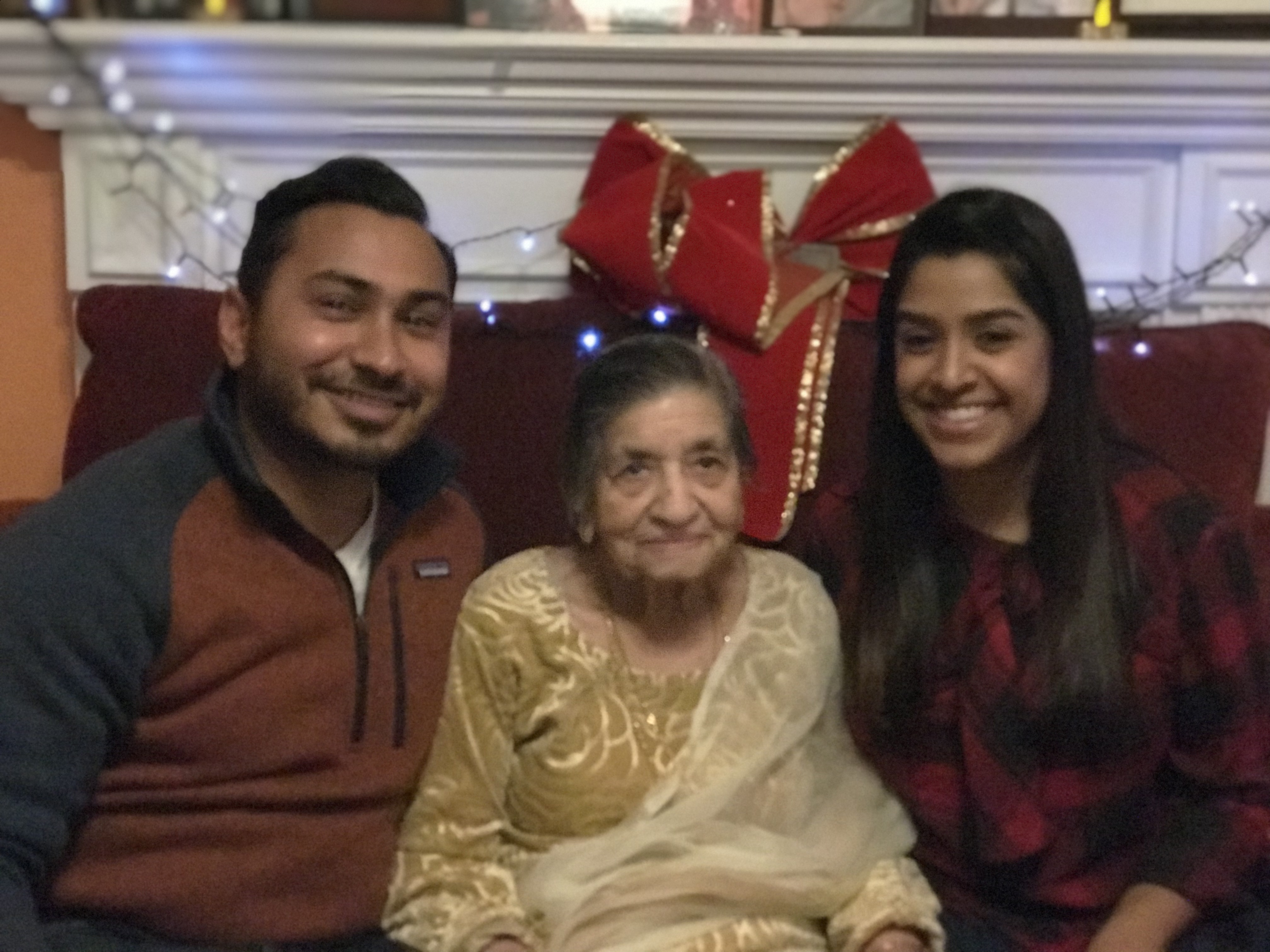

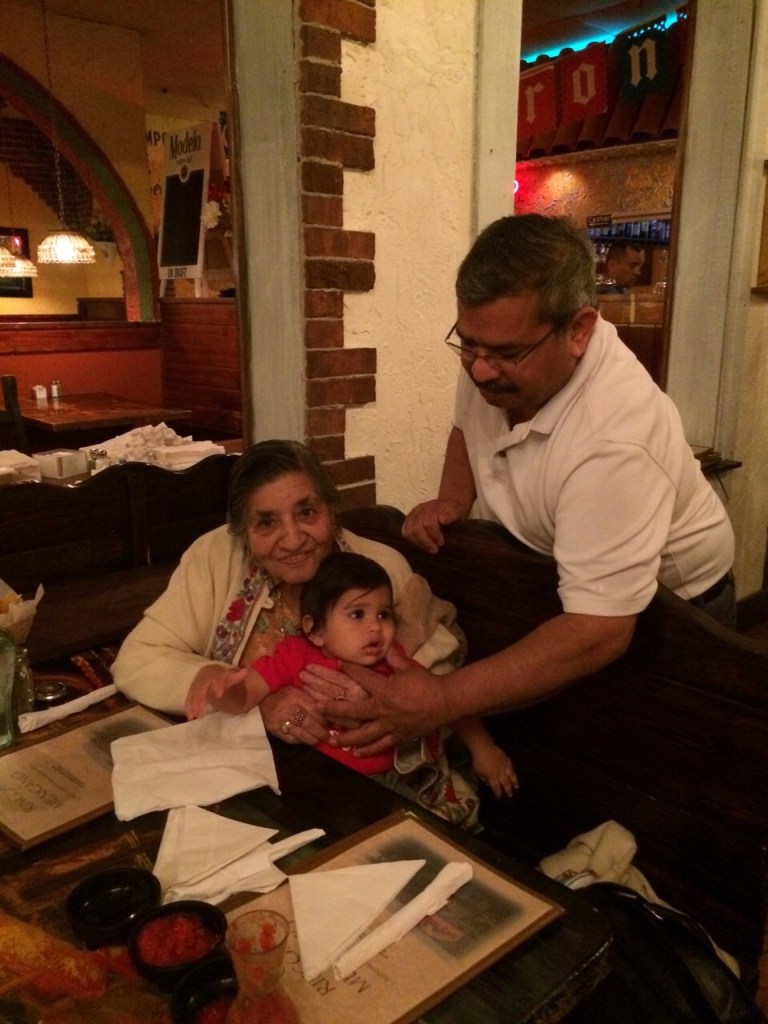

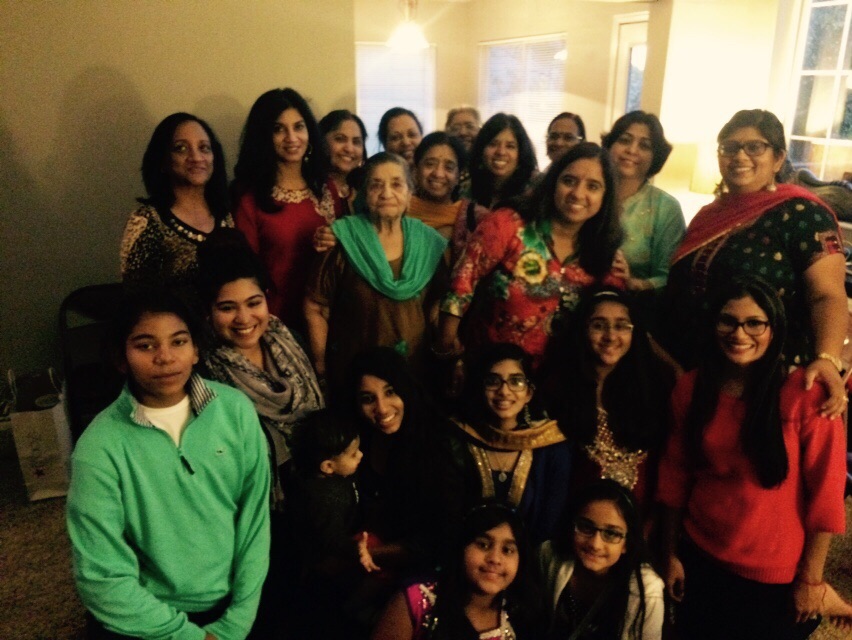

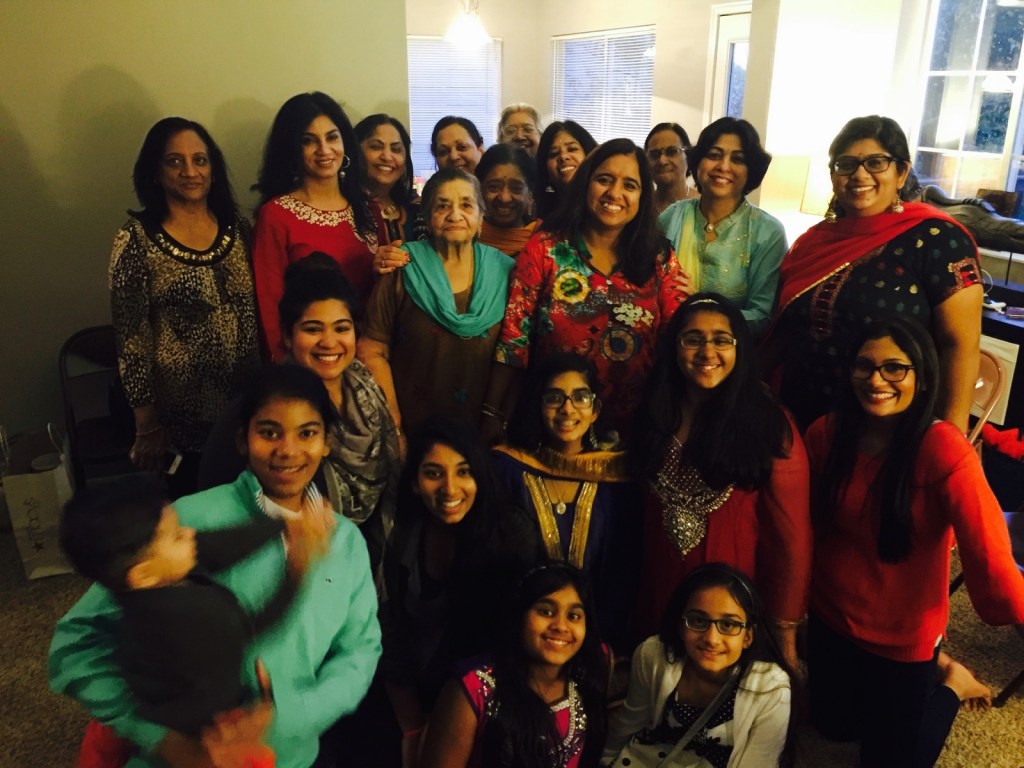

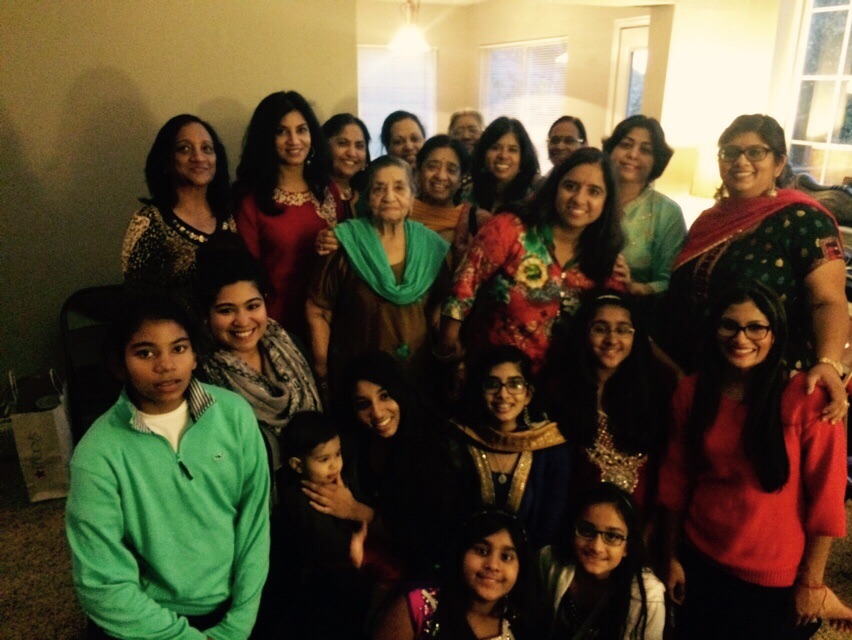

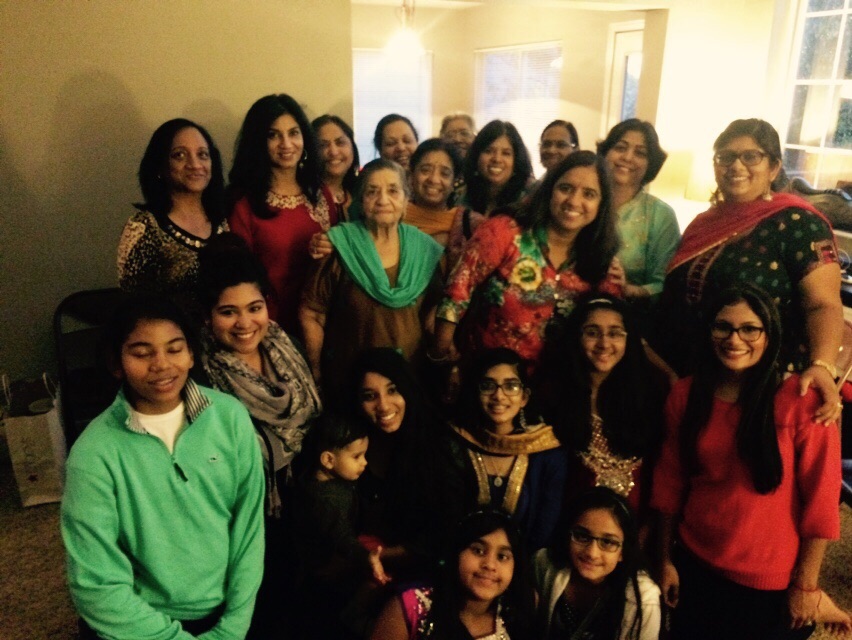

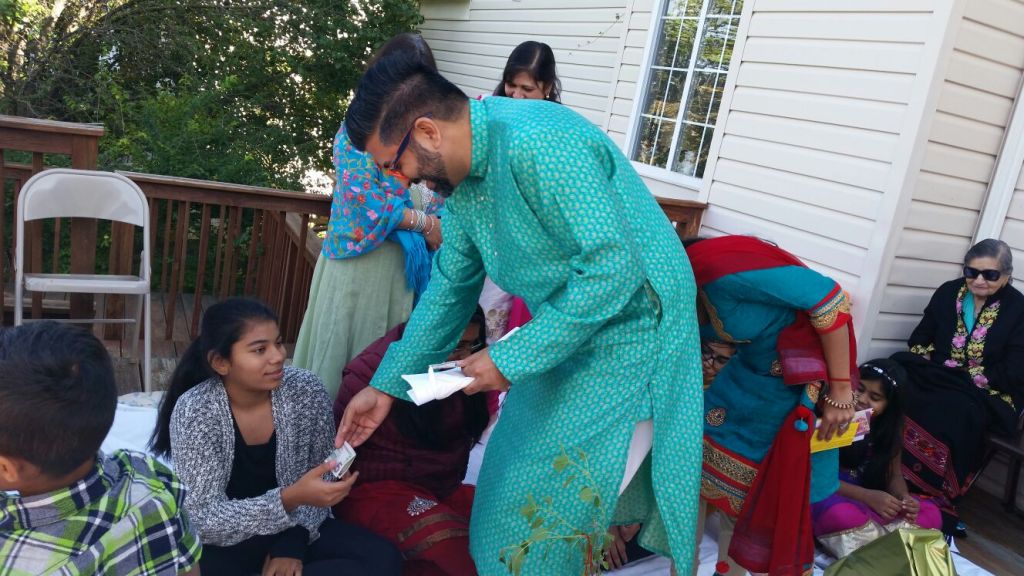

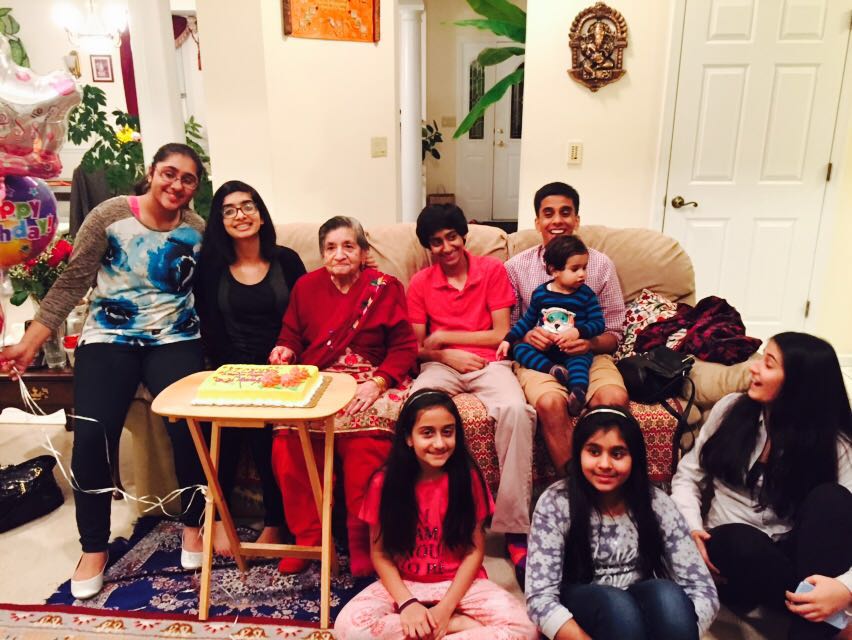

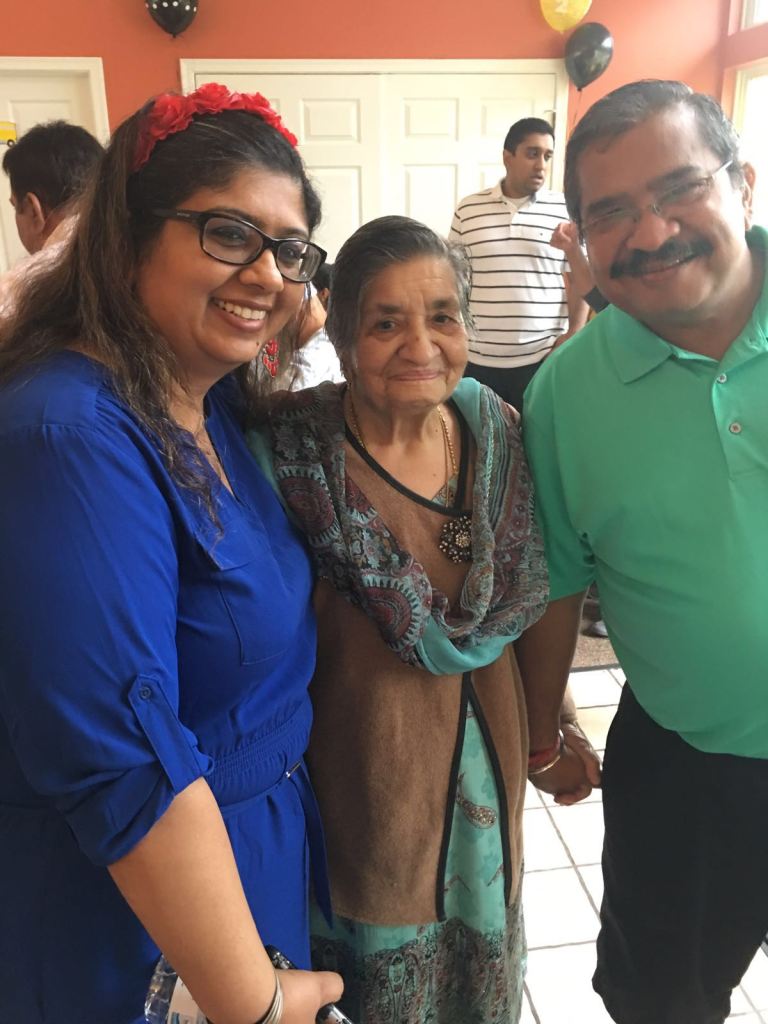

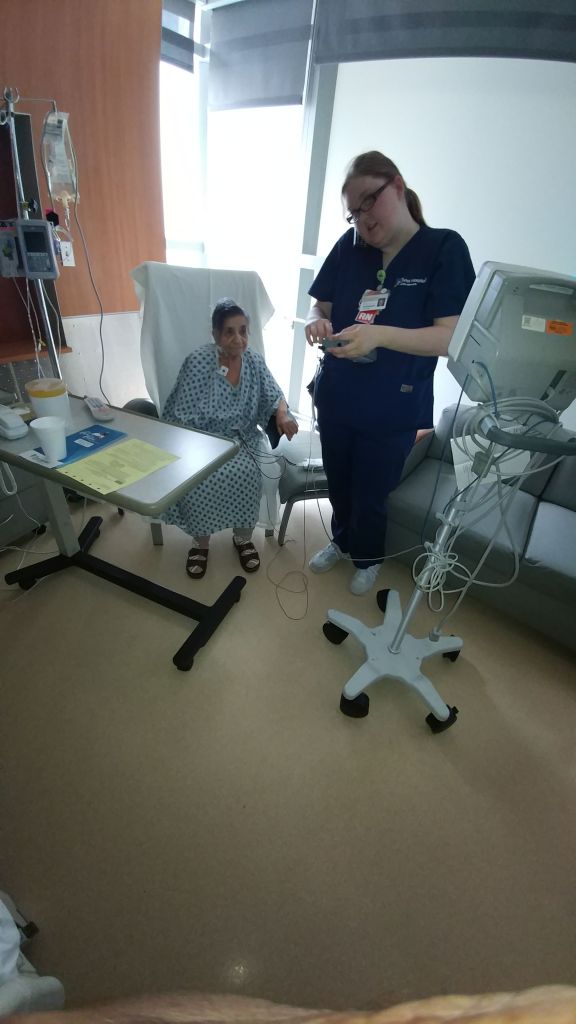

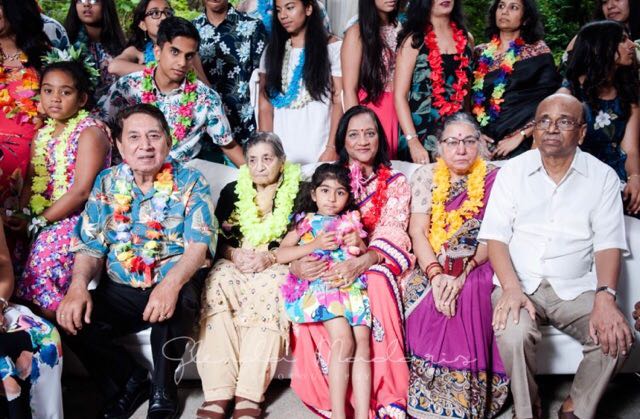

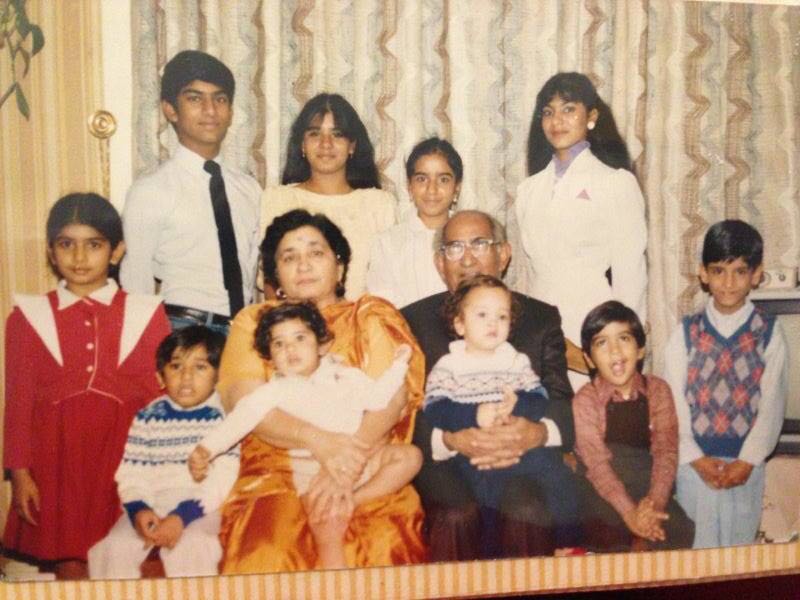

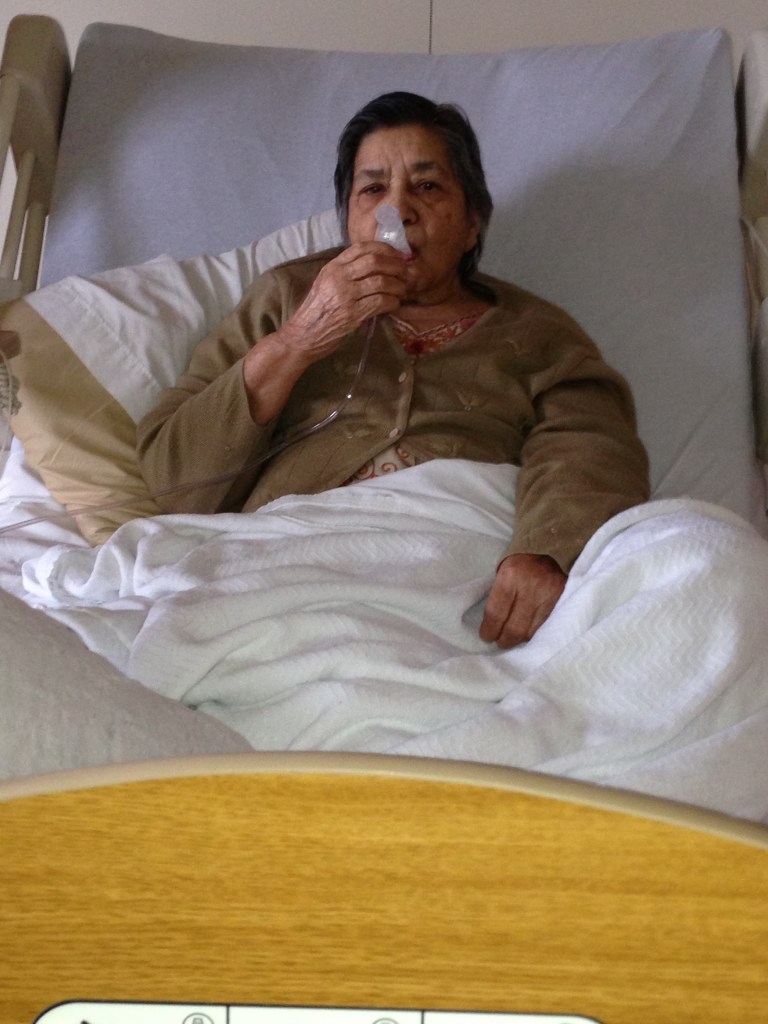

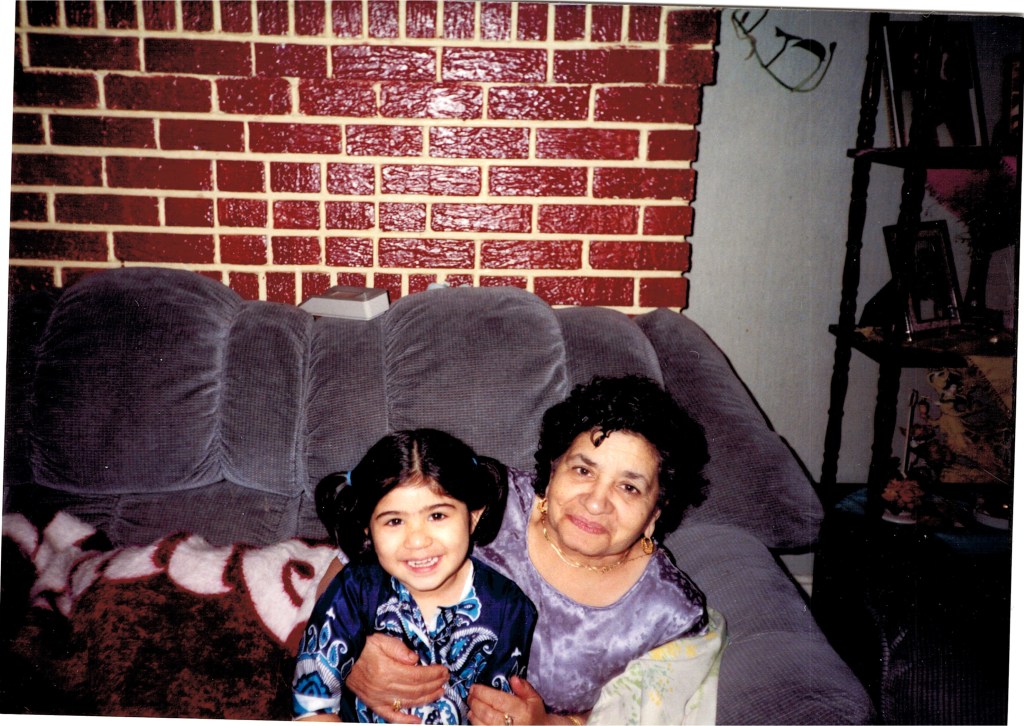

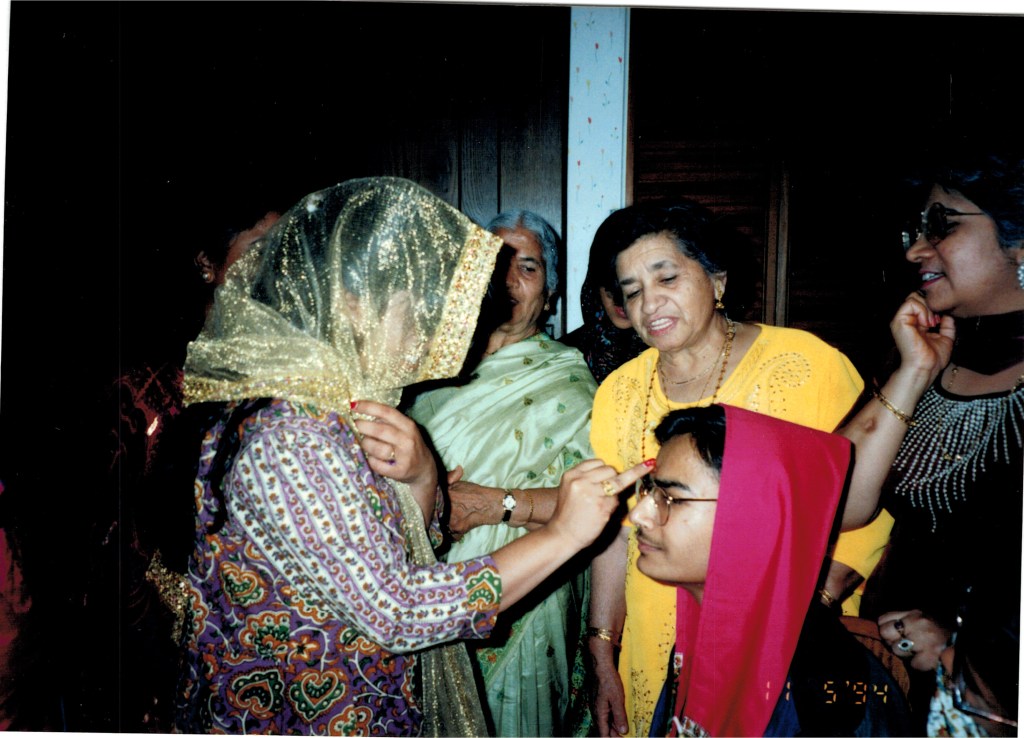

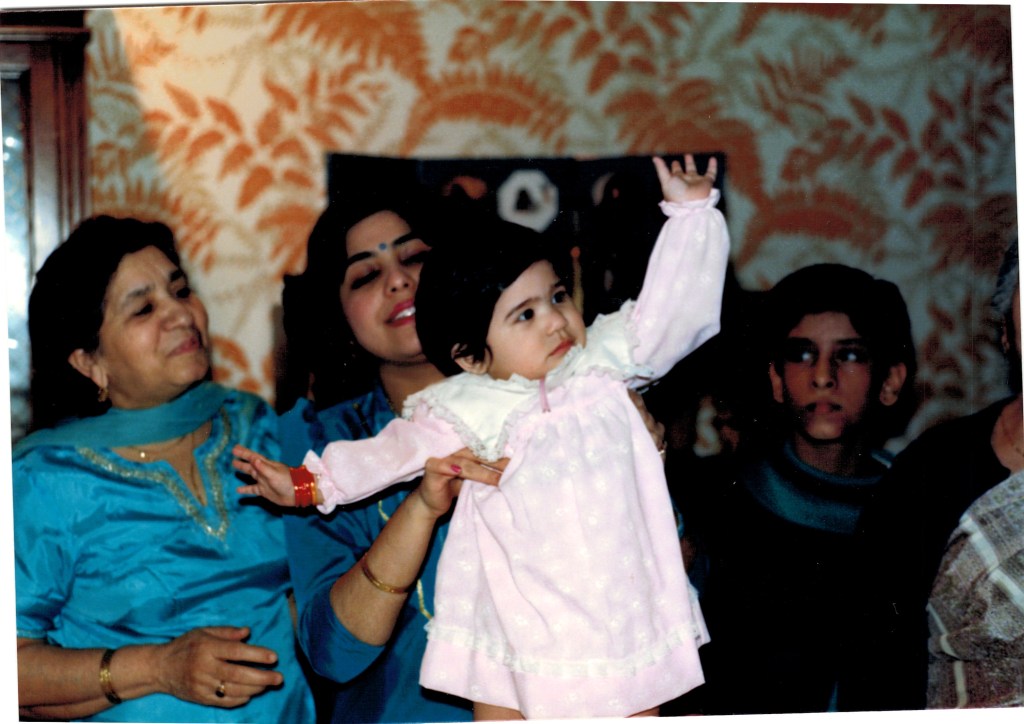

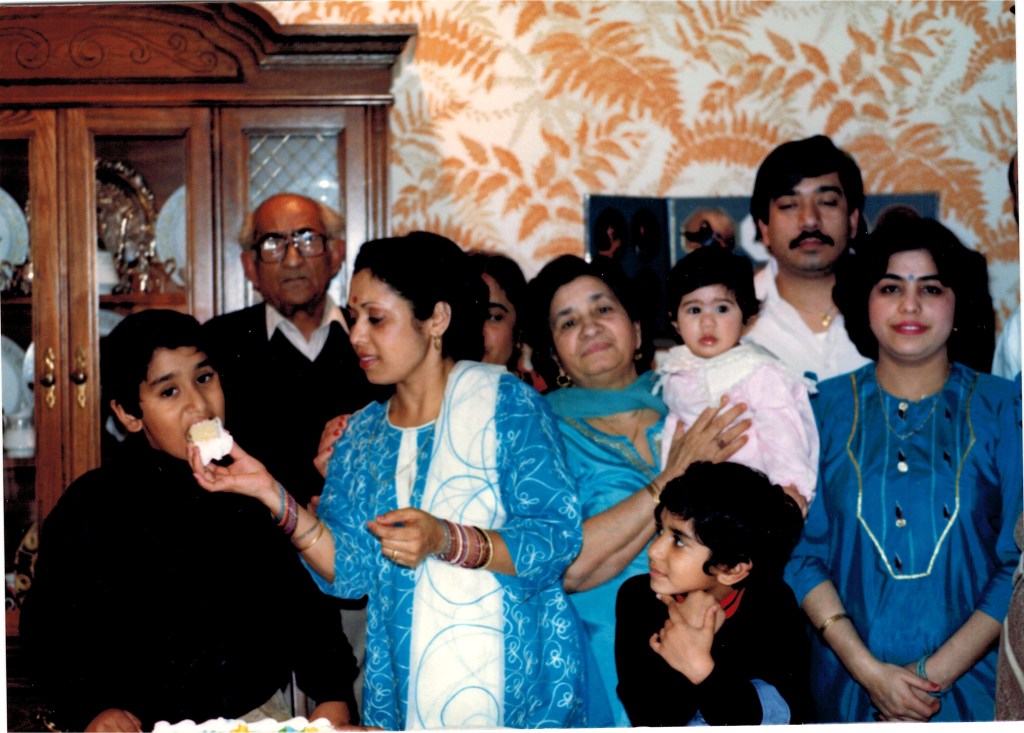

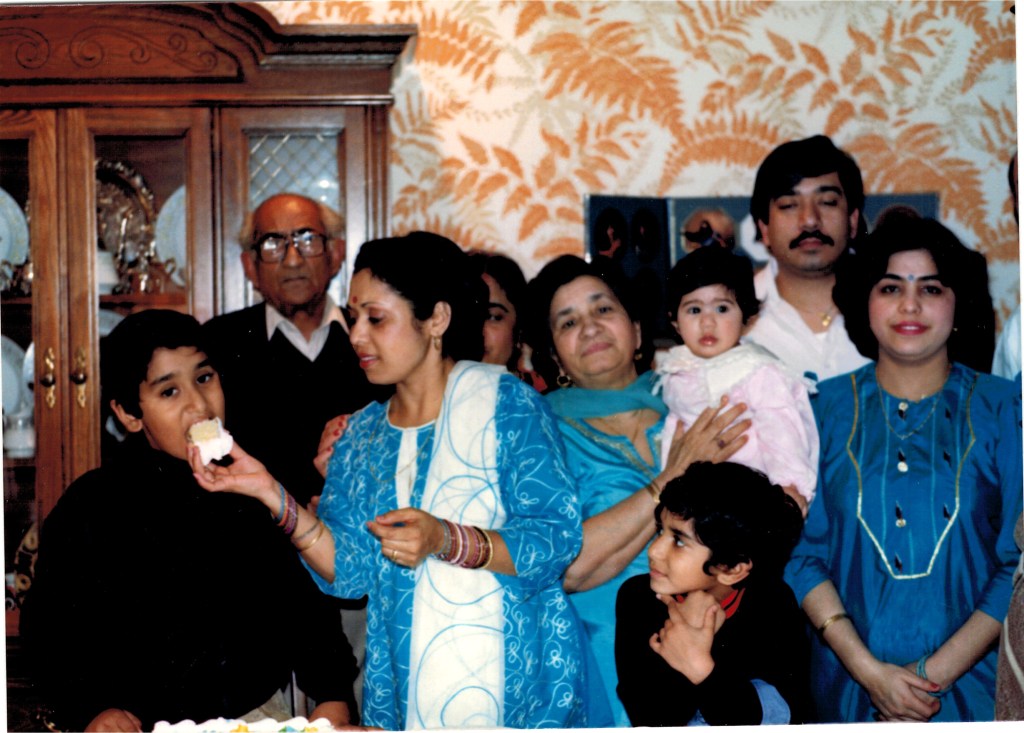

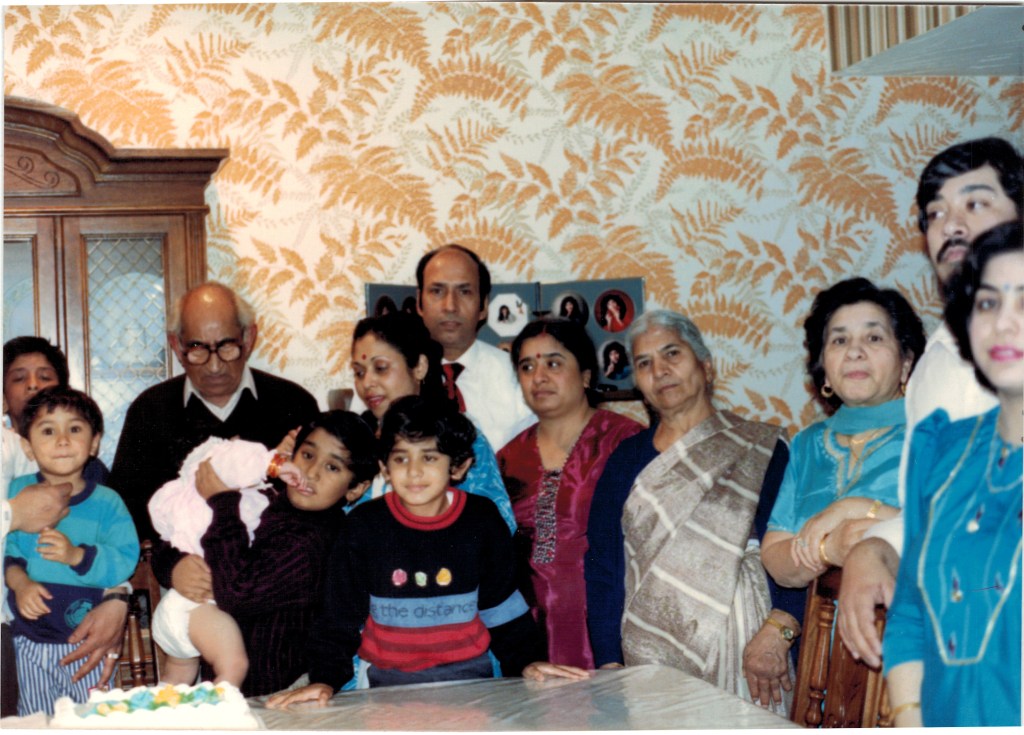

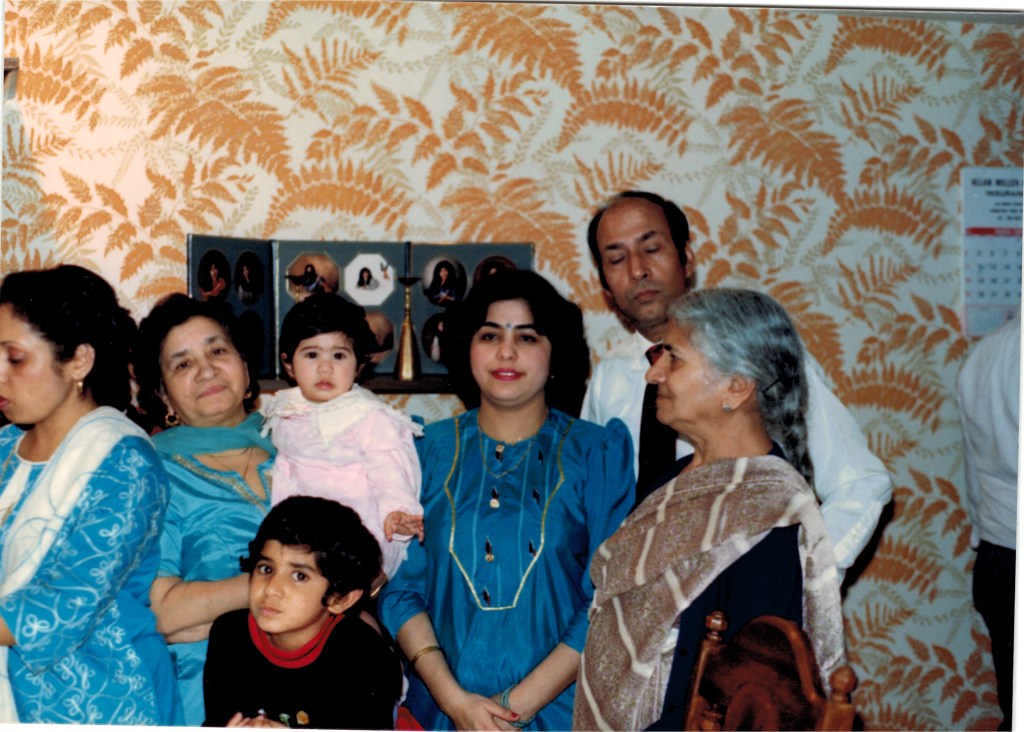

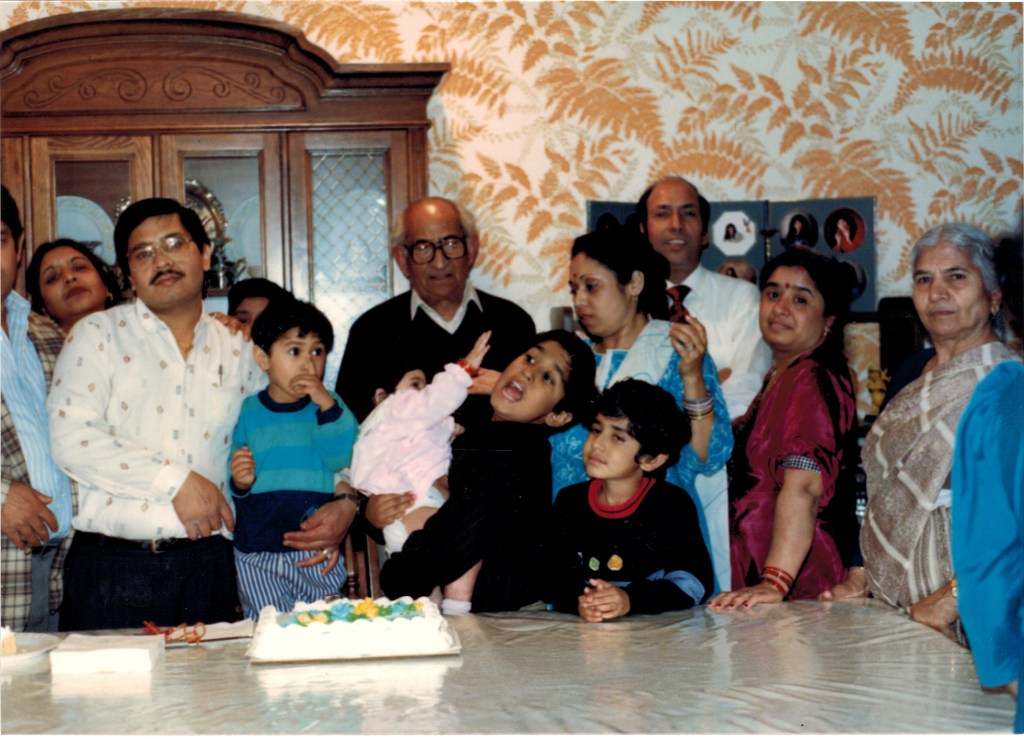

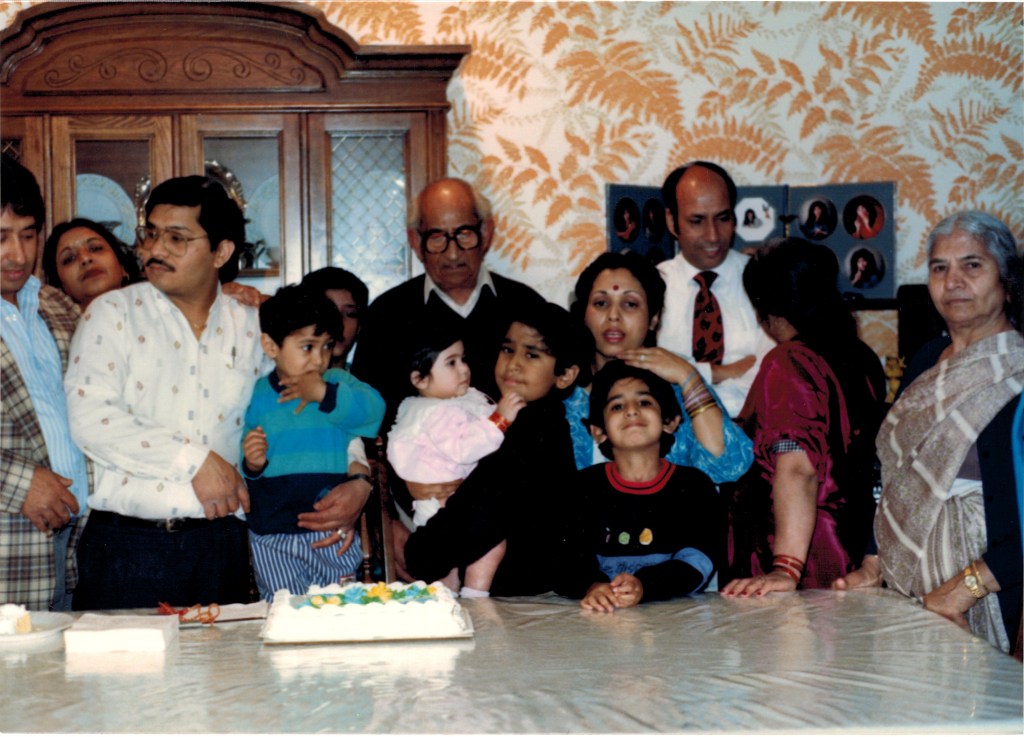

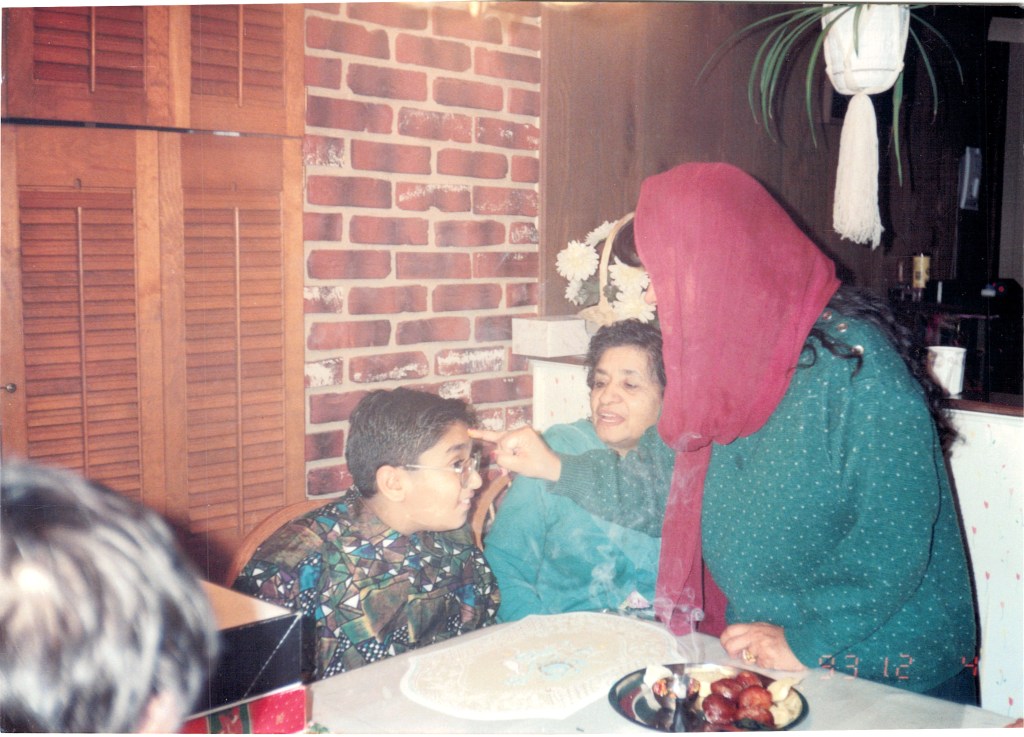

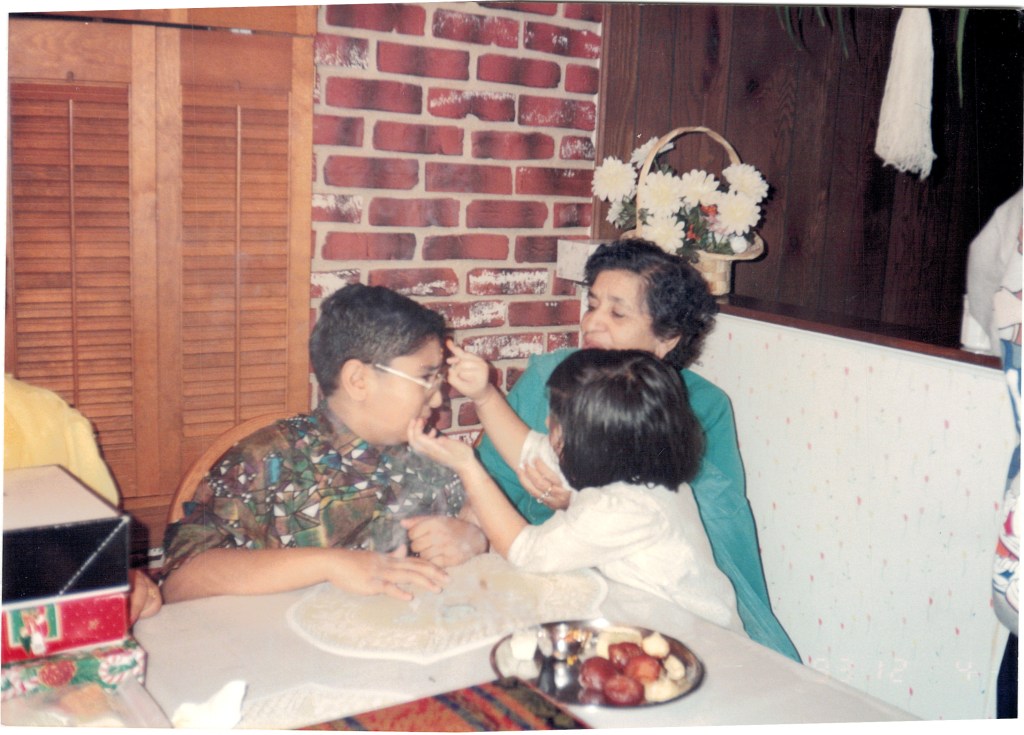

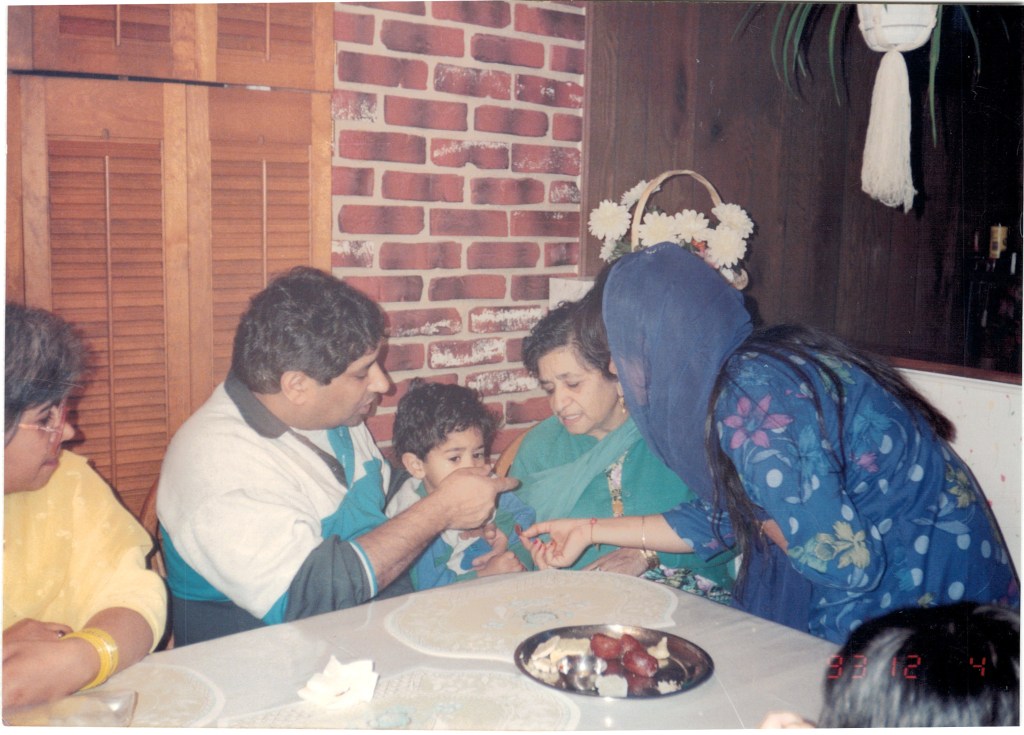

Madhu didi

-

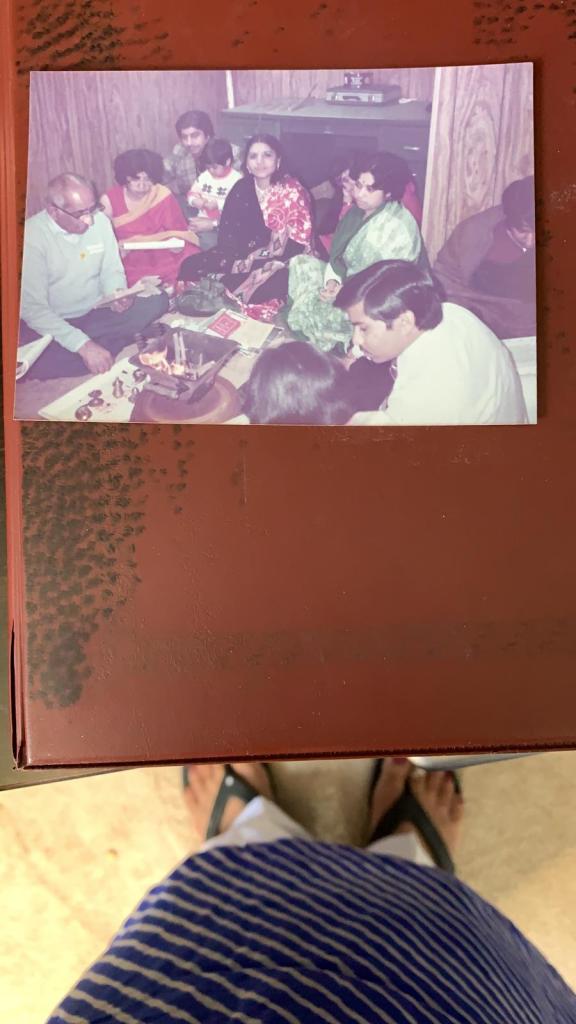

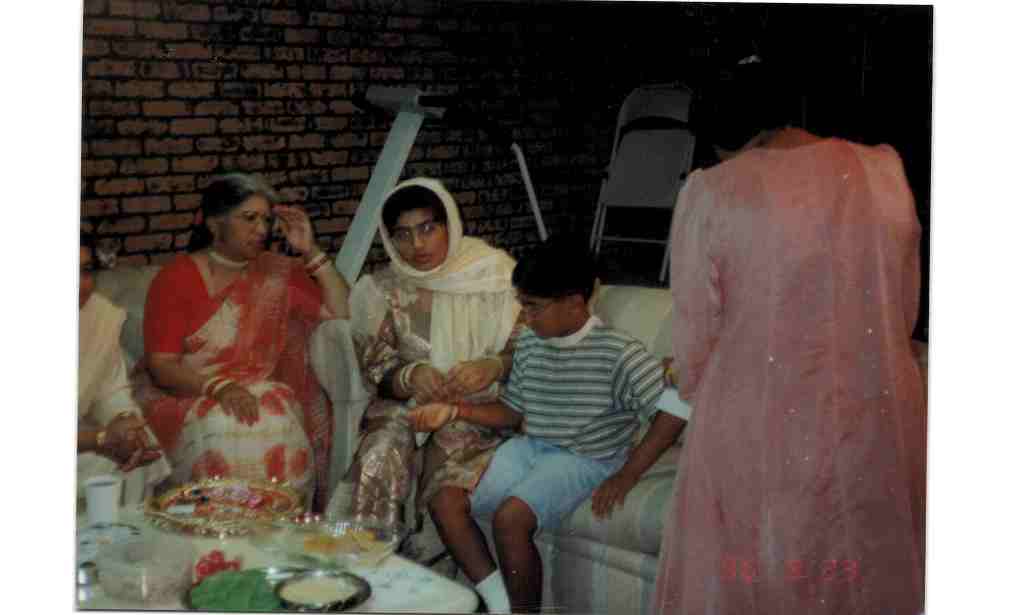

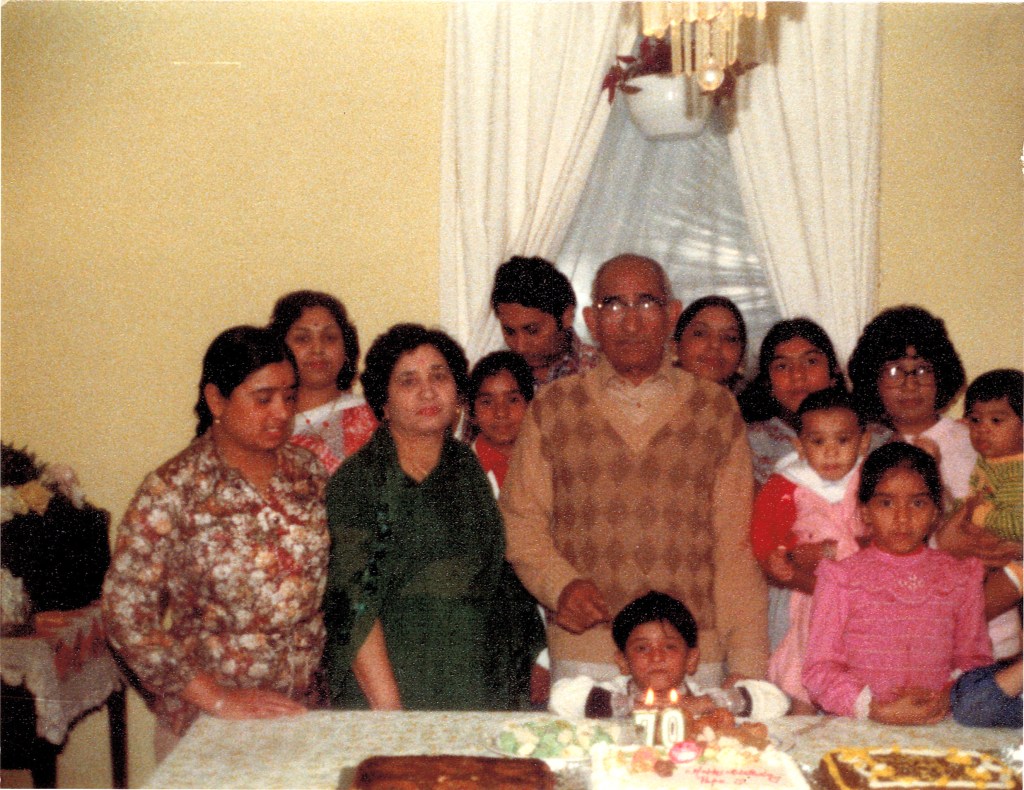

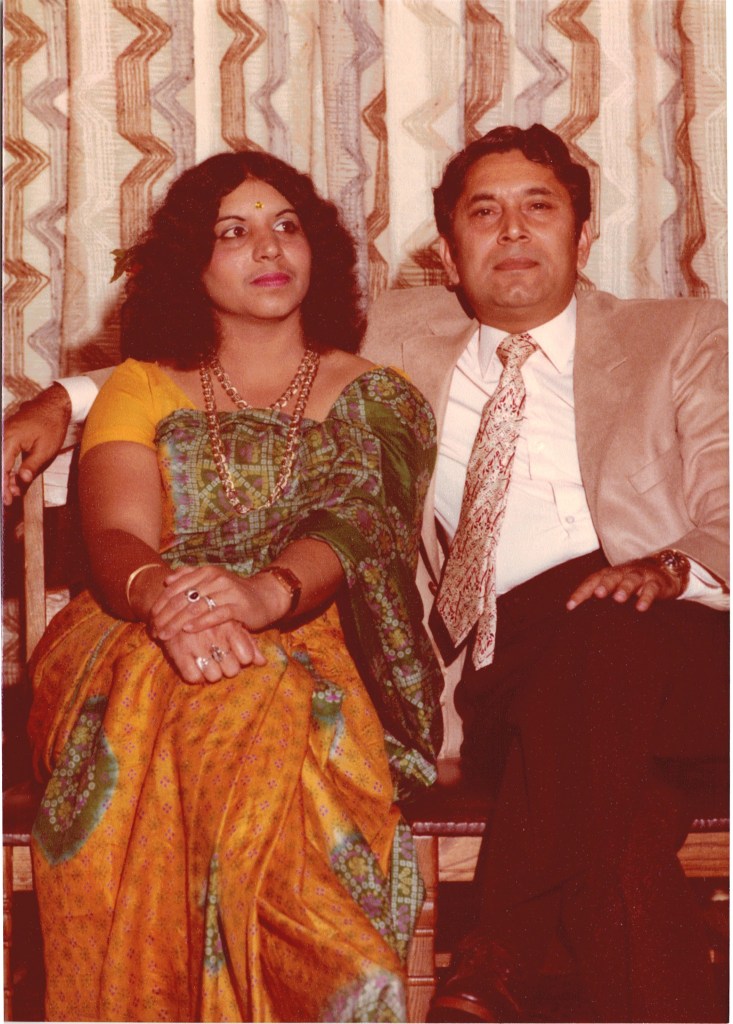

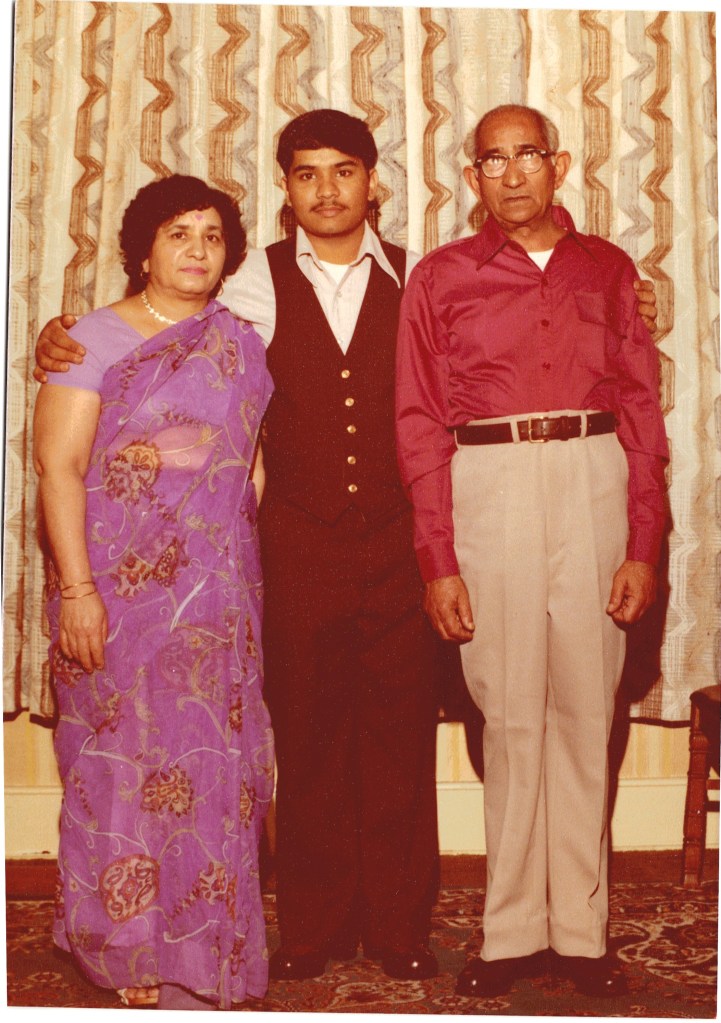

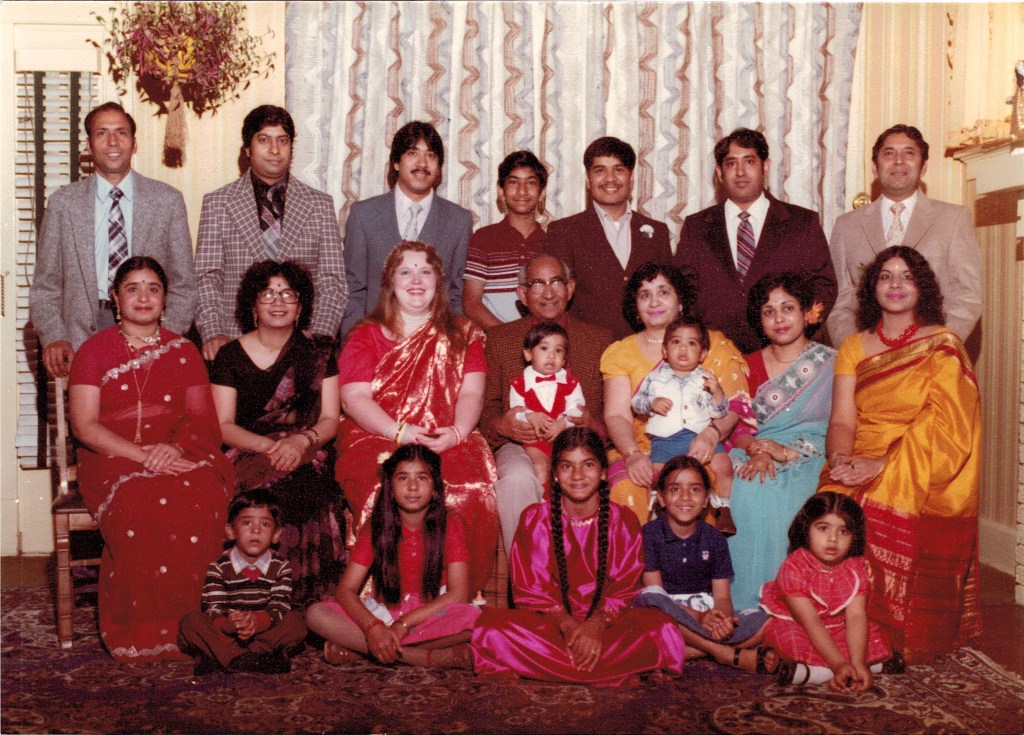

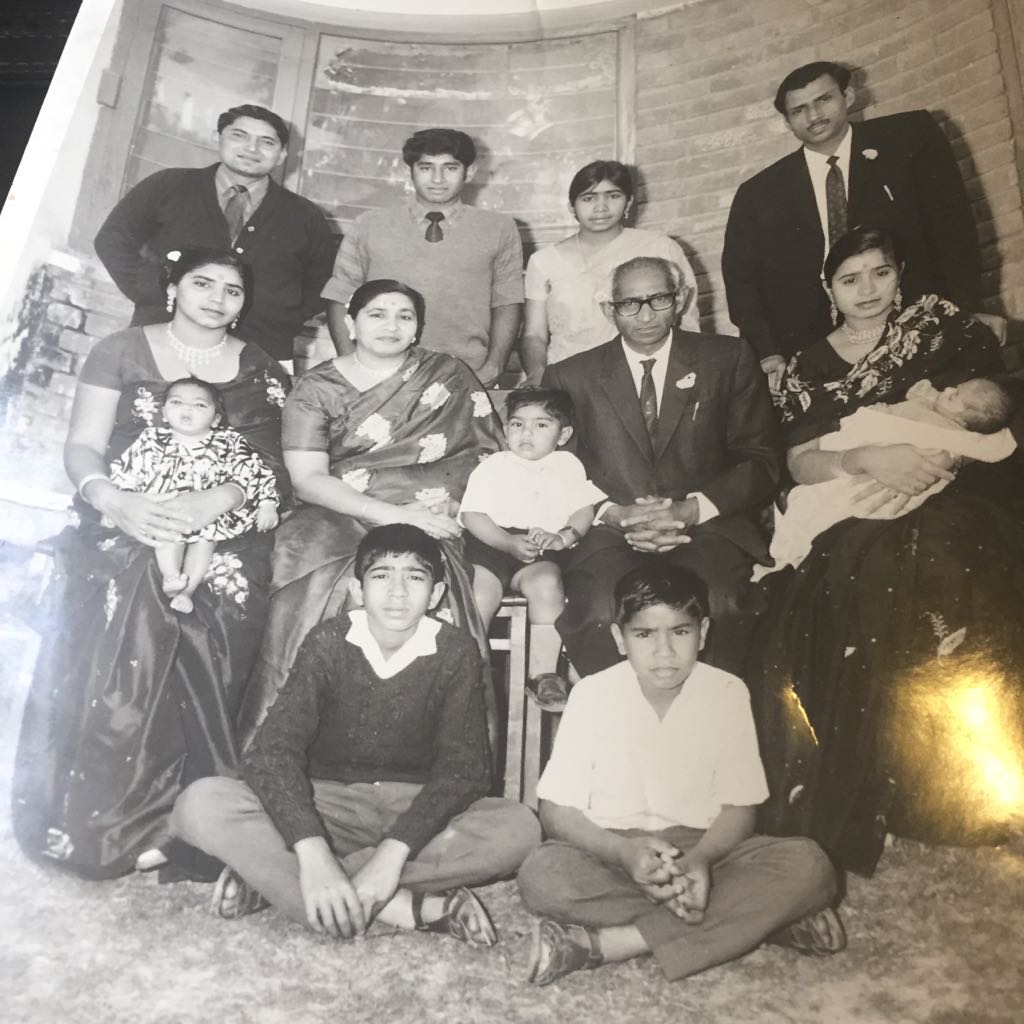

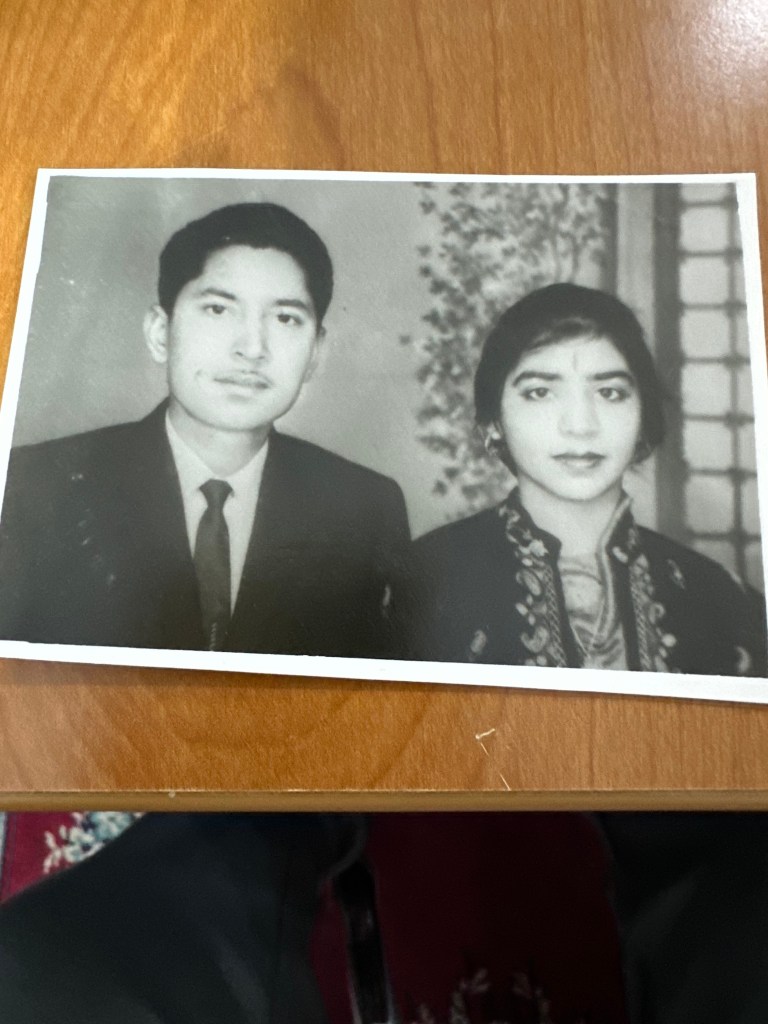

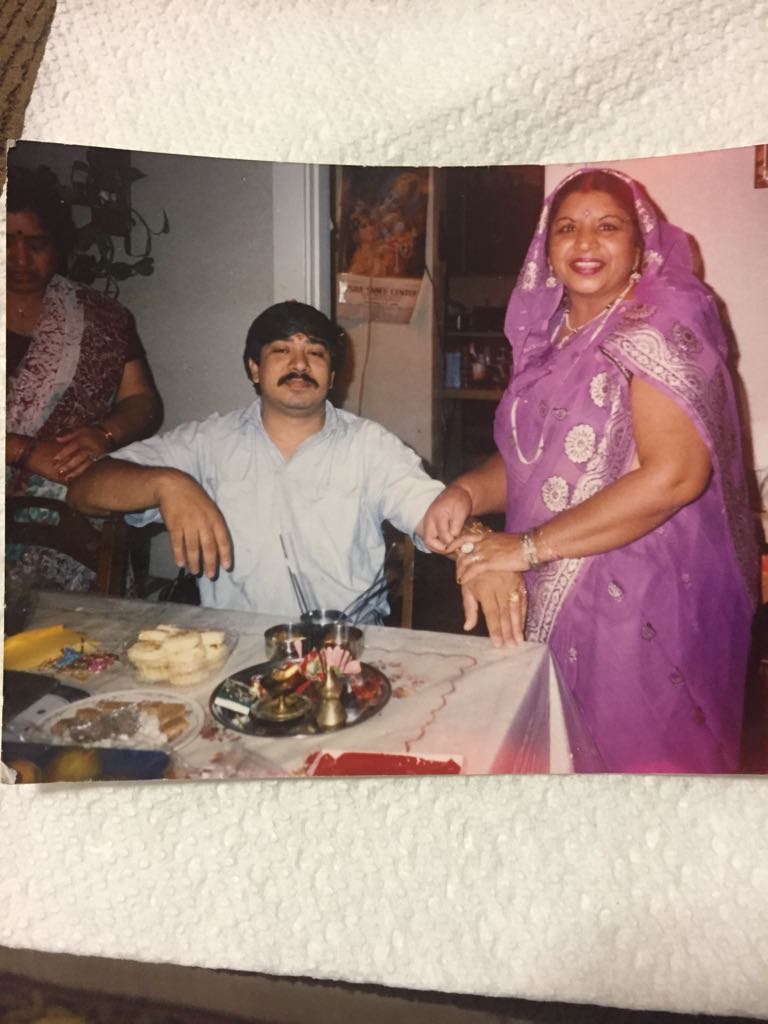

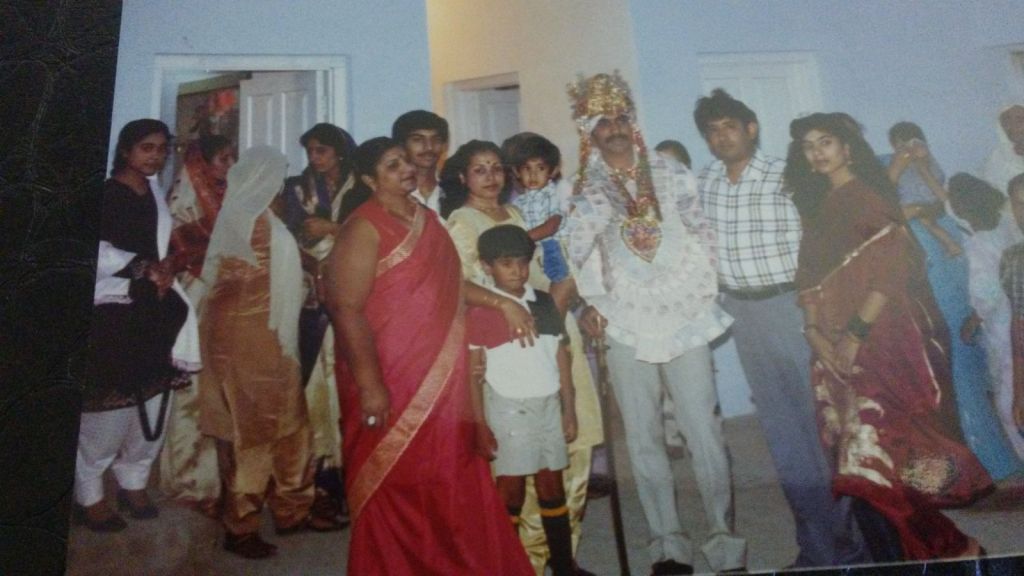

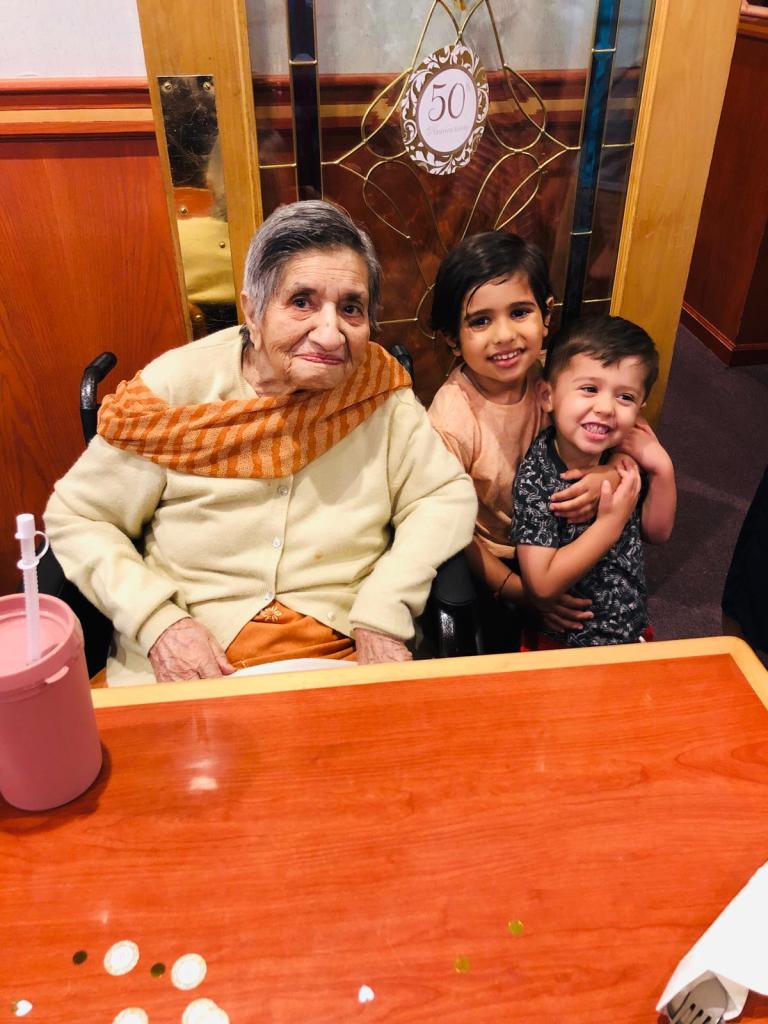

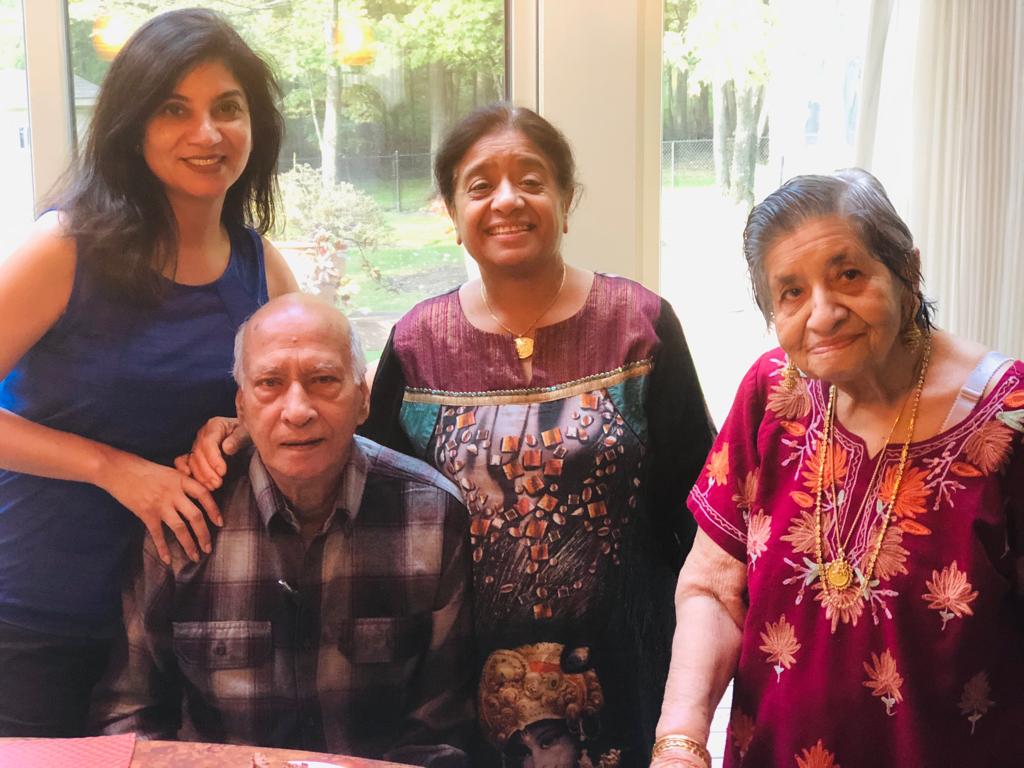

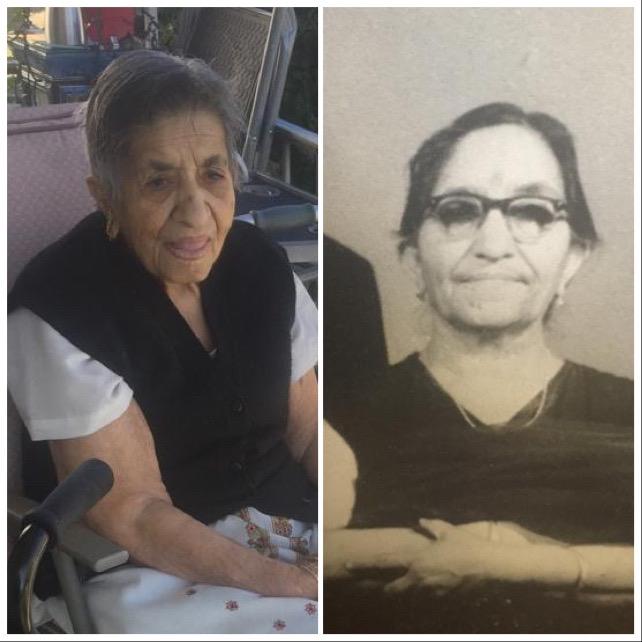

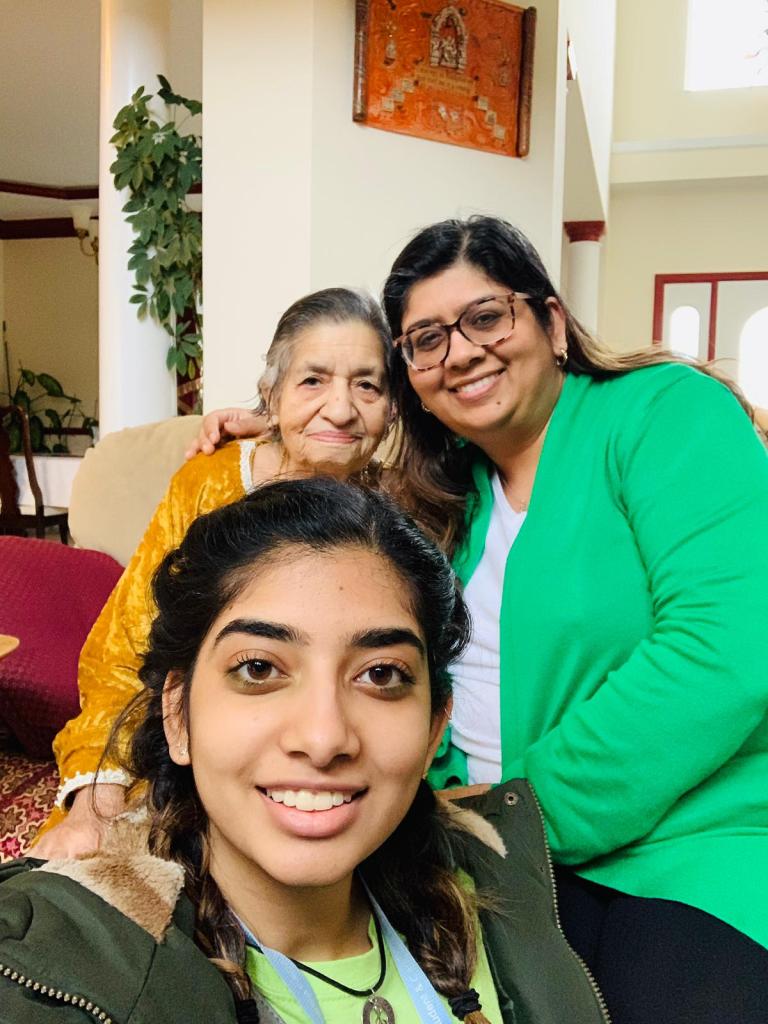

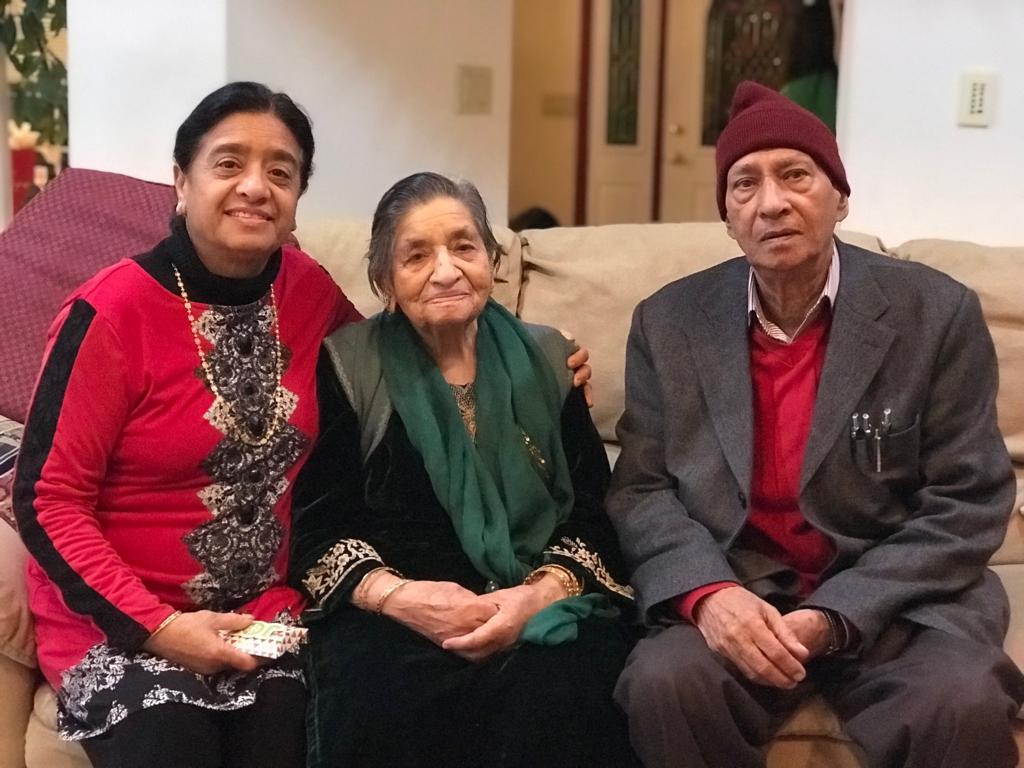

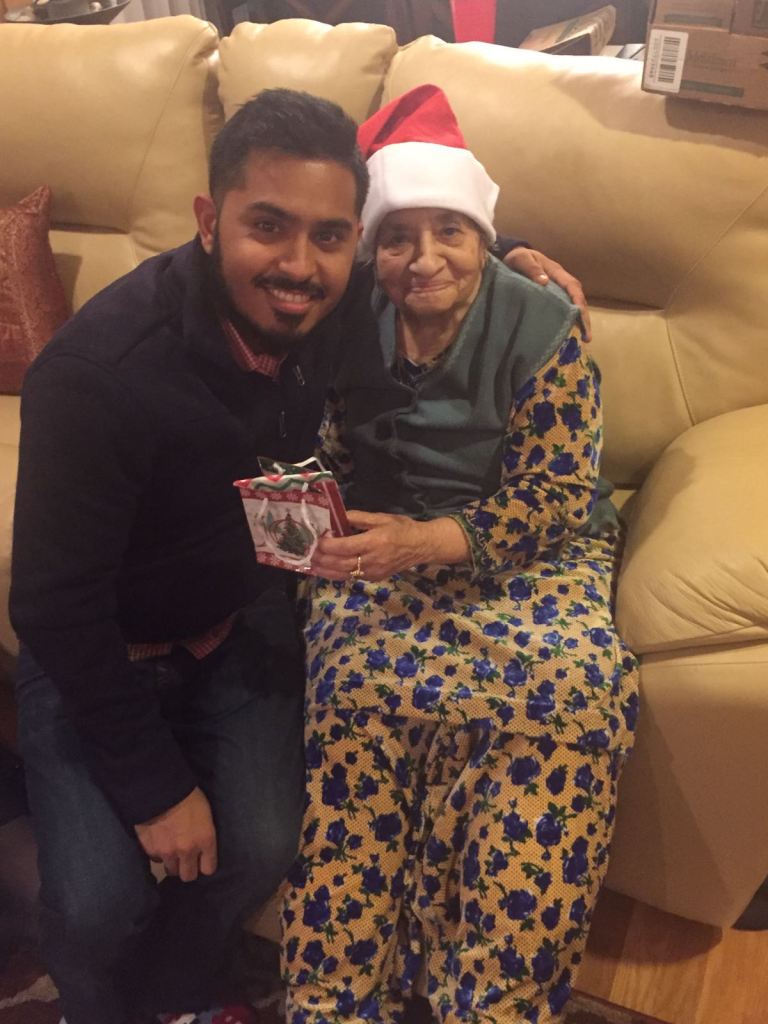

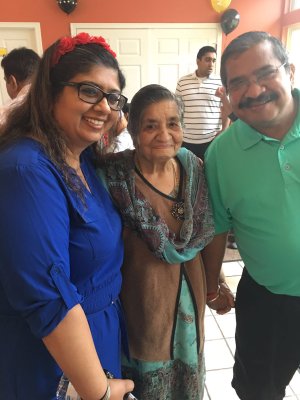

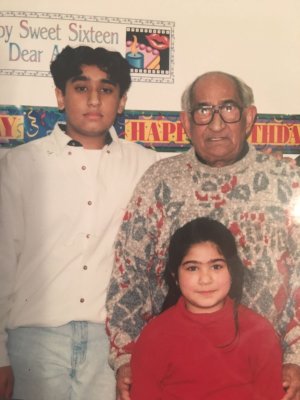

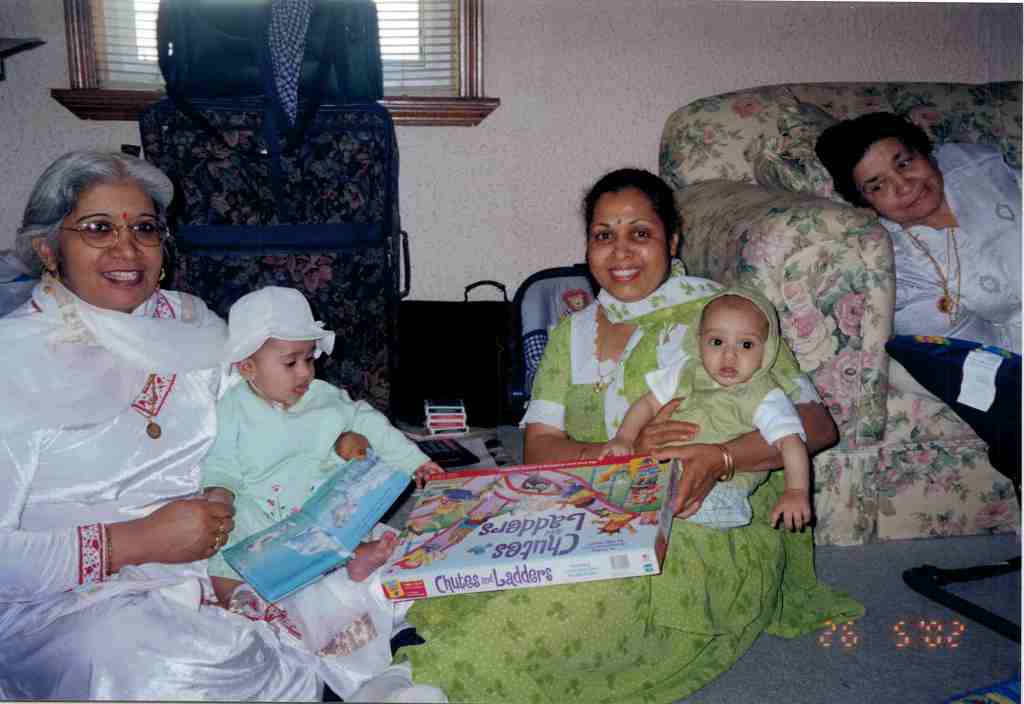

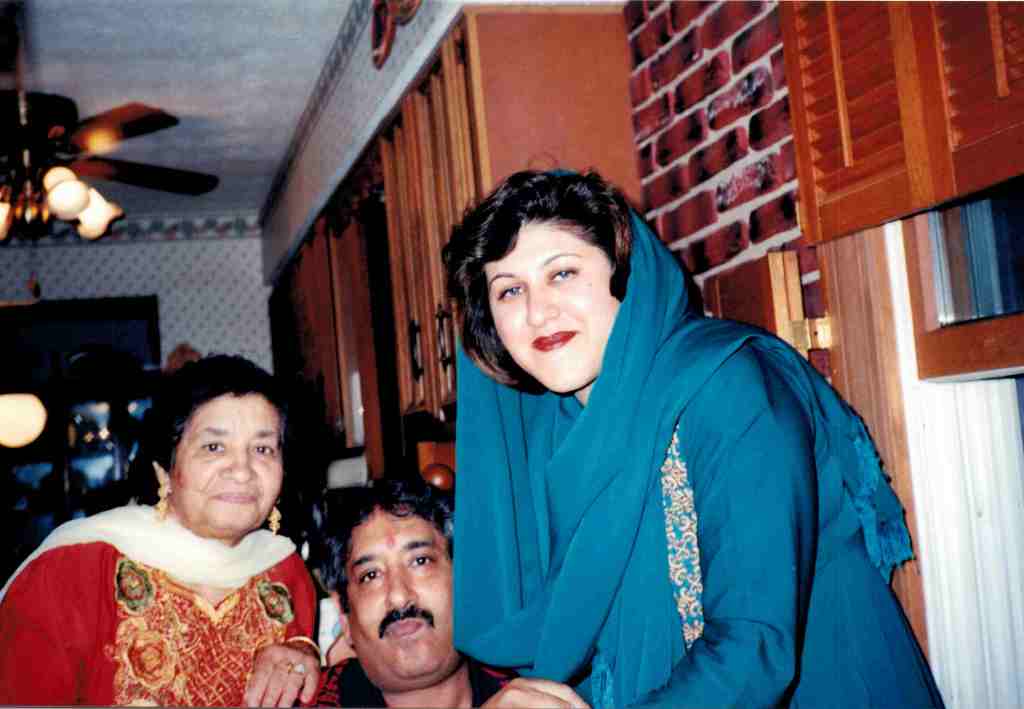

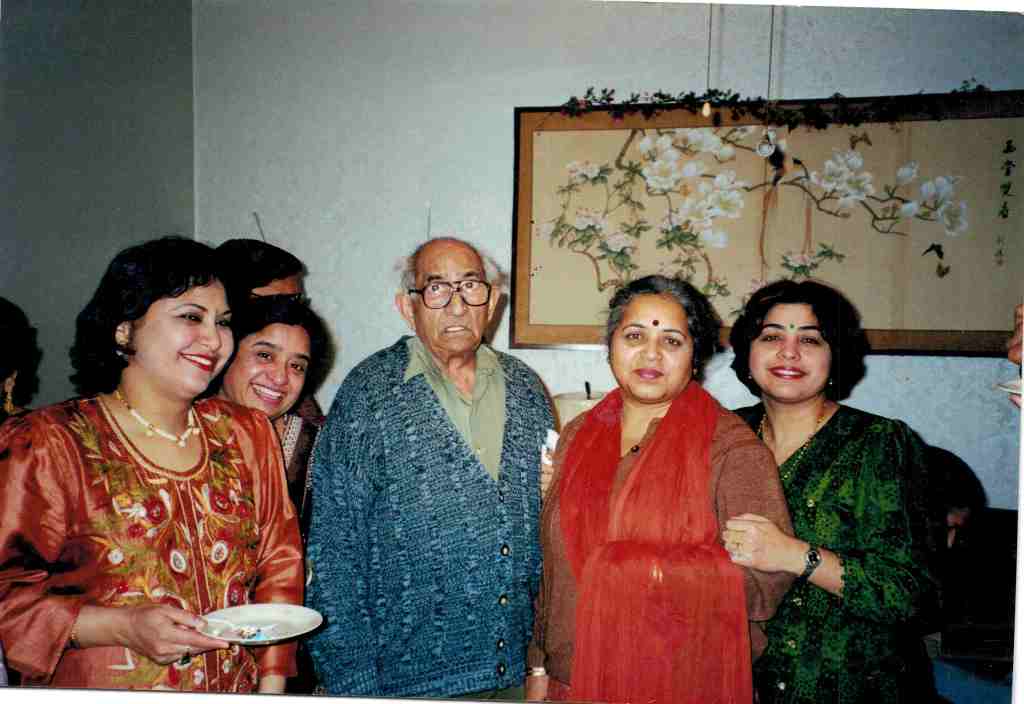

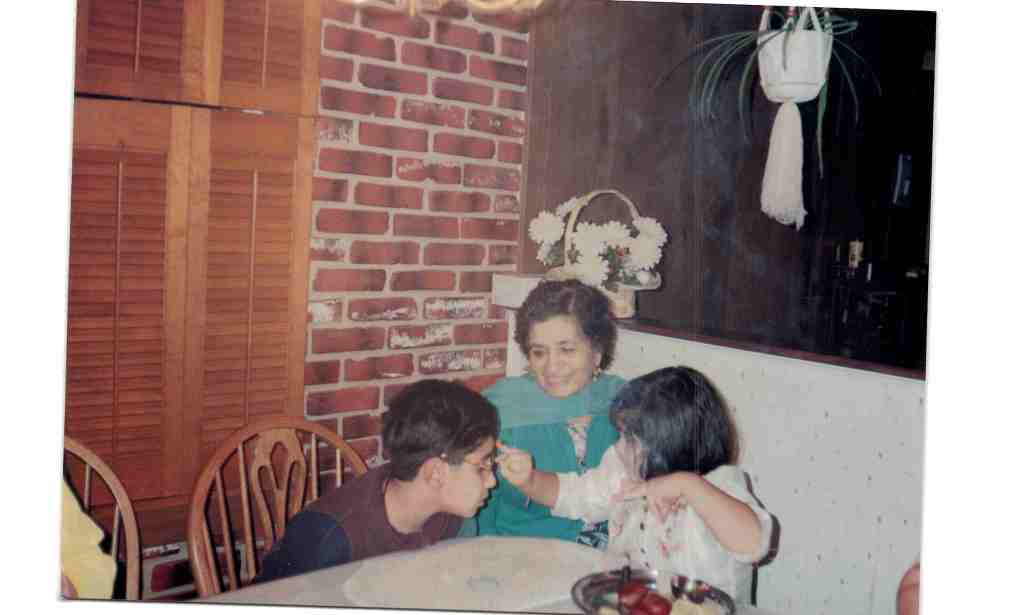

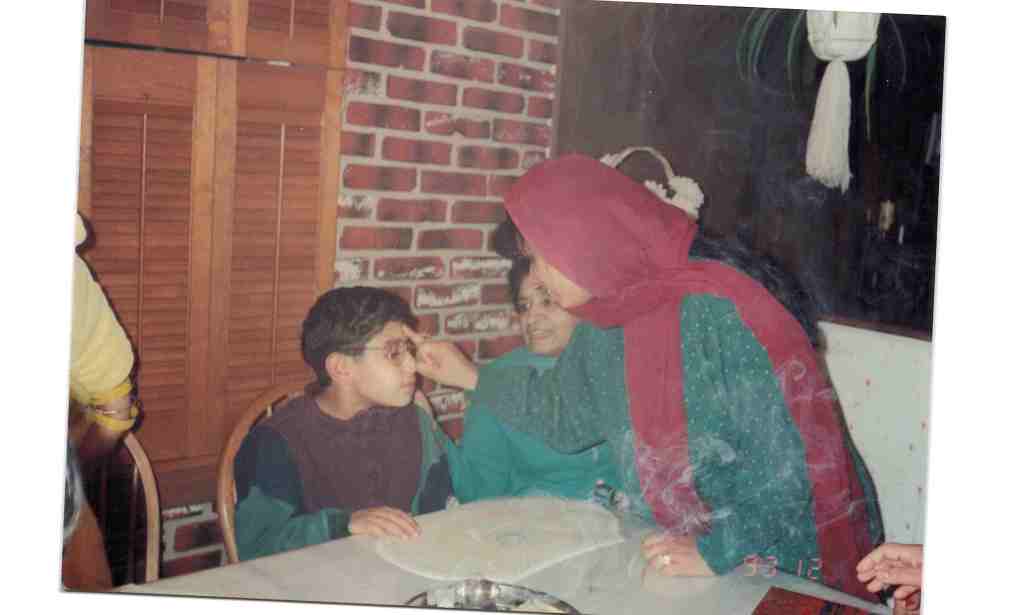

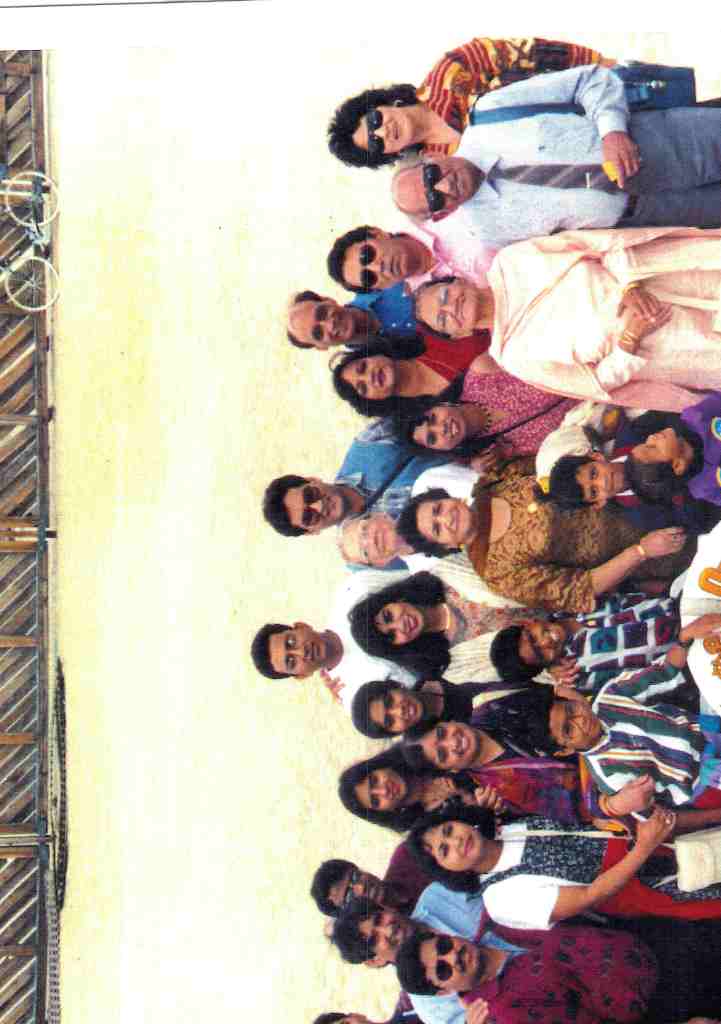

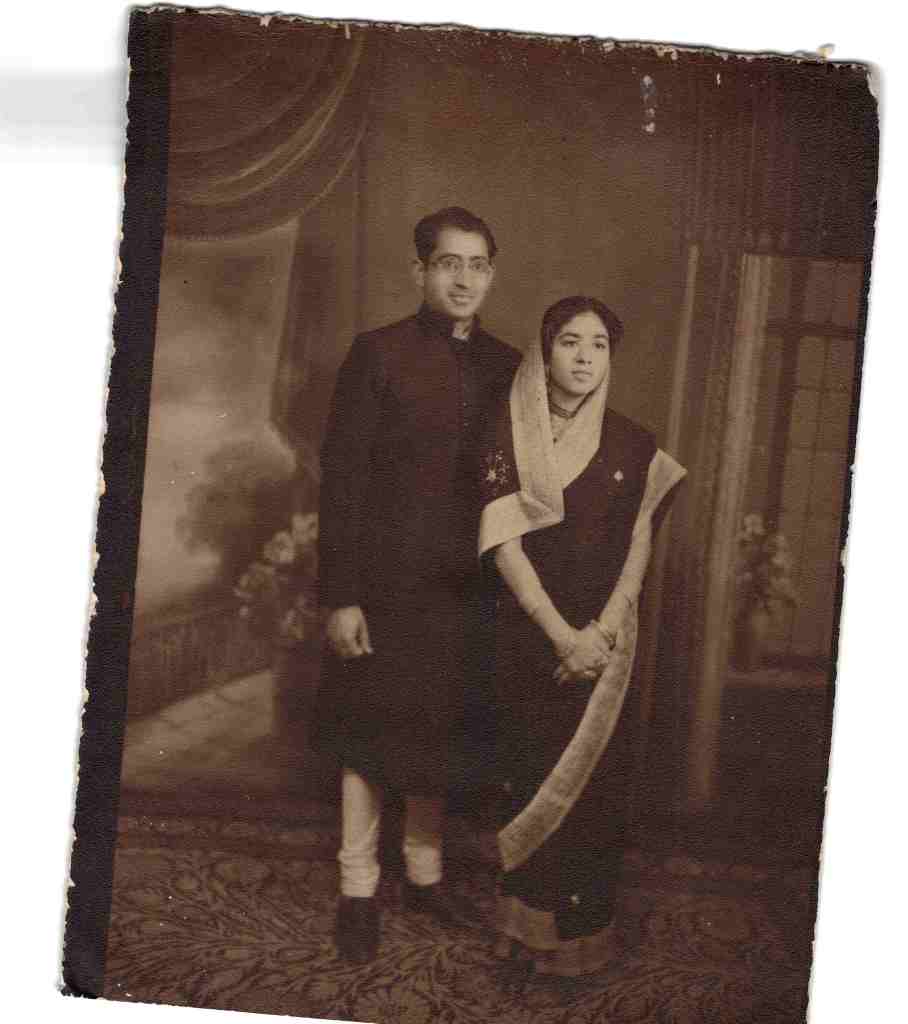

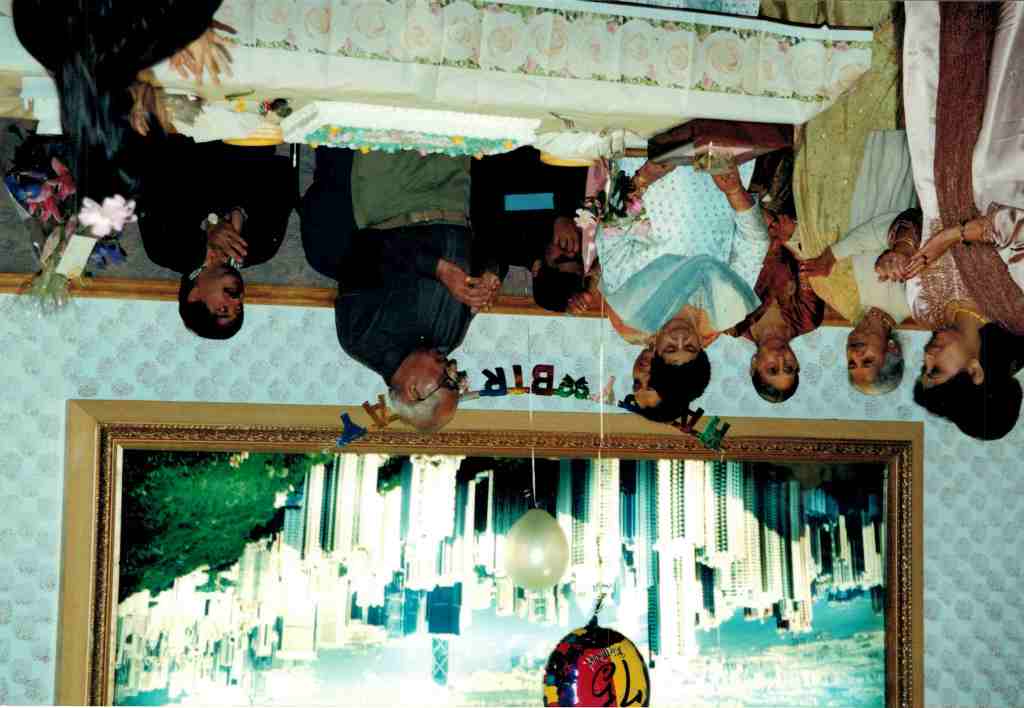

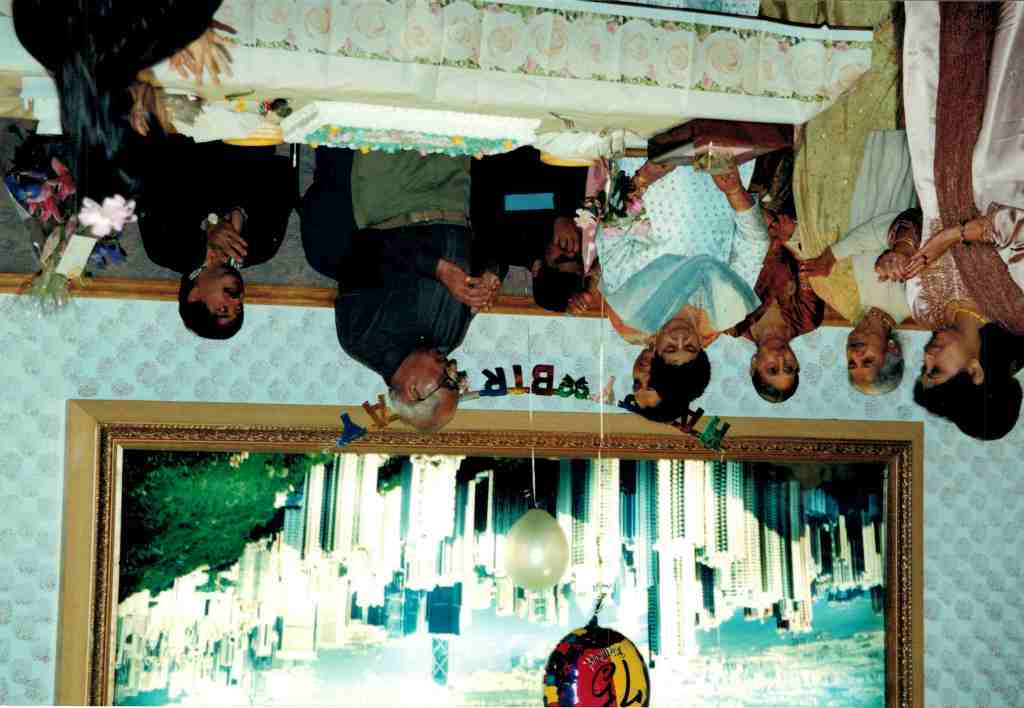

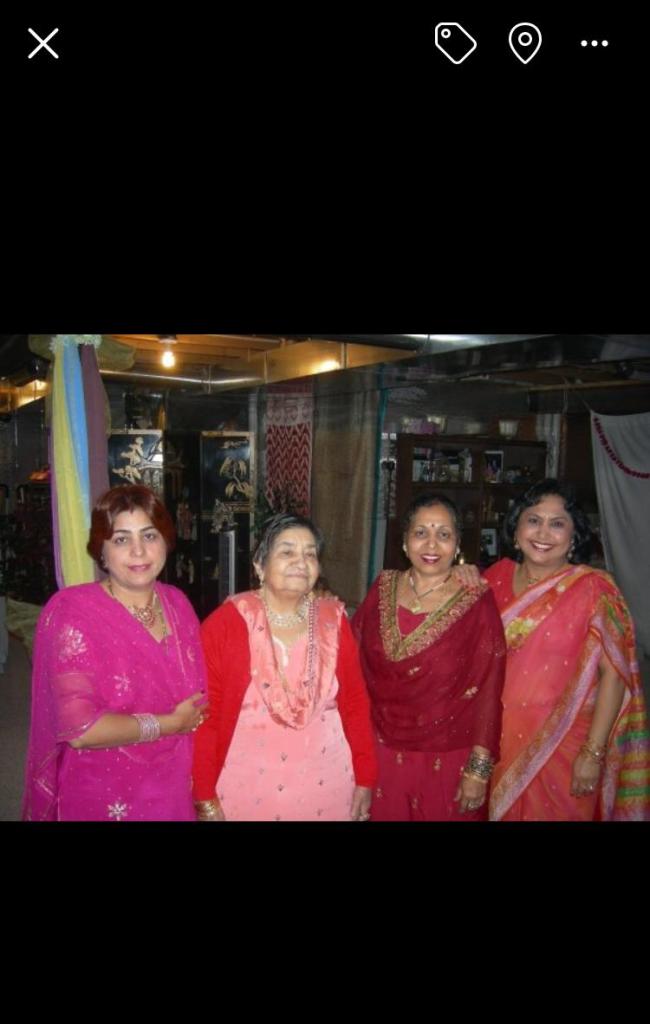

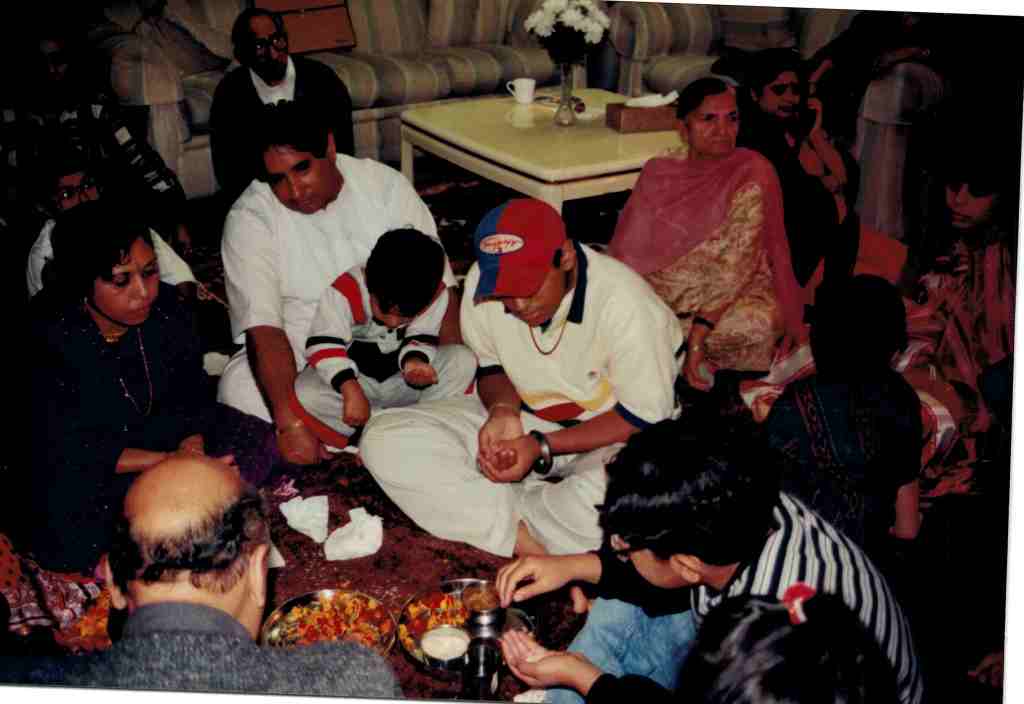

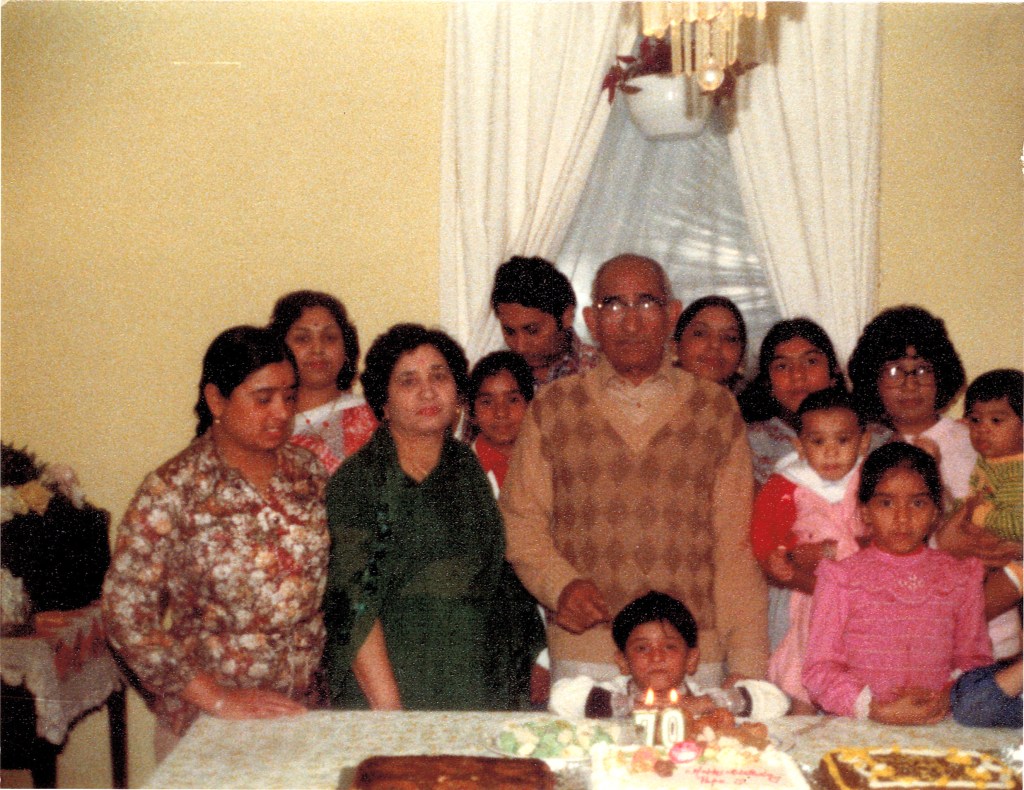

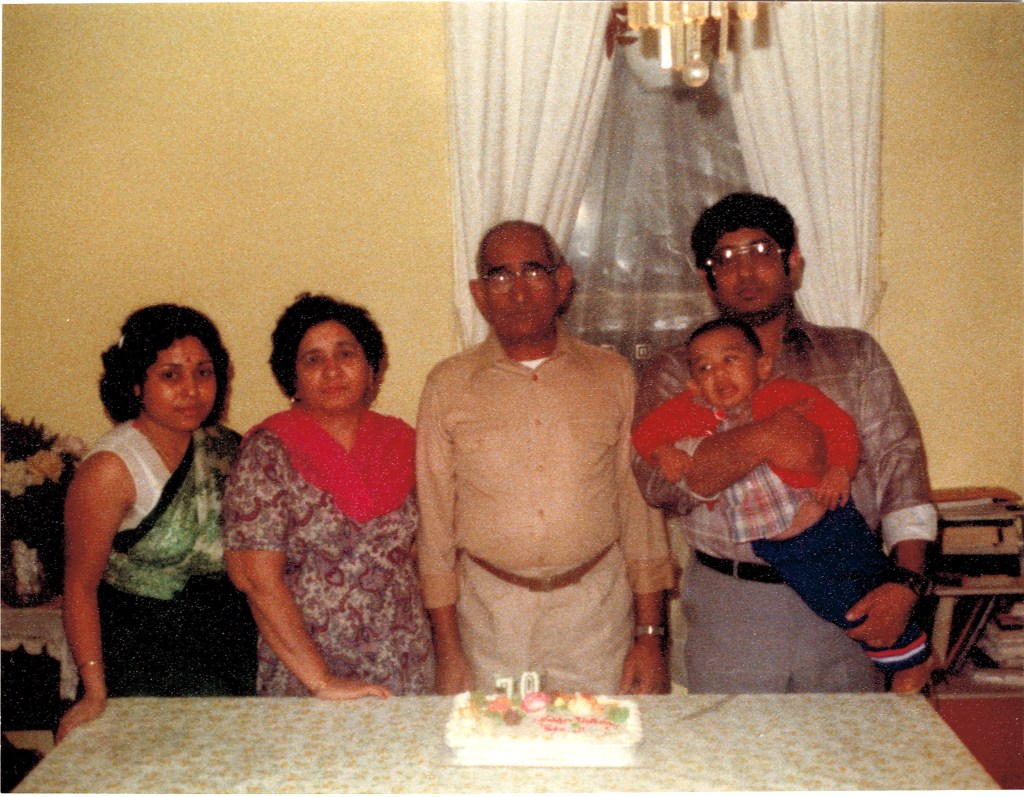

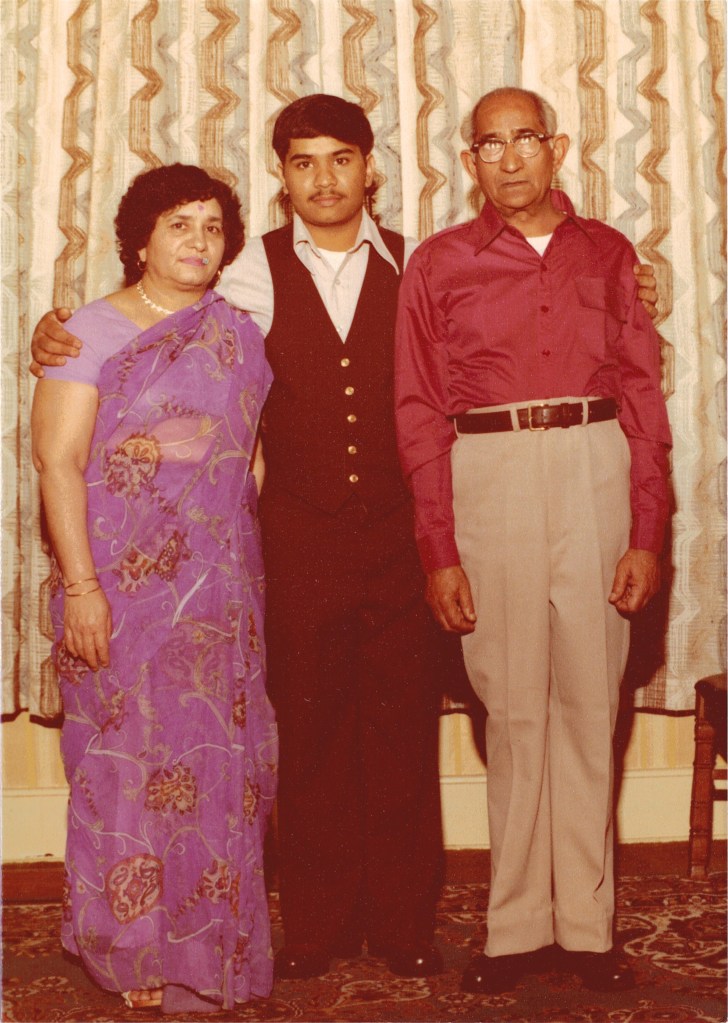

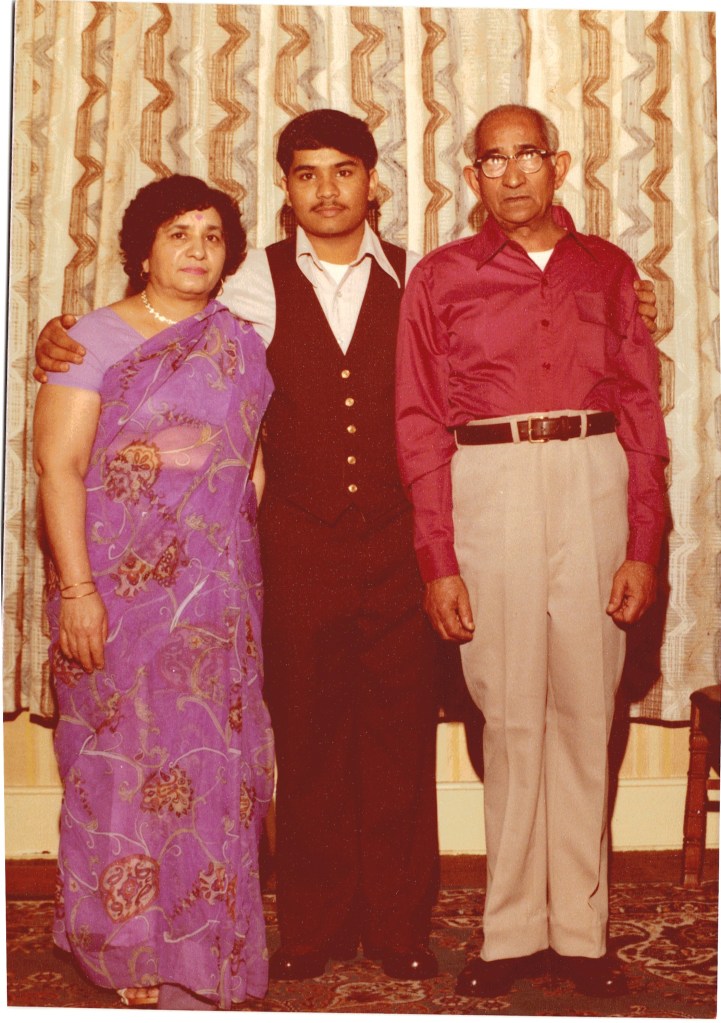

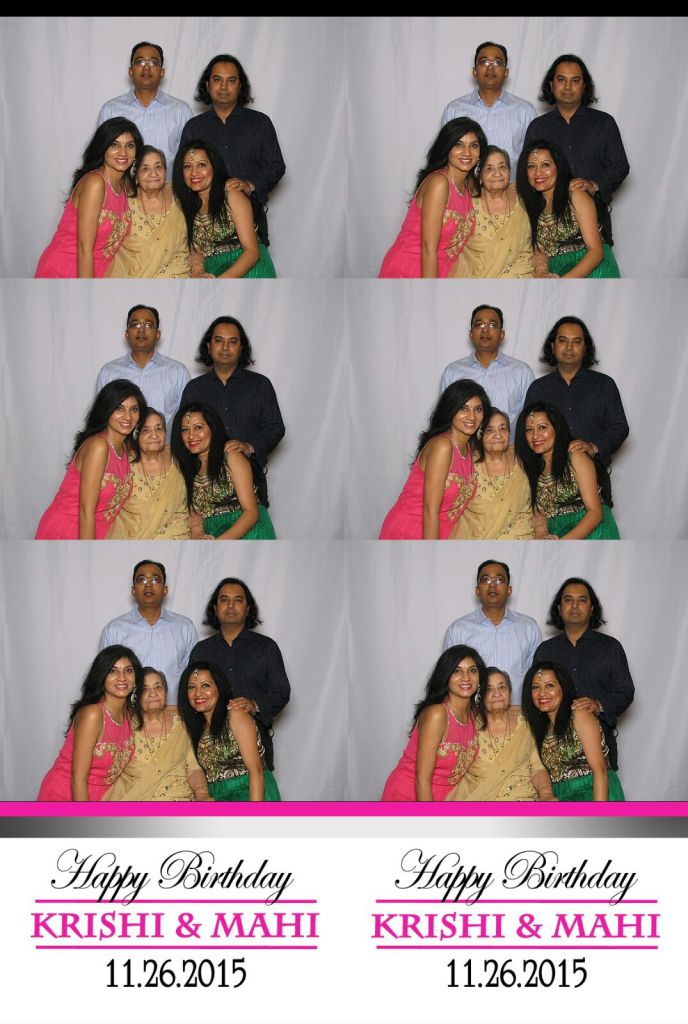

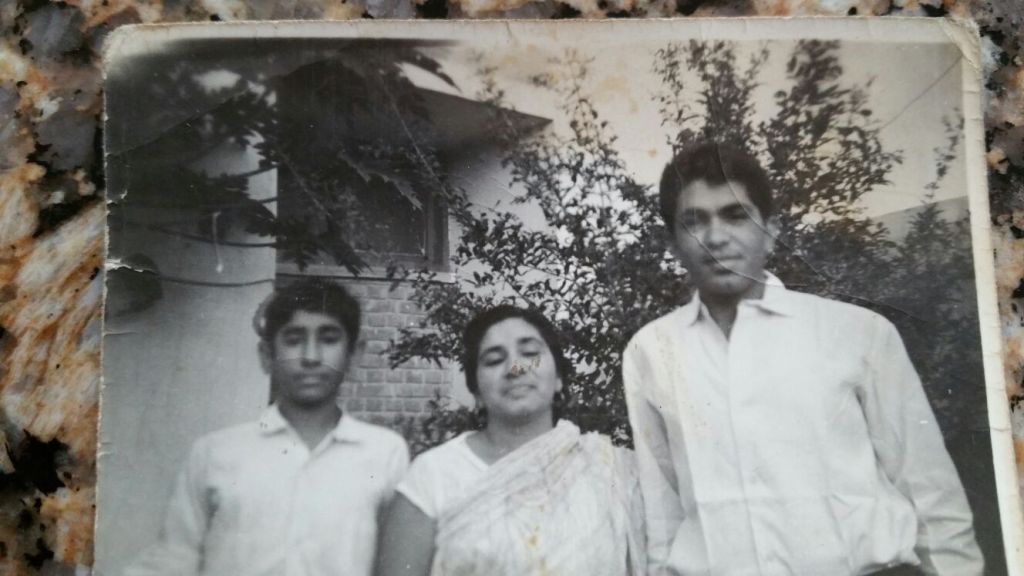

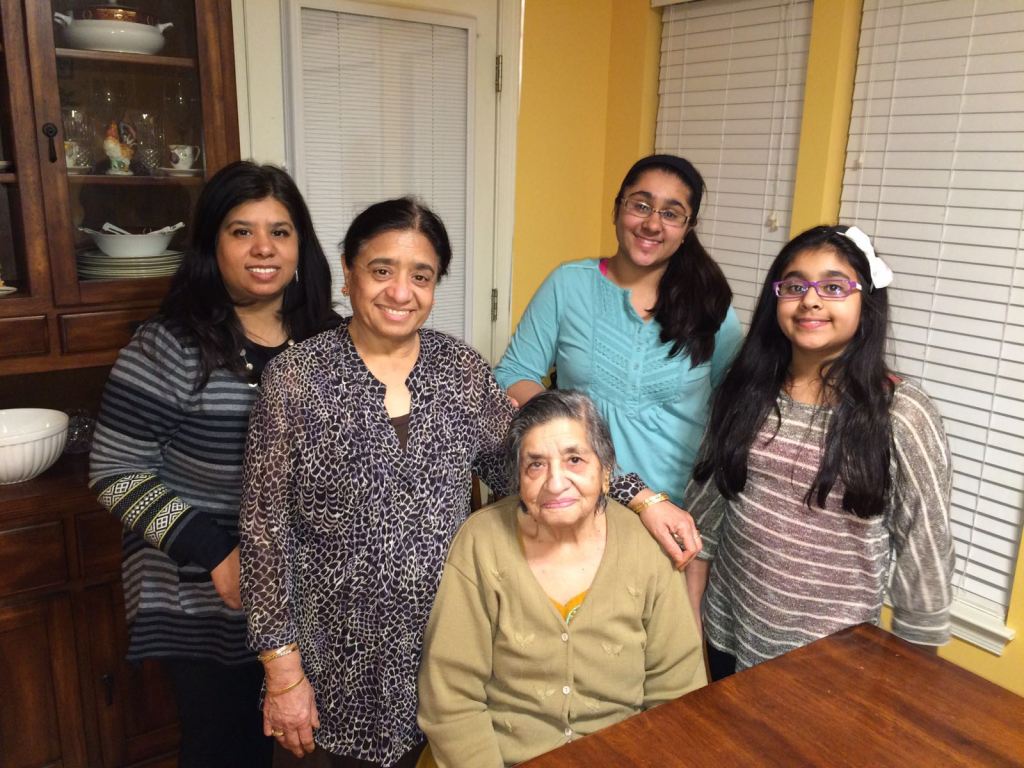

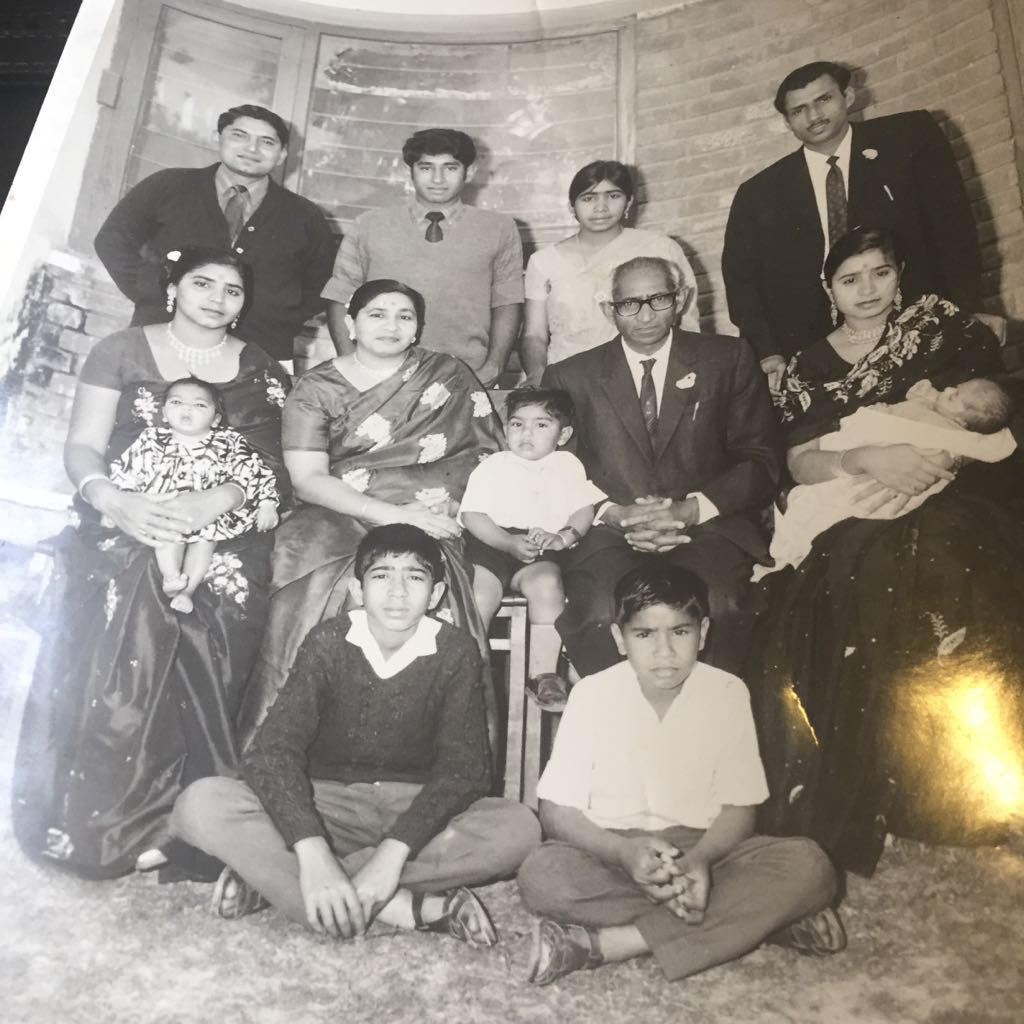

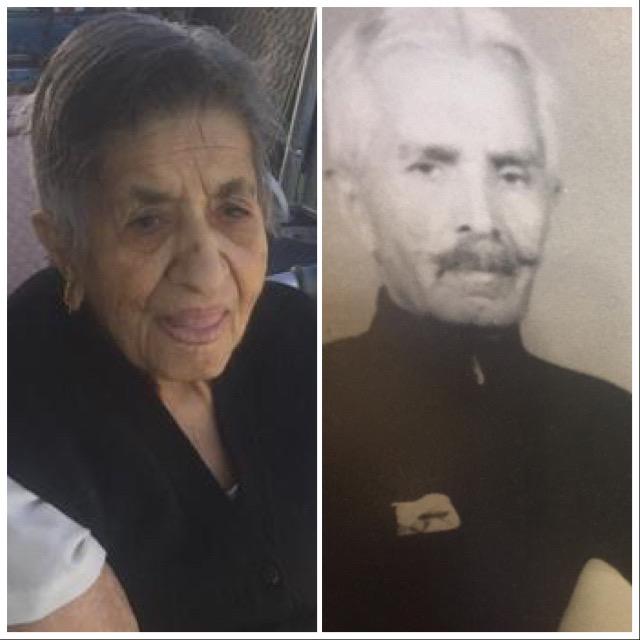

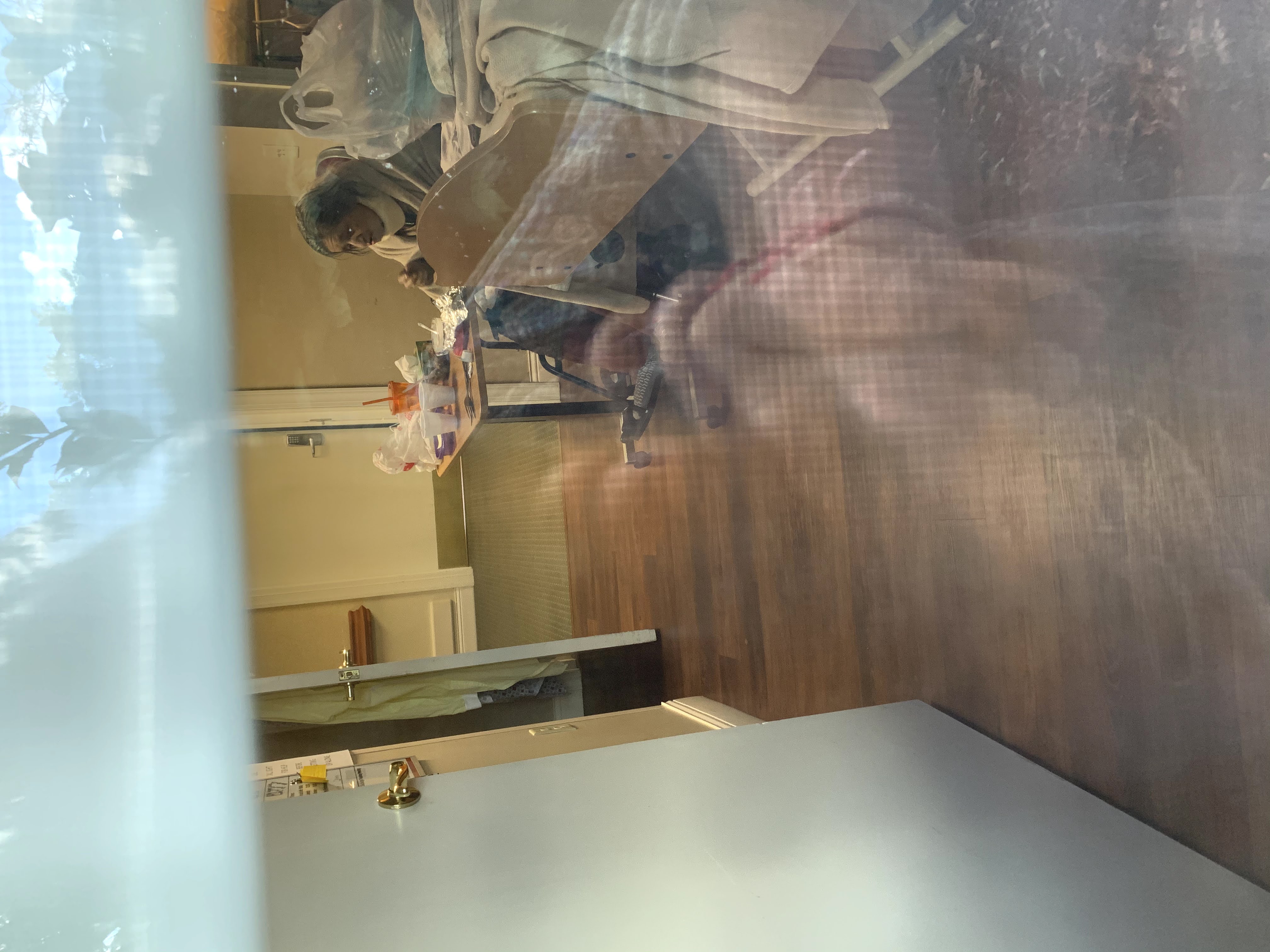

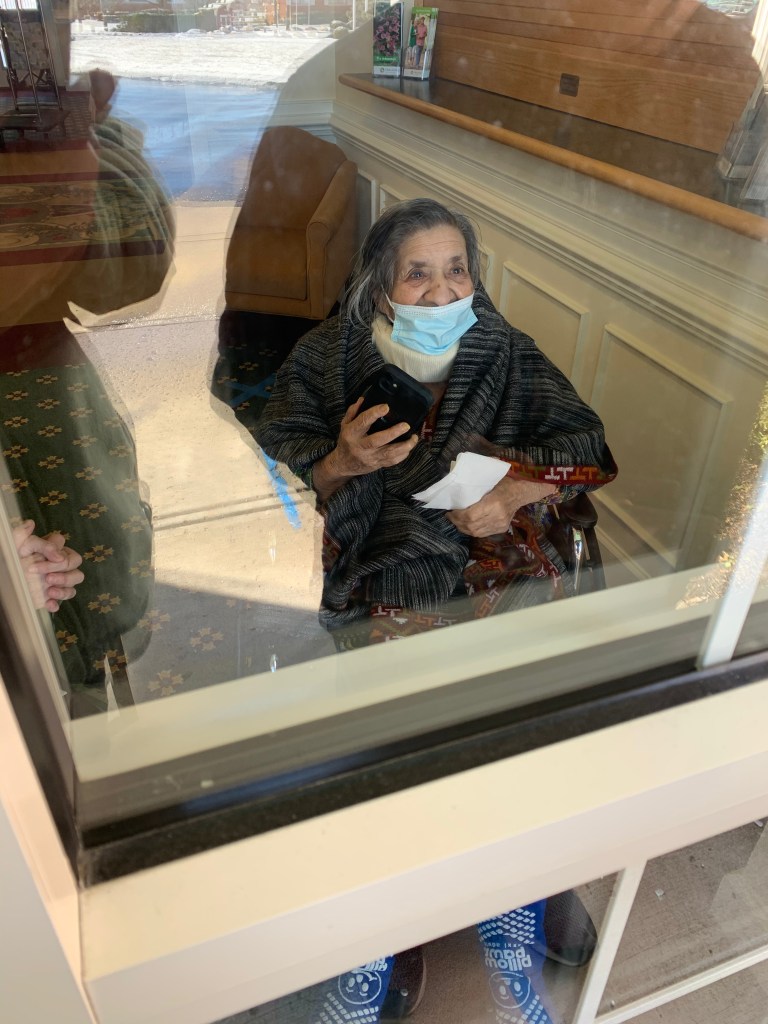

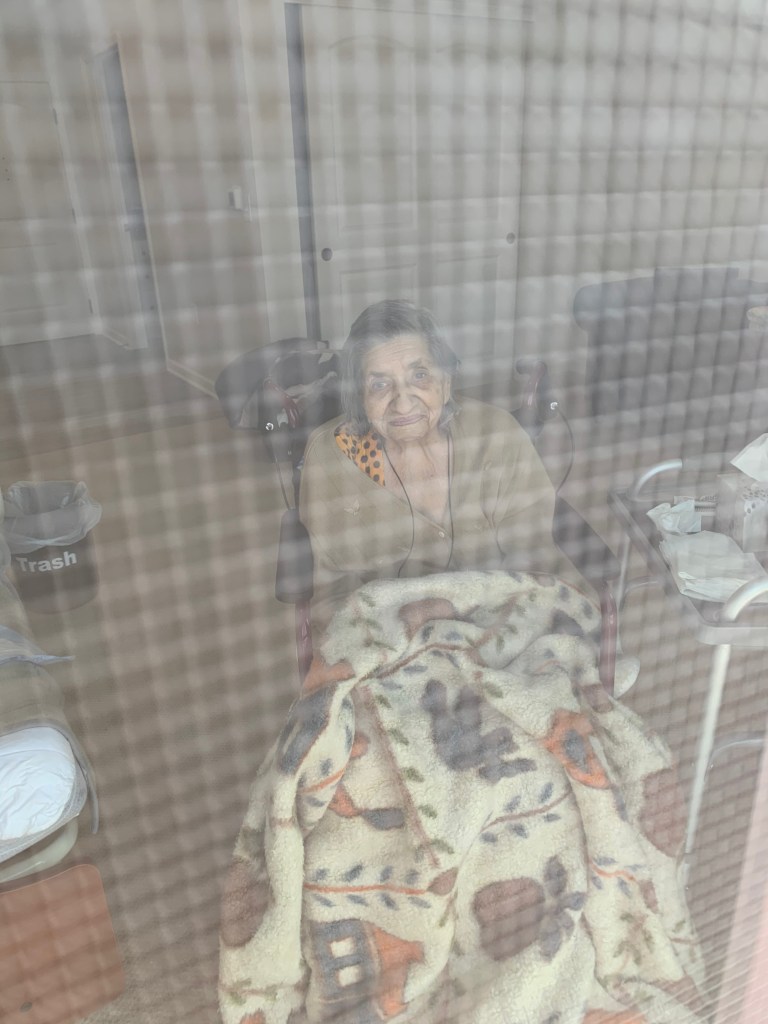

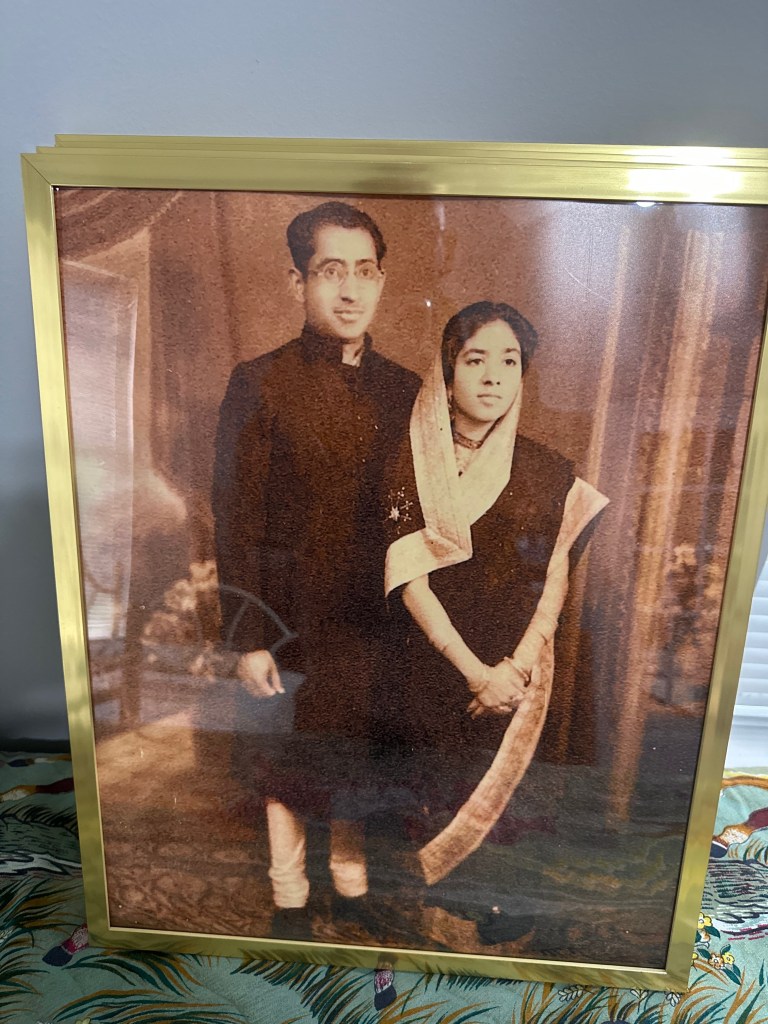

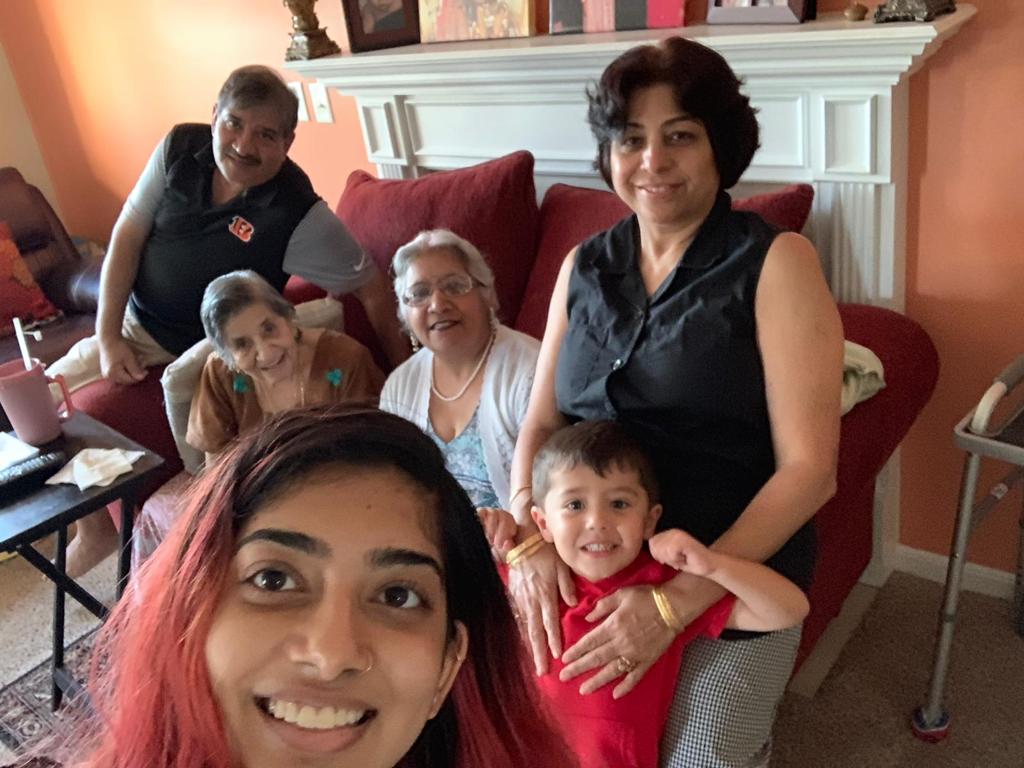

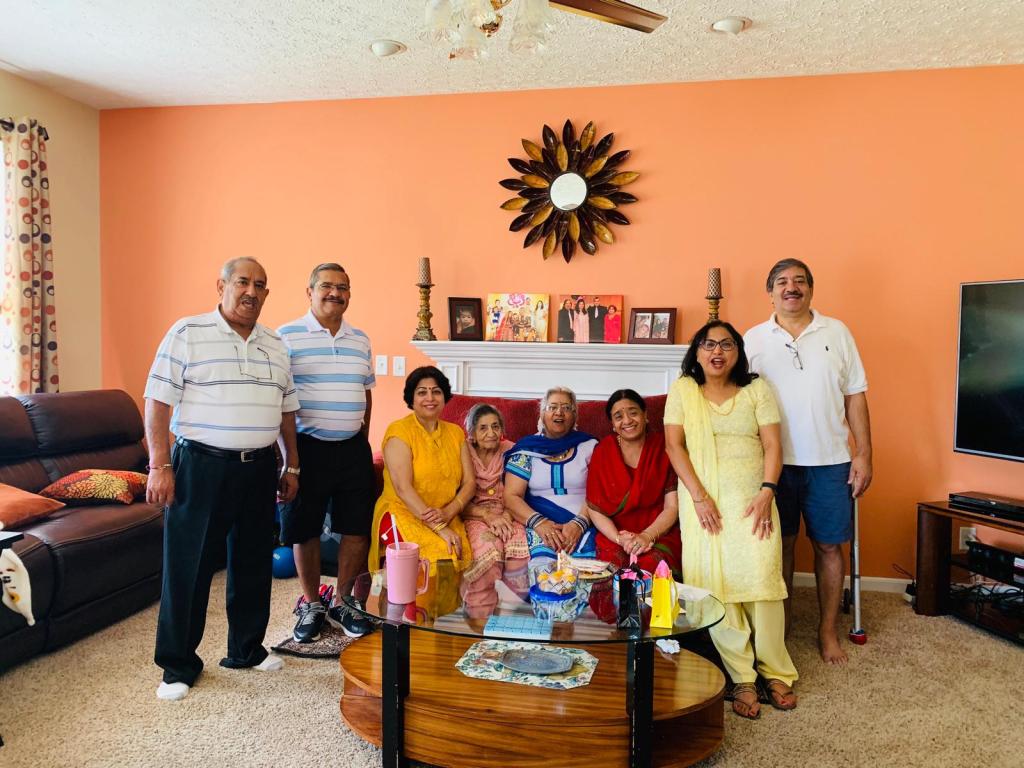

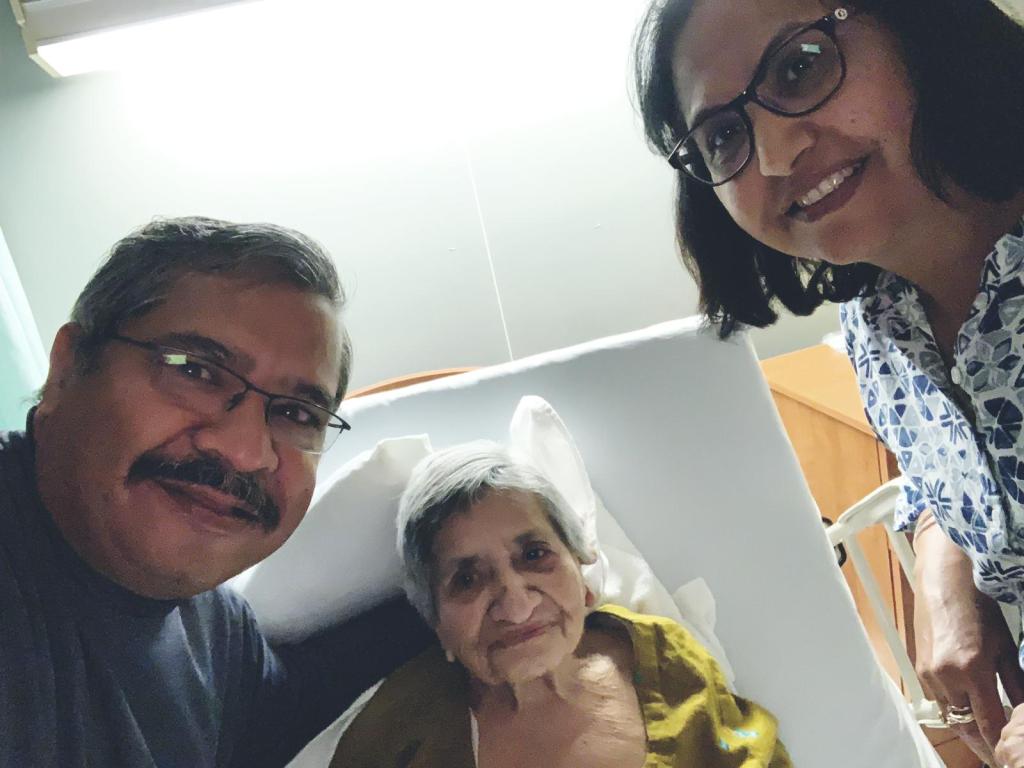

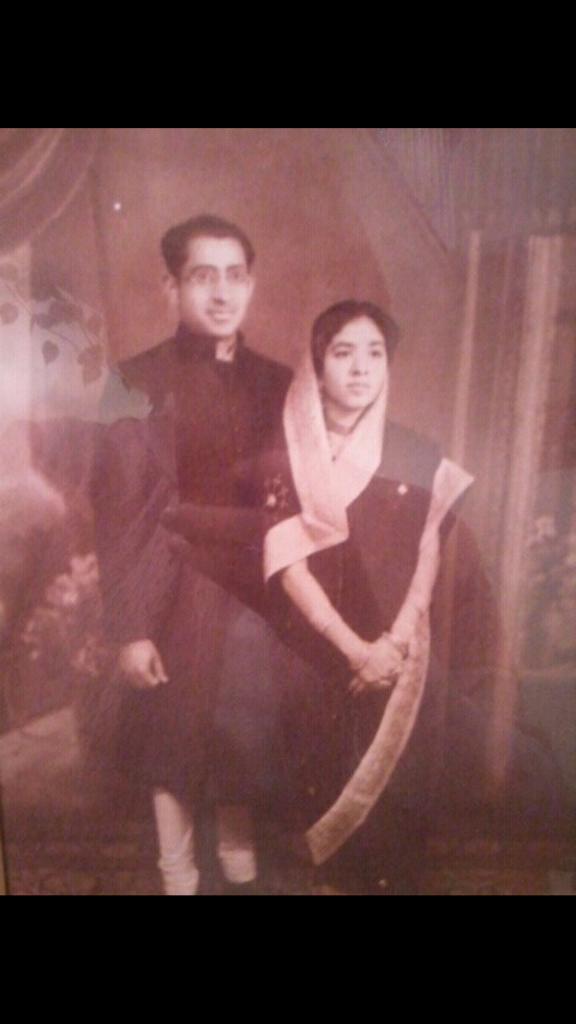

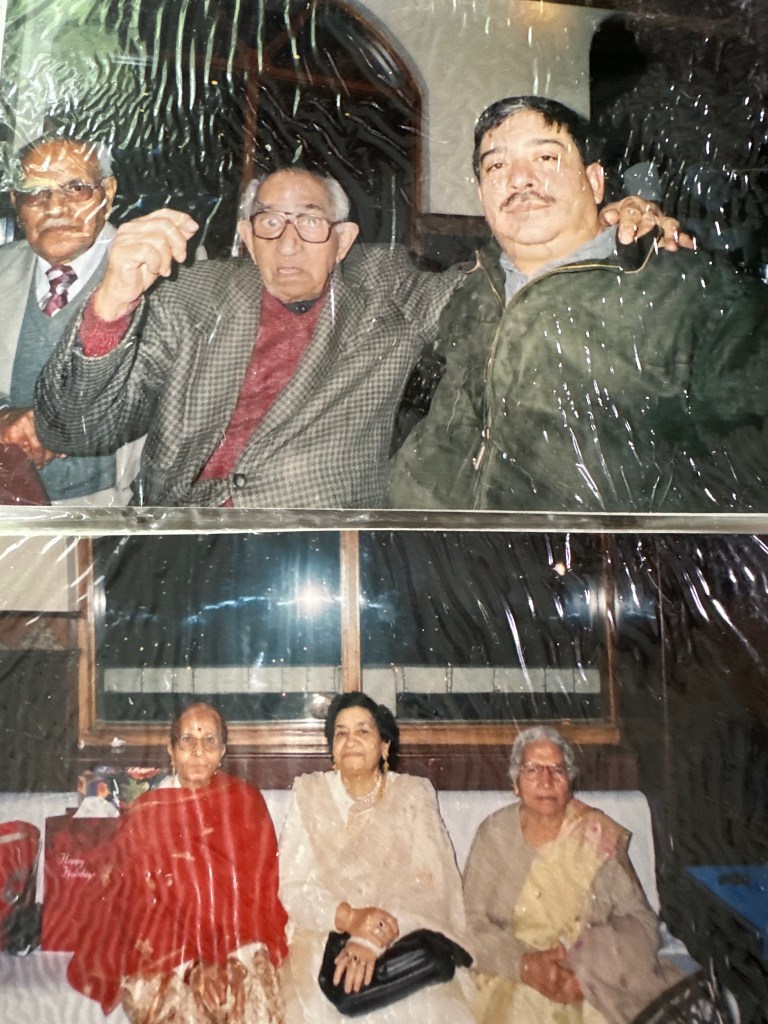

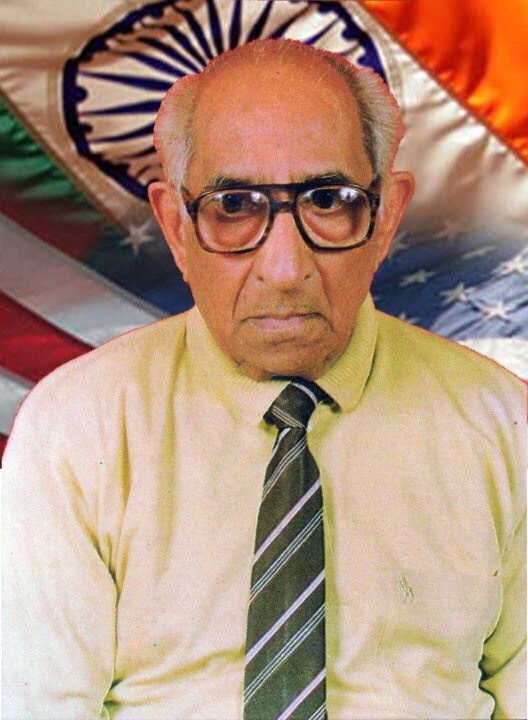

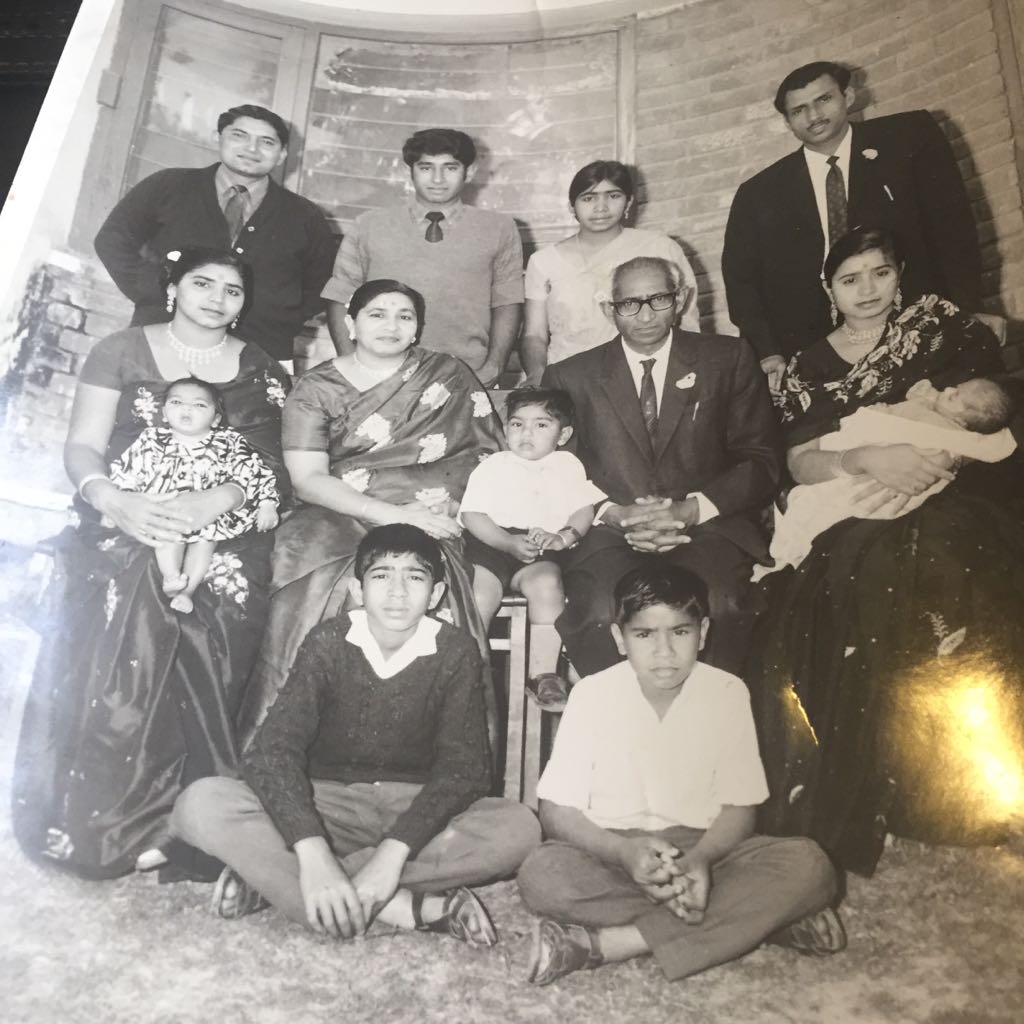

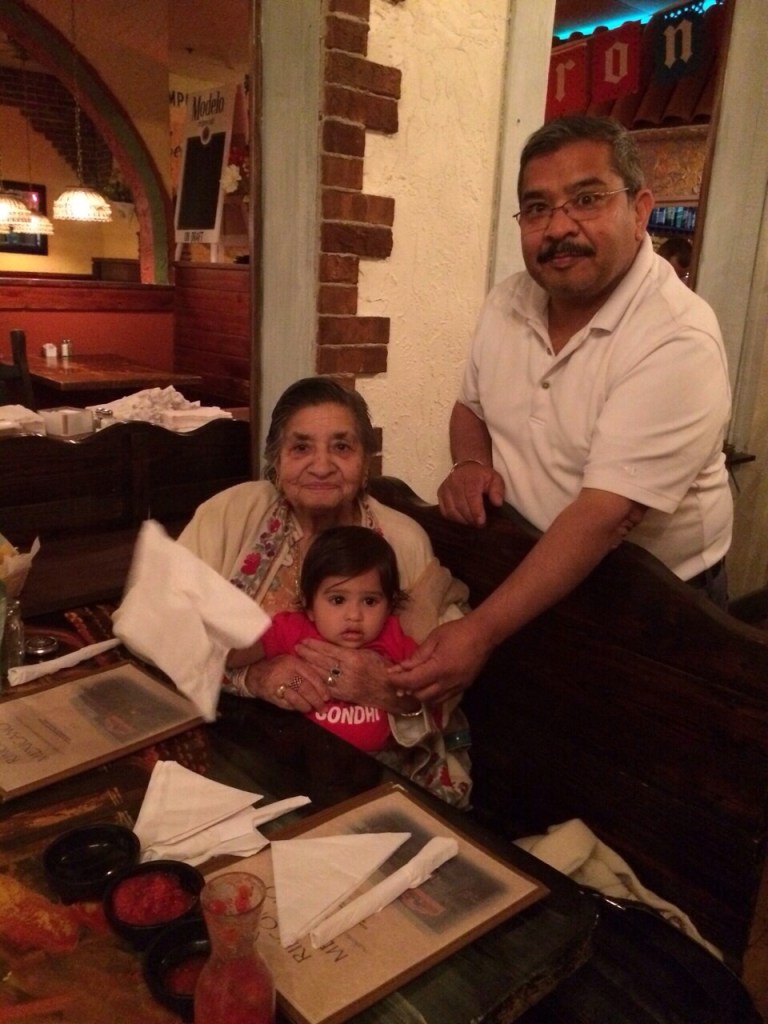

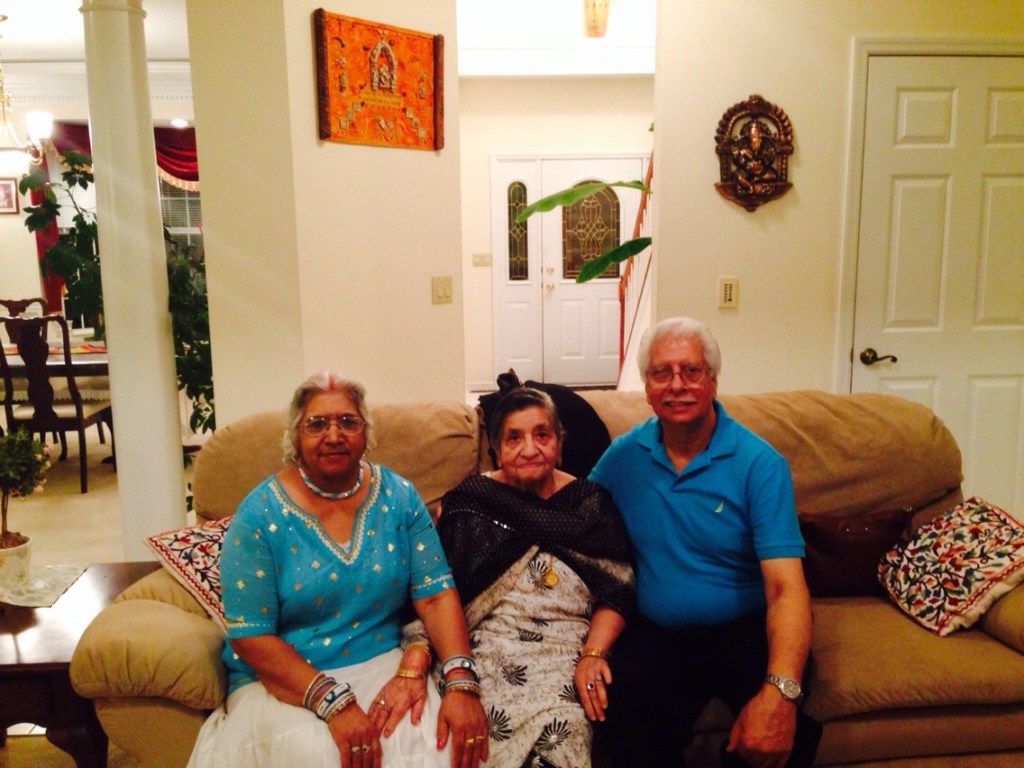

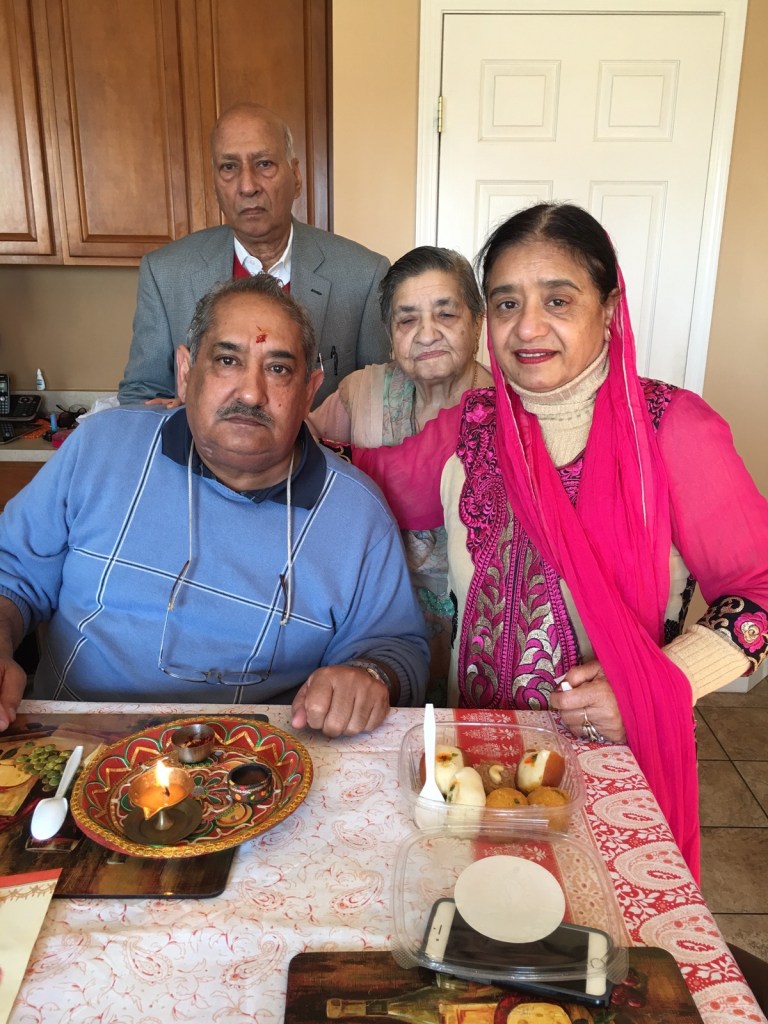

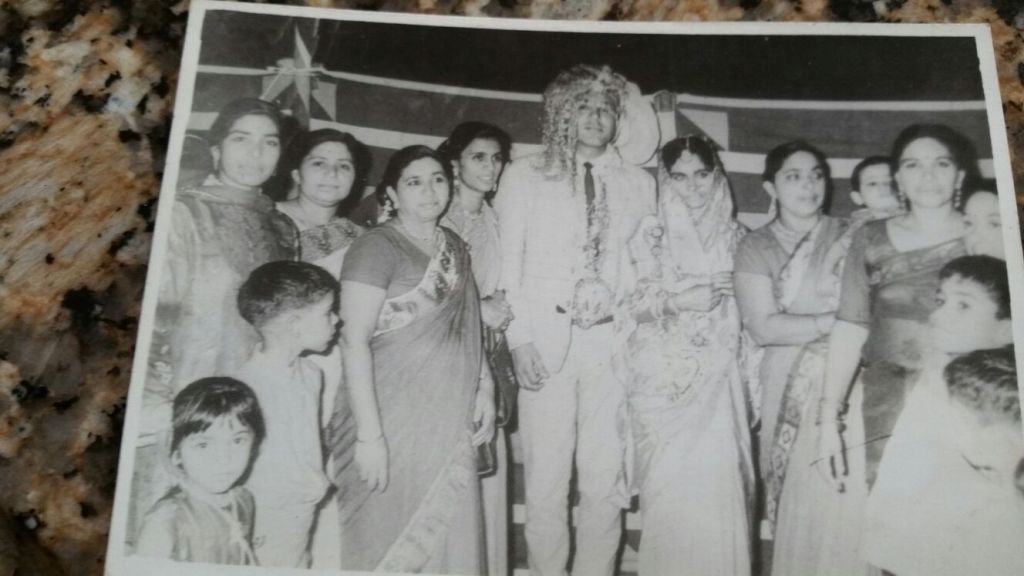

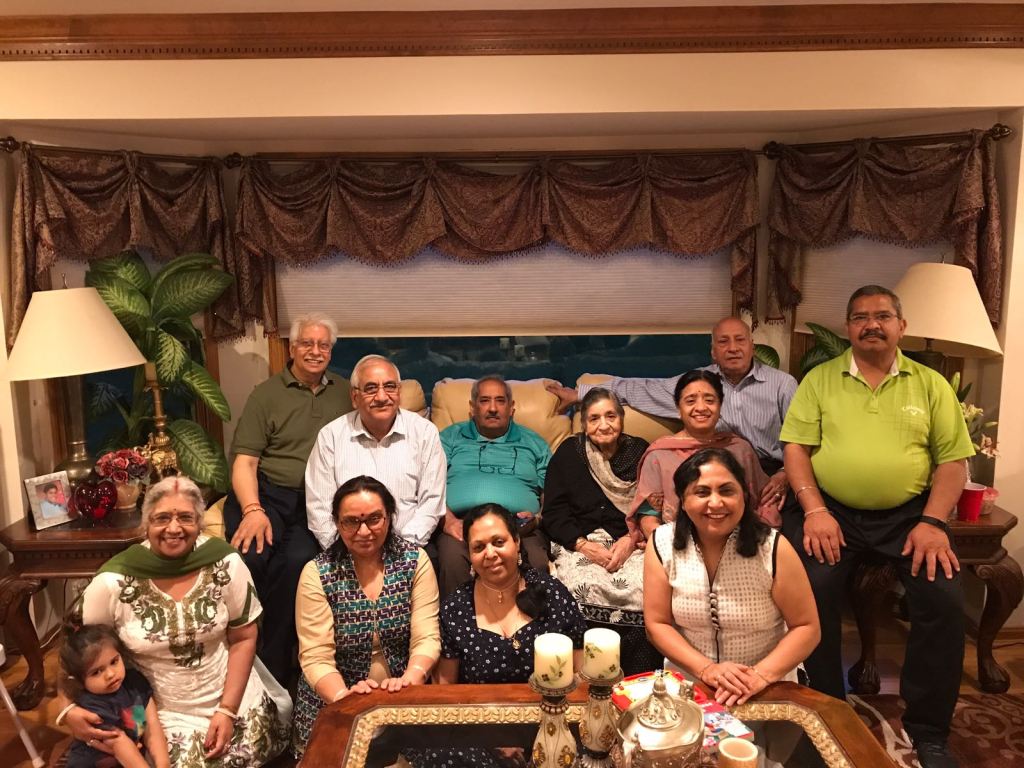

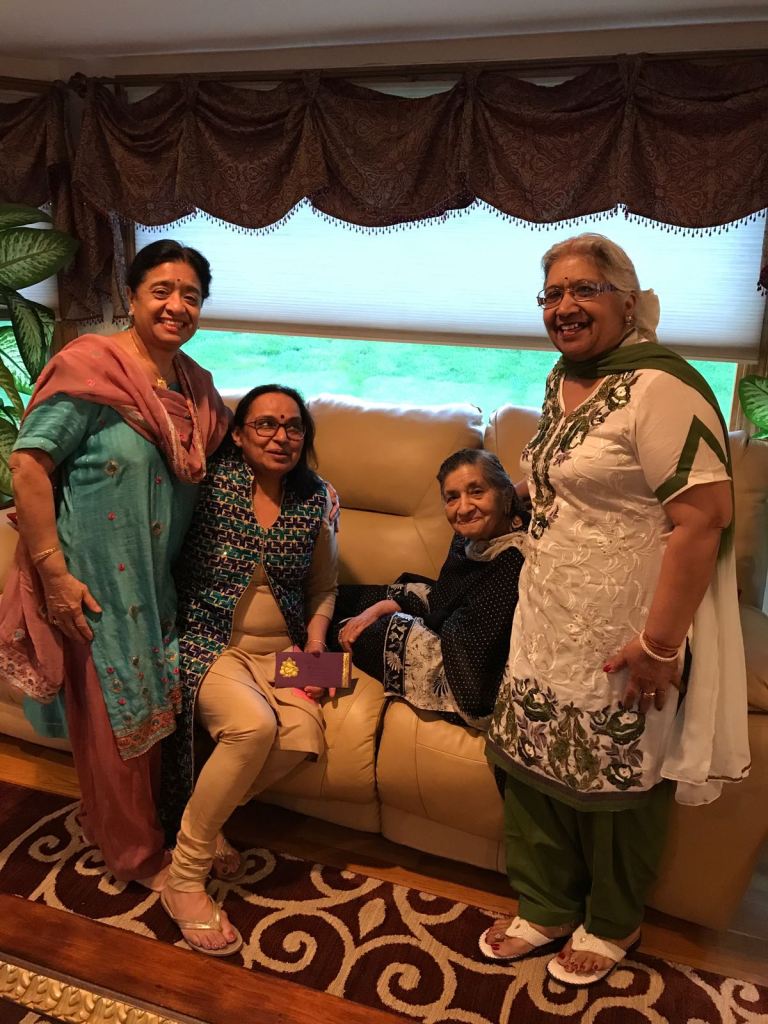

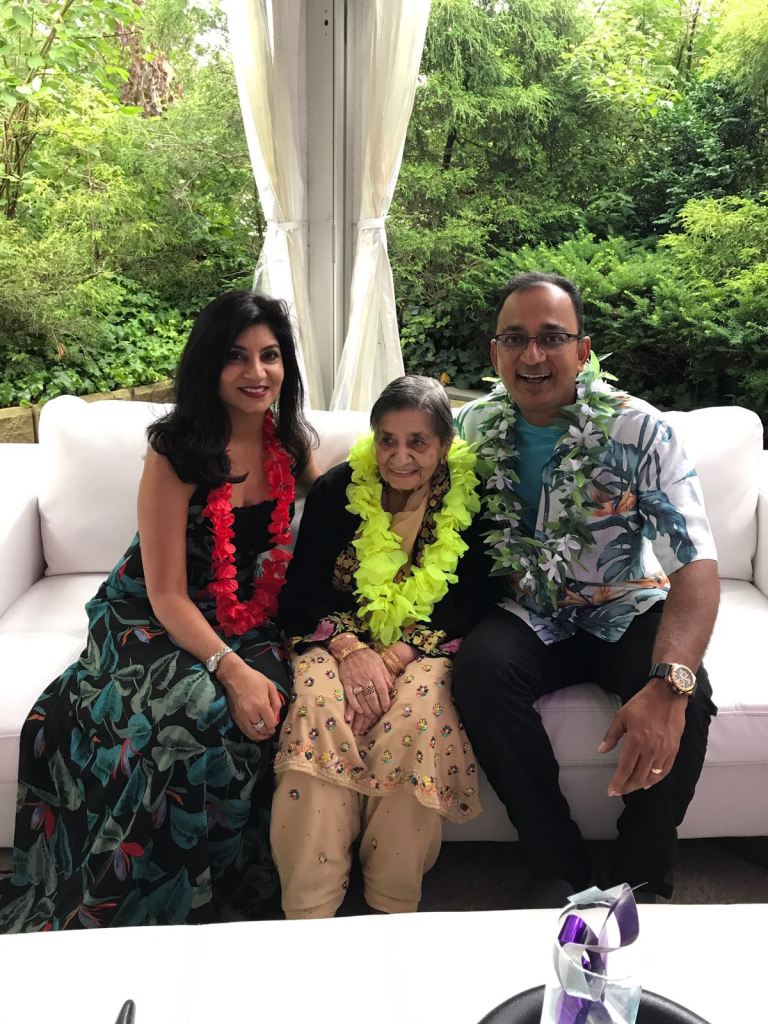

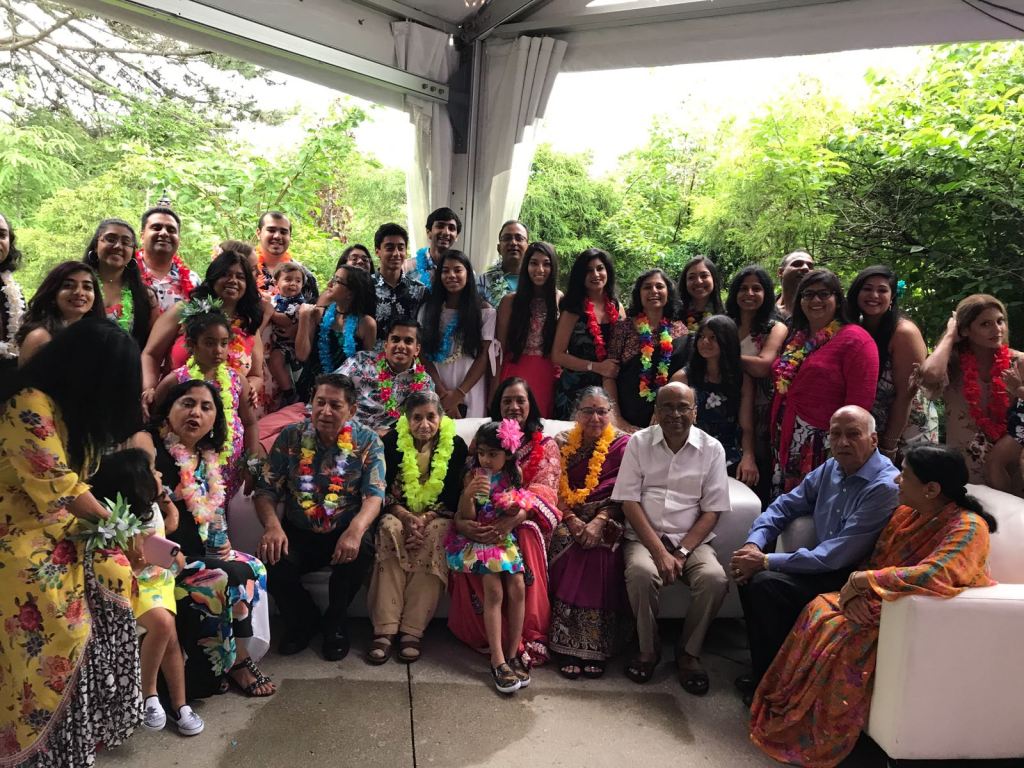

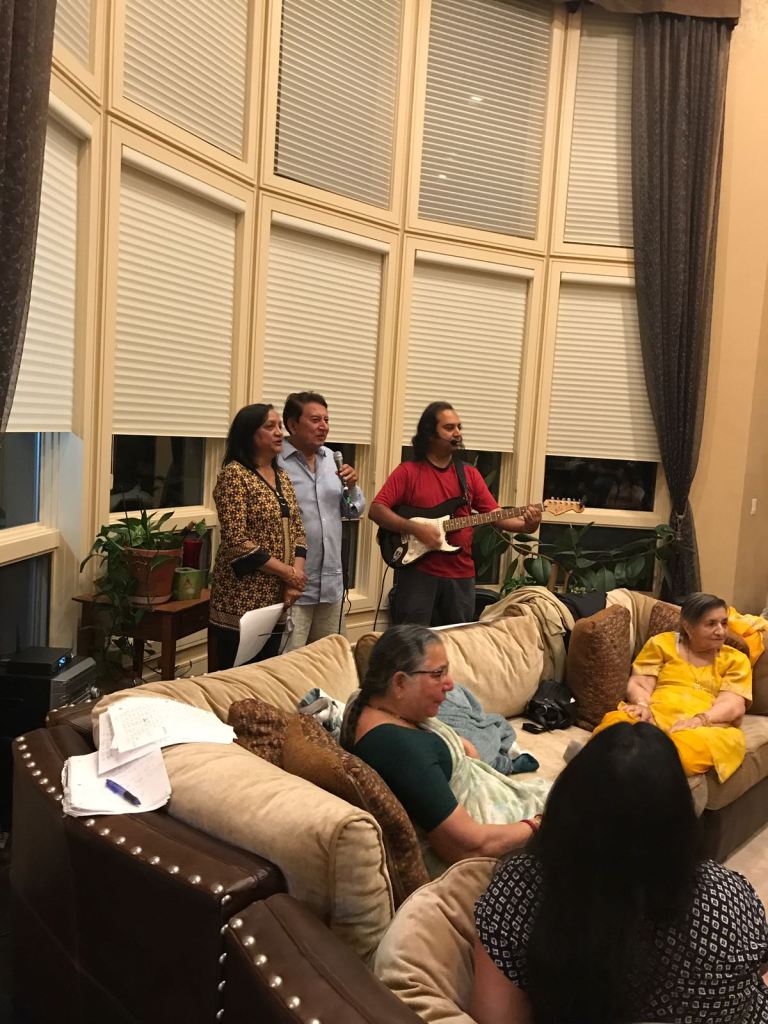

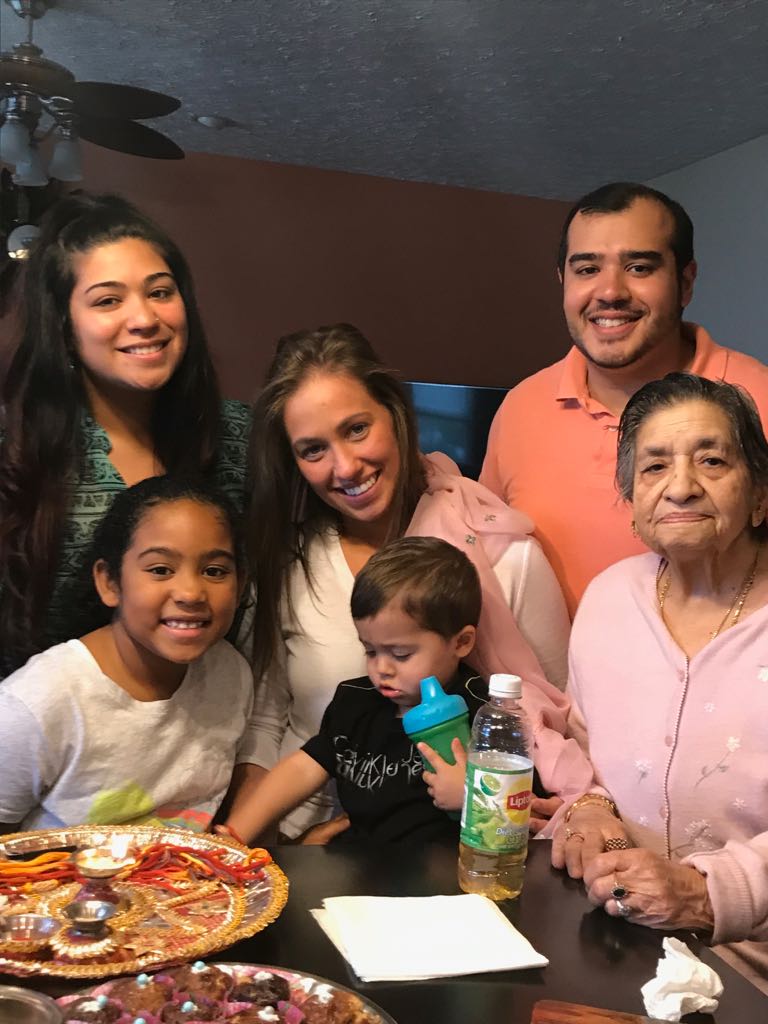

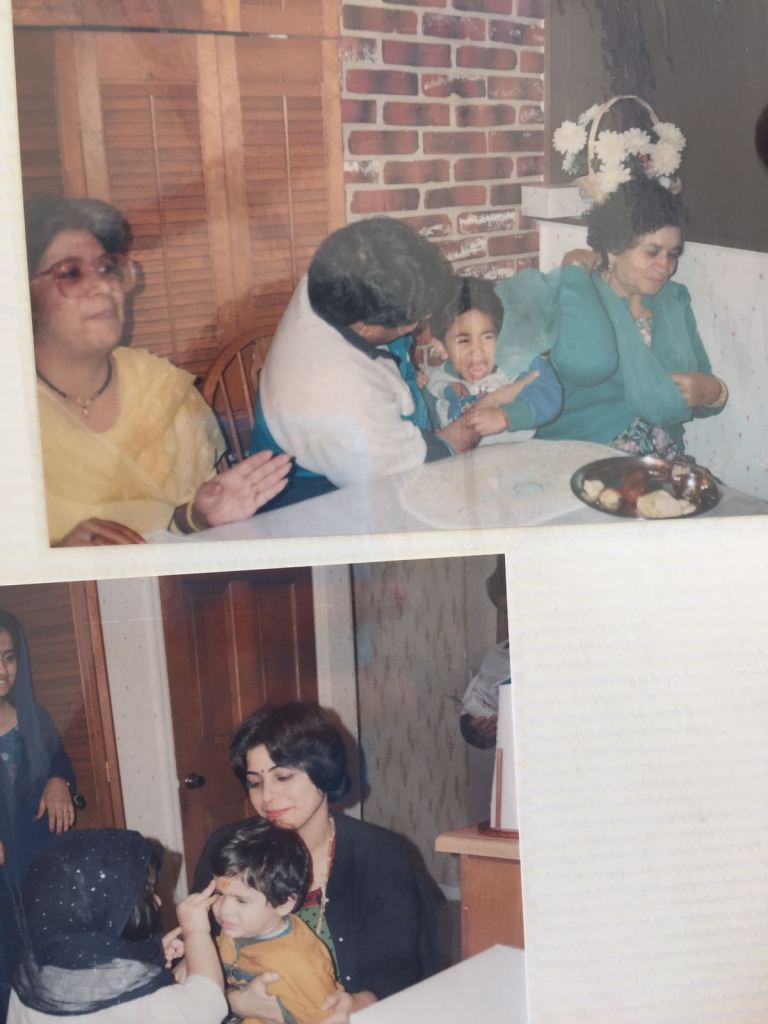

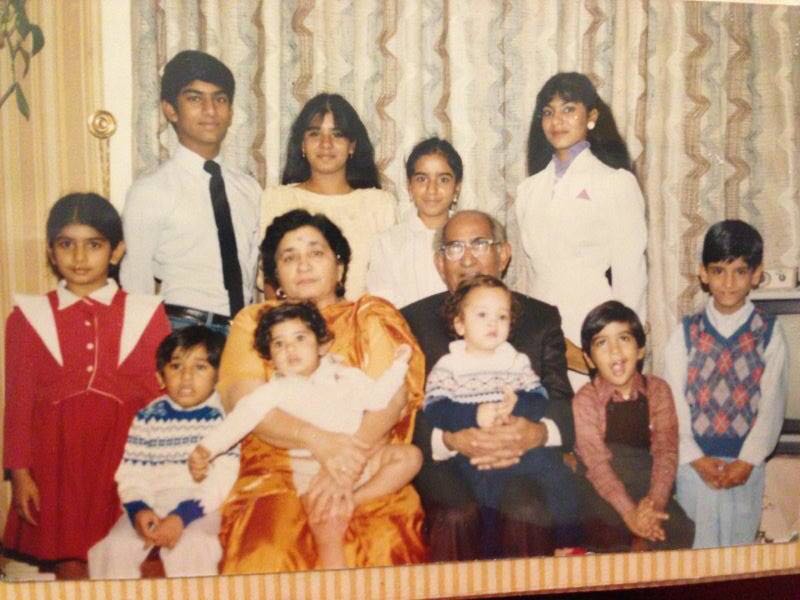

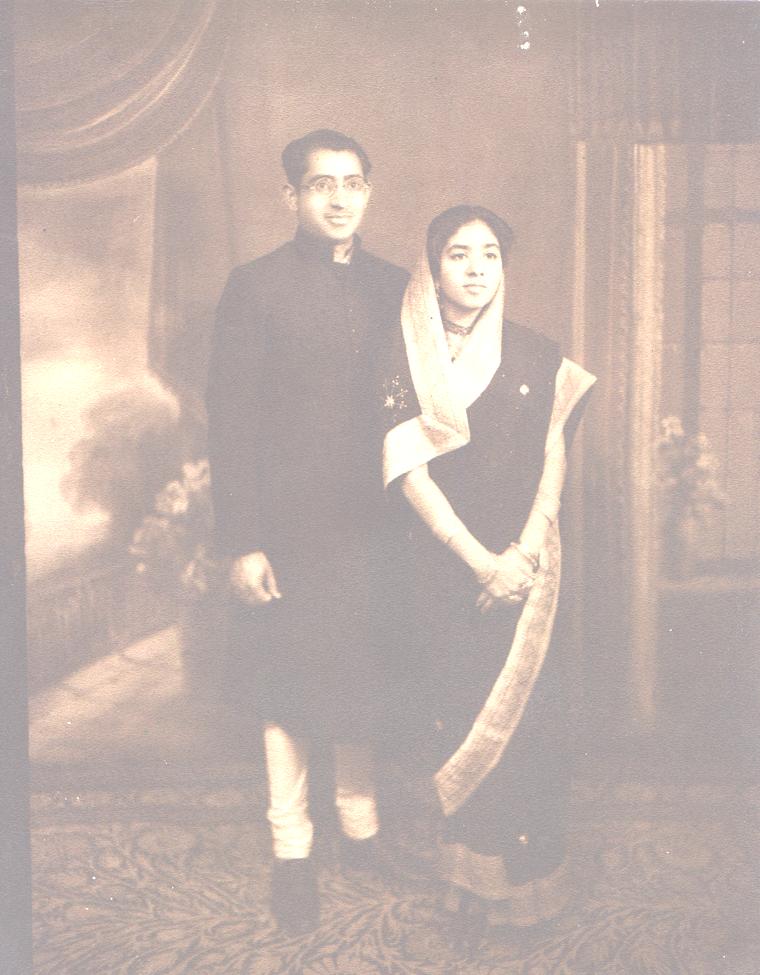

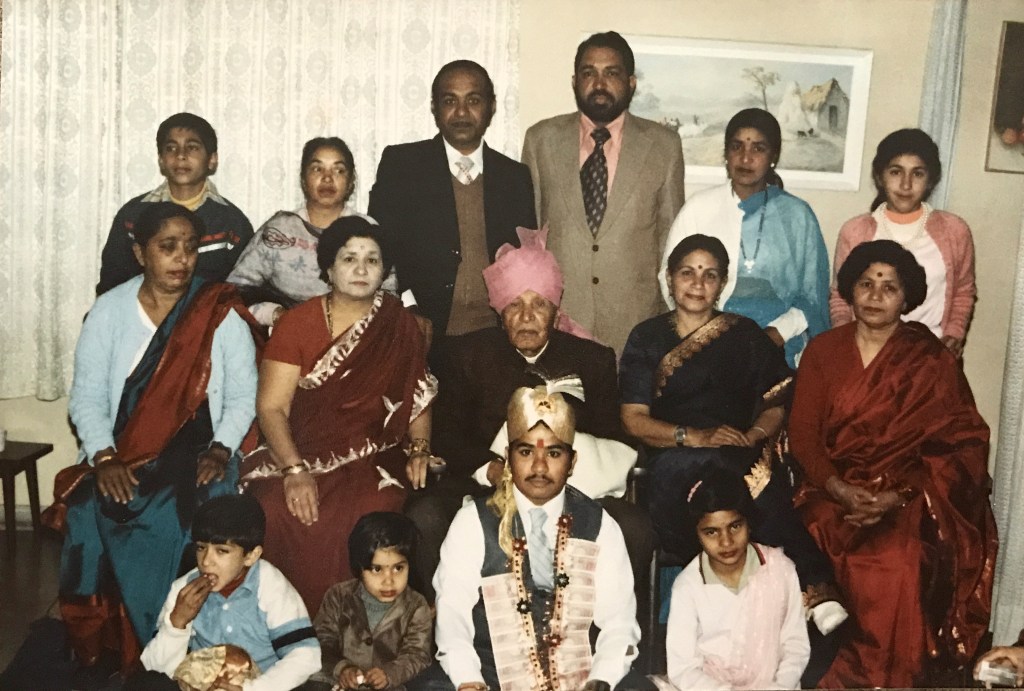

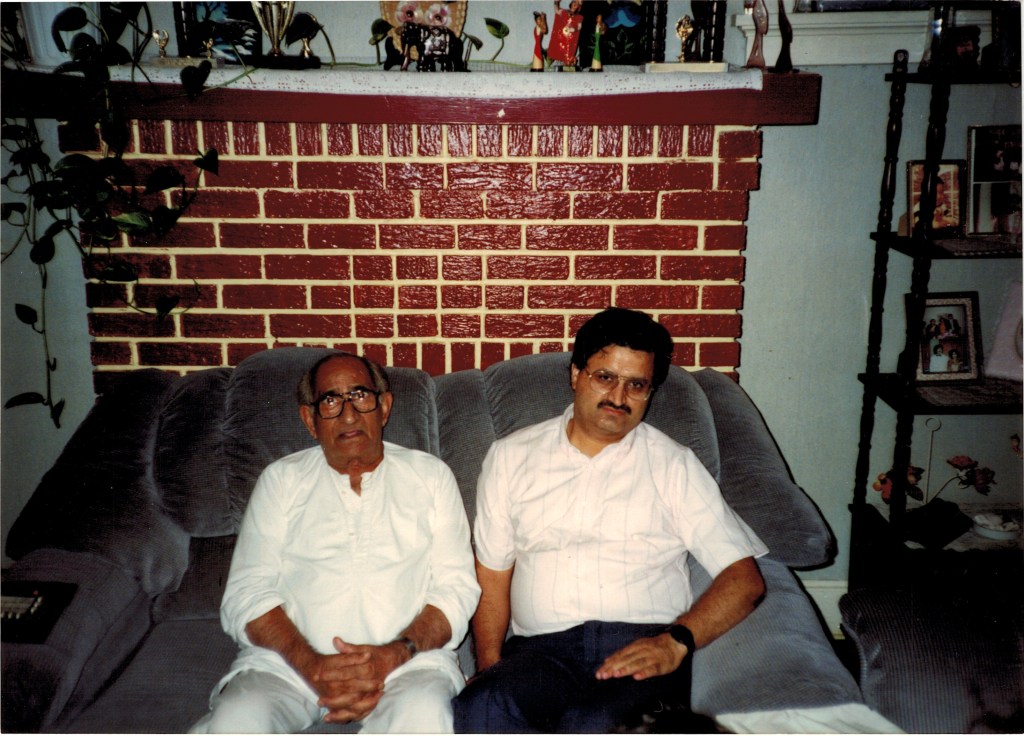

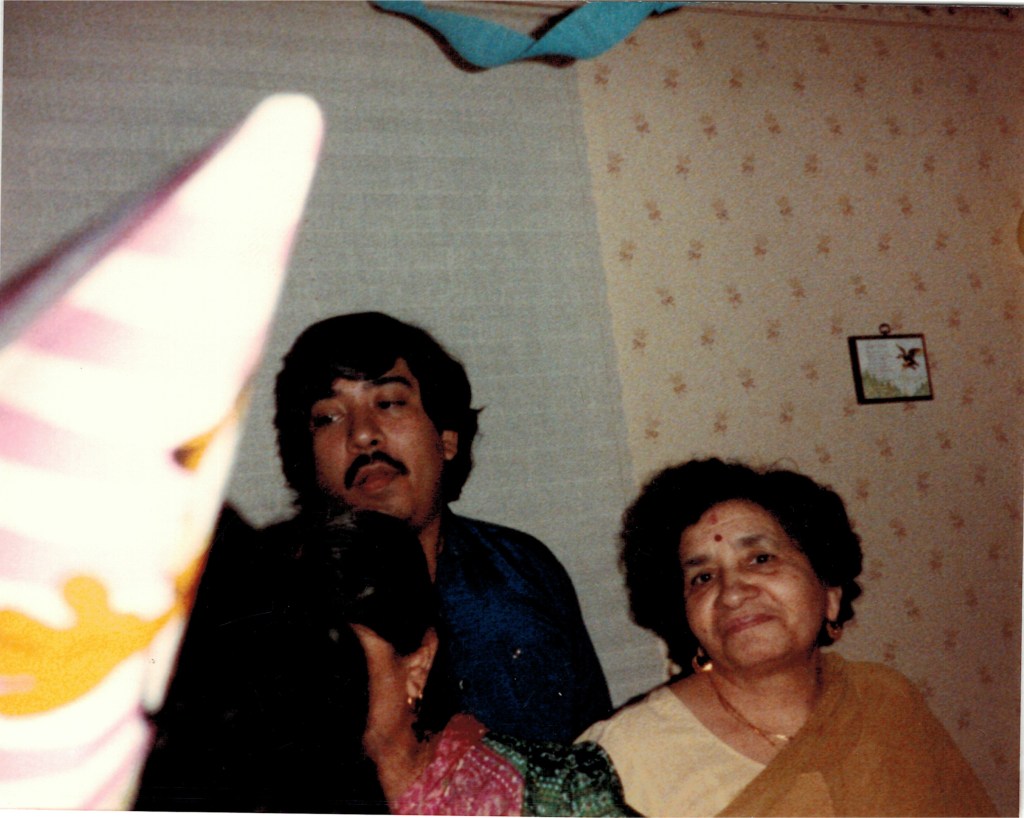

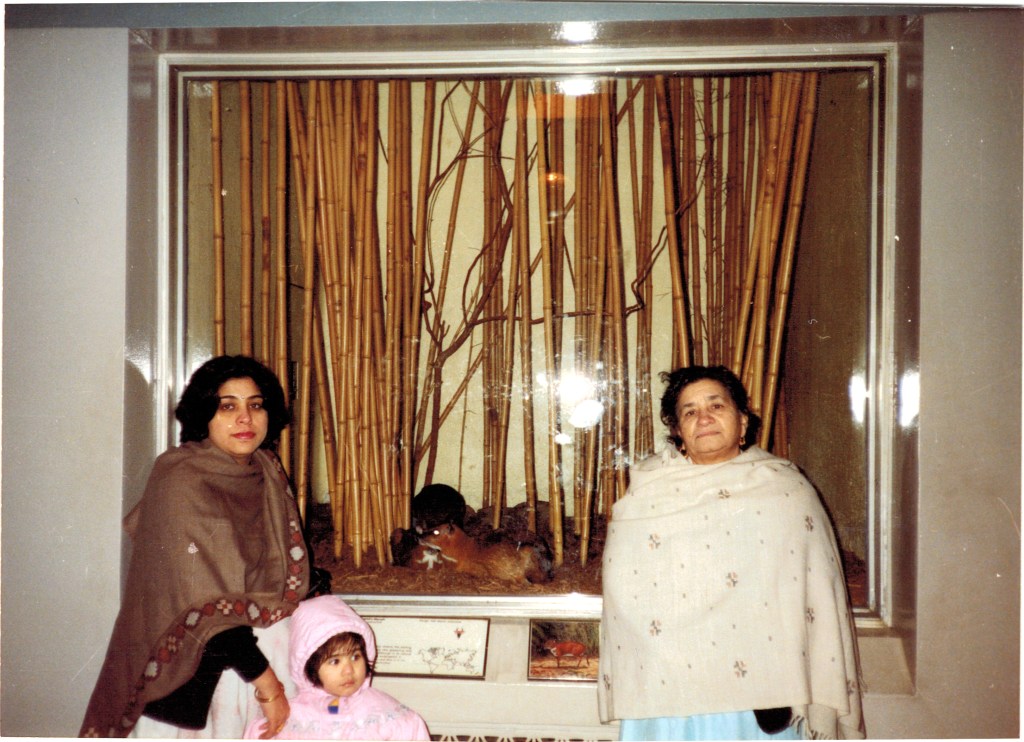

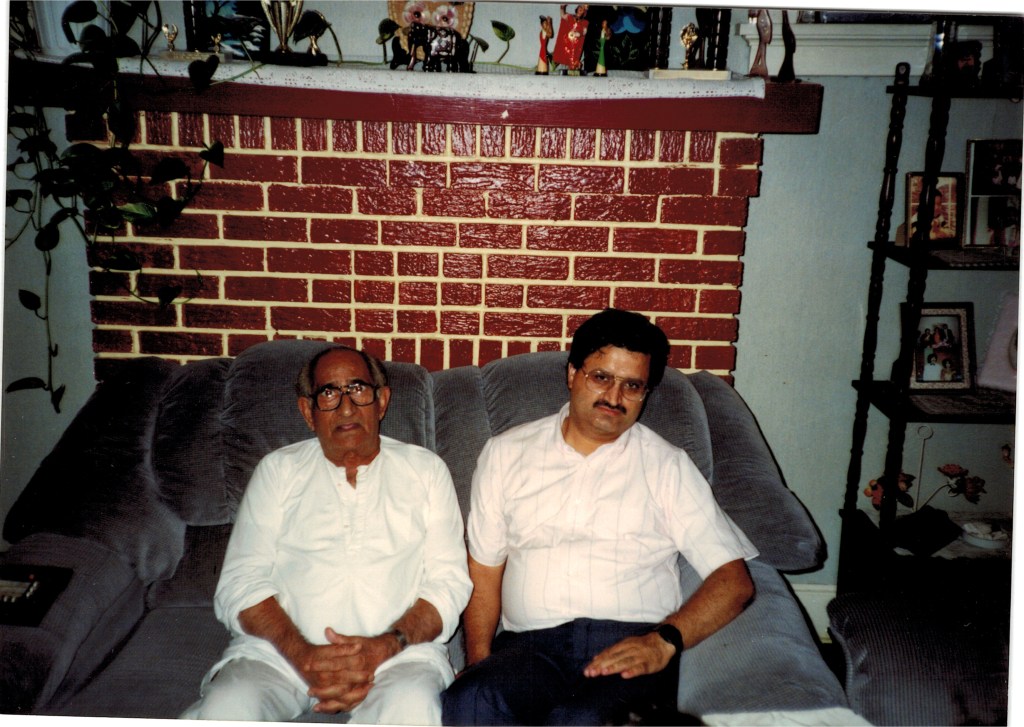

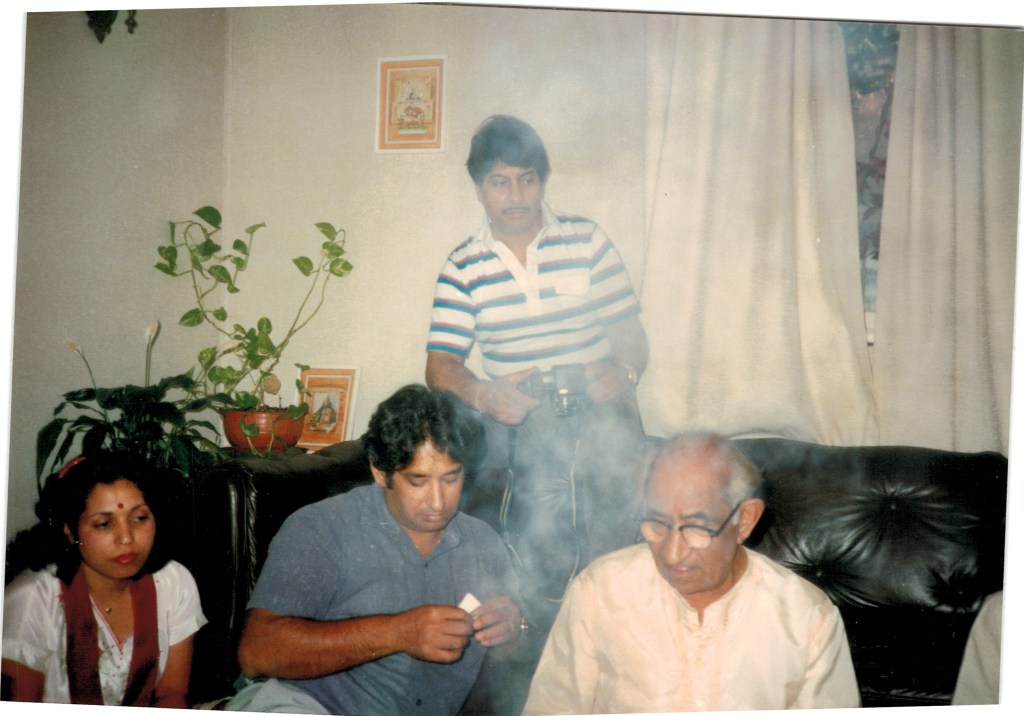

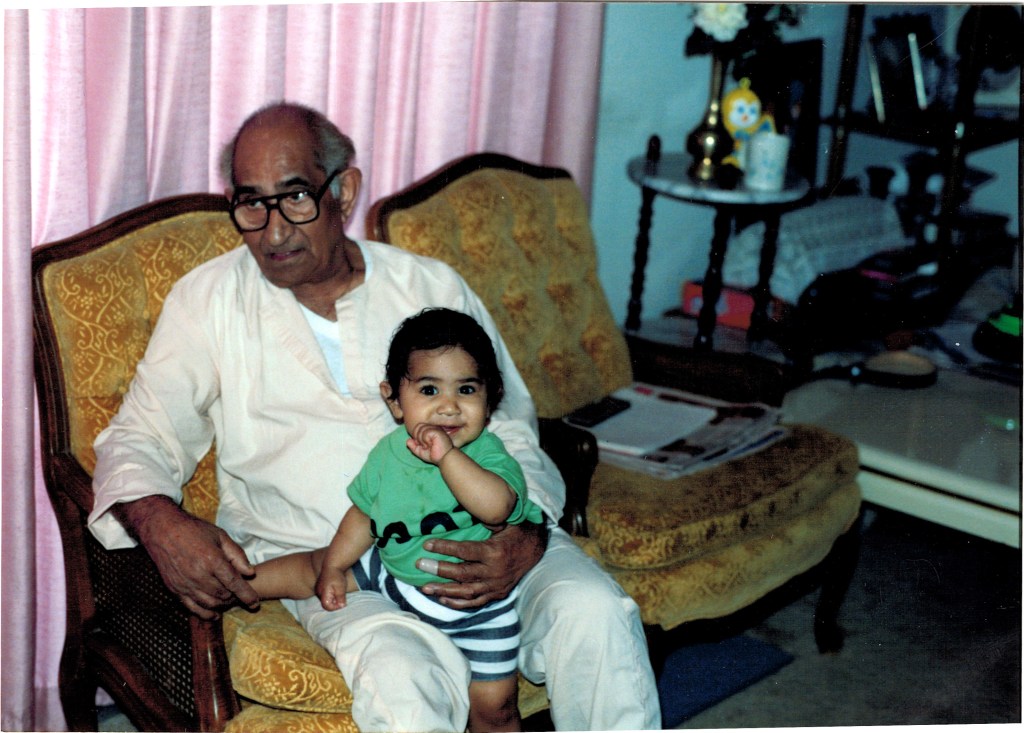

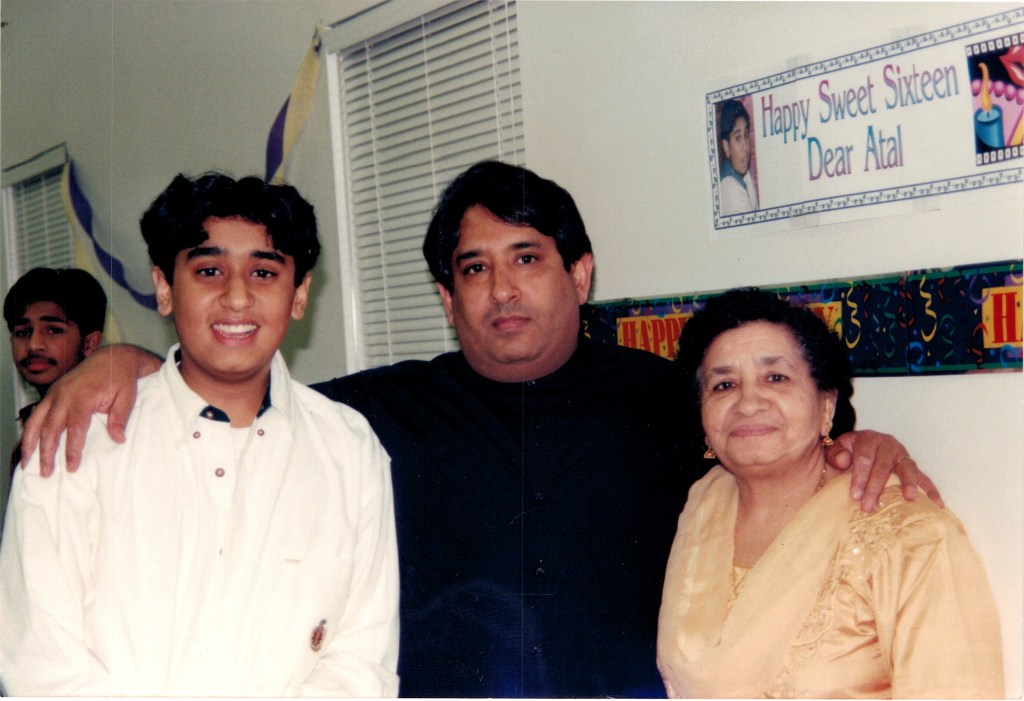

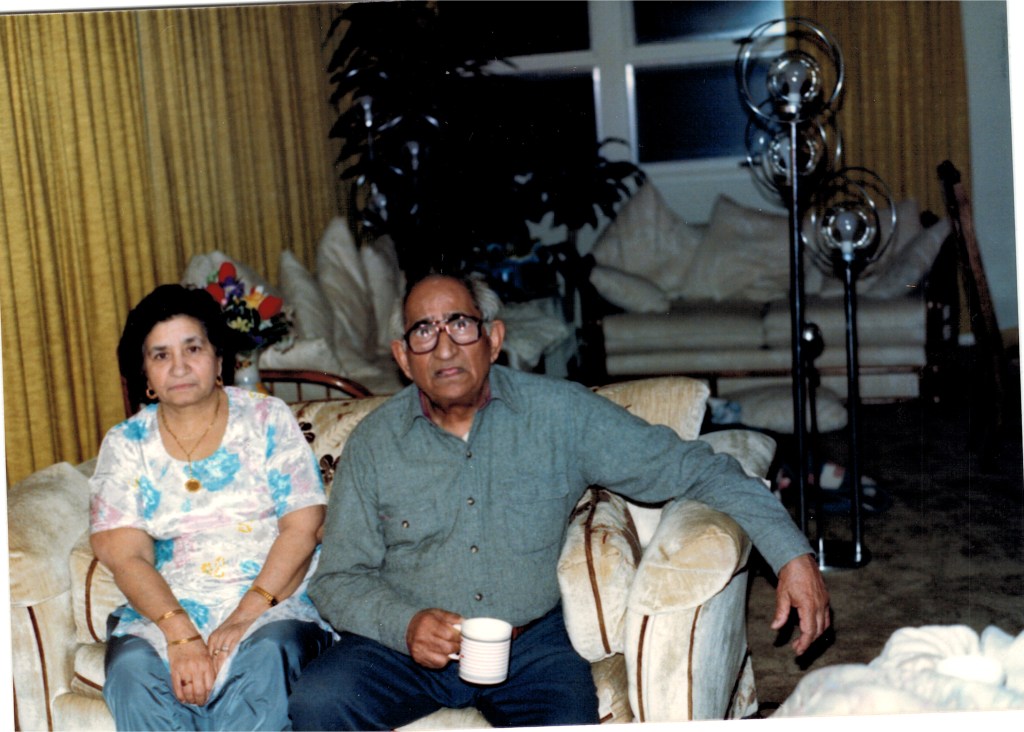

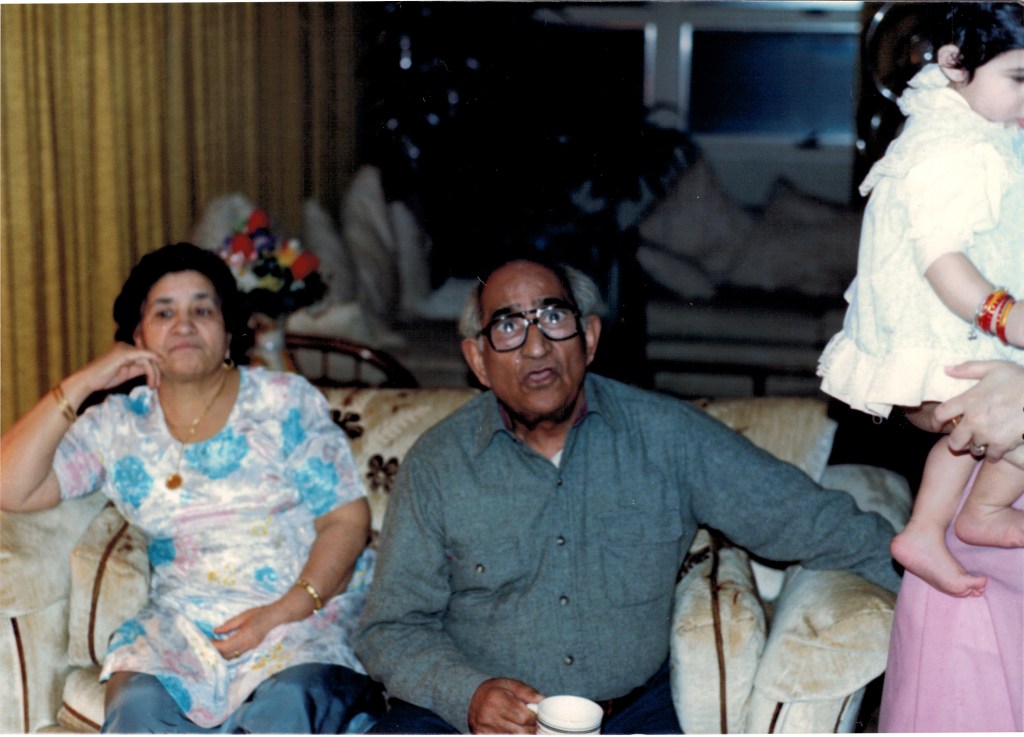

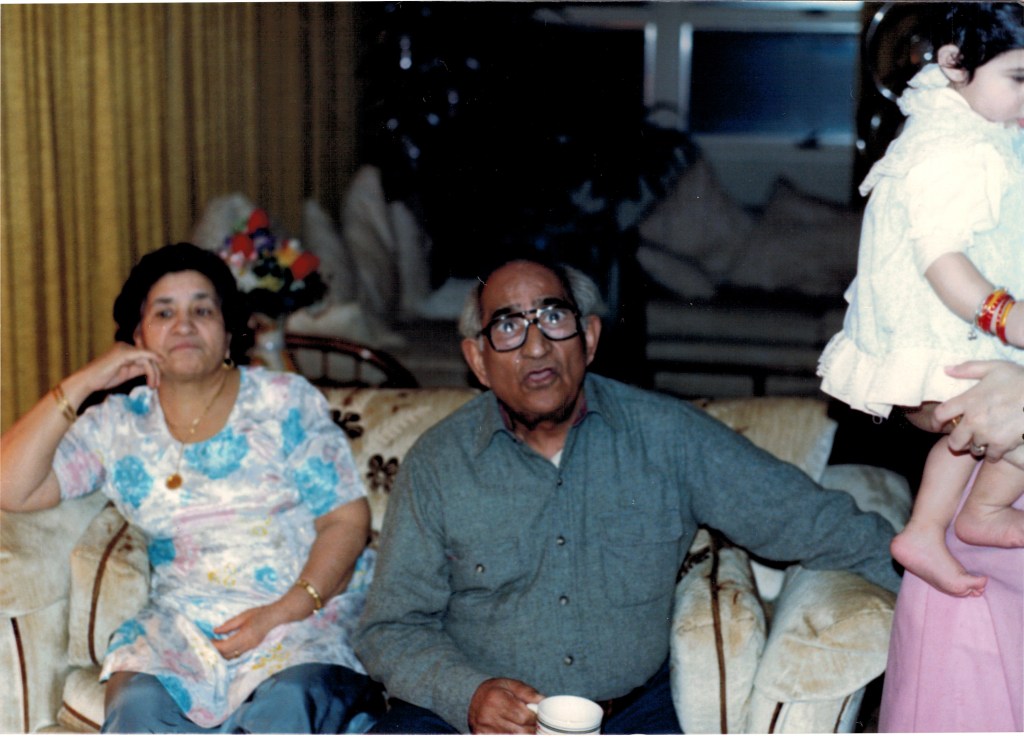

Nanaji & Papaji album

MNS G7 IN10 N1 O2.00 Y0.00 C0.00 YT0 CT0 s0 sY0.00 S0 C0 FM4 FC000000000:zzzzzz0 c164 0278044079c3f65883c014c0 bac ee202 52 5c34426832c 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 032c315831514b153 0321315e31514b153 03123146313f4b1 b 0317311b311a4b1b1 031c3121311f4b153 03213130312e4b153 0326314731434b153 032b3158315c4b153 03303167317a4b153 03353176318c4b153 033a317f318a4b153 0335317c31864b153 0 8 b 6 8 e14 5 8 3 5 6 8 7 4 a c 6 8 3 4 7 8 2 4171c c132129141e 8 5 612141b f14 7 9 5 7 d11 f131d36171d181e131b1b2412191d261f2b c10 b f161e151d3141311931533094306230893081309930a2304d306b3049320e316a32983192309a30a6322031e330d93100319131a23422327131f731613164311232bd334330a53096315a318530df311131633096307a308a30b630c630a13052306a304d323e3175328e3183309530ab321b31e930ef30f9319e31ad347e329f321a3159316631193298332930a7309b315a317a30c7310731603091306e308930d330c7309e304f306b304b322f316532573166309130ae31f031cf30ea30ea318e31853461327031f13142312c30ef323232ab3098308b312a315d30a930ea3159308430643082306e30b43095304d3069304831f6314131ff313a308230a731a6319730d630cd315b31483424321c31bc311d30e930c631b132053084308130fd312f30ad30ed317f308830603084306030a23099304e3067304a31fb31523210313b308130aa31b3319d30d230cc316131523453321d31c2312830ef30c931b43214308730843100313630bc30f931a630933064308d3055309d30a23051306d304b32153161322f314d307330c631ce31b230d030d7316f315a348f324031d8313d30fd30d131dc3244308930893111314530cb310131c9309c30703097305330ad309e3057306b30503227317232613162306430e931f331cd30c730e03184317834da326231f7315d312030ec321f329a309830903128315e30d7310731d6309d3074309f305230be309c30573069304e322a31803299317030603128320d31dd30c130ed3195318b35093284320b3171313e30ff325532e030a330993143316930da310031cd309930753098304a30c03093304e305e30443230318532b5318c3058316e322e31f230be30ef319d319b3537329f321b3185316a311a329a334830a03093315e317630e930ff31cd309730833099304a30bb3093304f305e30453234319a32dd31b23058318b324a320430cf30f631a131a7354b32aa322f31923187313032cd338930af309a3173318d30f330f831c2309a30863096304c30ed30963051305e3045323c31aa331331da3059317c325331ff30d330fd31aa31b1355532ae32233186319c313632ee33b630b330a5317d319c30f830f631b6309e30953097305030ea309530563062304c322f31b2331731dd305d317e324331fb30d730fc31a531ab355a32a4321331703186313232eb339730b1309e317c3194

MNS G8 IN10 N1 O2.00 Y0.00 C0.00 YT0 CT0 s0 sY0.00 S0 C0 FM4 FC000000000:zzzzzz0 c162 0278044079c3f65883c014c0 bac ee202 52 5c34426832c 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 032c315831514b153 0321315e31514b153 03123146313f4b1 b 0317311b311a4b1b1 031c3121311f4b153 03213130312e4b153 0326314731434b153 032b3158315c4b153 03303167317a4b153 03353176318c4b153 033a317f318a4b153 0335317c31864b153 0 8 b 6 8 e14 5 8 3 5 6 8 7 4 a c 6 8 3 4 7 8 2 4171c c132129141e 8 5 612141b f14 7 9 5 7 d11 f131d36171d181e131b1b2412191d261f2b c10 b f161e151d3141311931533094306230893081309930a2304d306b3049320e316a32983192309a30a6322031e330d93100319131a23422327131f731613164311232bd334330a53096315a318530df311131633096307a308a30b630c630a13052306a304d323e3175328e3183309530ab321b31e930ef30f9319e31ad347e329f321a3159316631193298332930a7309b315a317a30c7310731603091306e308930d330c7309e304f306b304b322f316532573166309130ae31f031cf30ea30ea318e31853461327031f13142312c30ef323232ab3098308b312a315d30a930ea3159308430643082306e30b43095304d3069304831f6314131ff313a308230a731a6319730d630cd315b31483424321c31bc311d30e930c631b132053084308130fd312f30ad30ed317f308830603084306030a23099304e3067304a31fb31523210313b308130aa31b3319d30d230cc316131523453321d31c2312830ef30c931b43214308730843100313630bc30f931a630933064308d3055309d30a23051306d304b32153161322f314d307330c631ce31b230d030d7316f315a348f324031d8313d30fd30d131dc3244308930893111314530cb310131c9309c30703097305330ad309e3057306b30503227317232613162306430e931f331cd30c730e03184317834da326231f7315d312030ec321f329a309830903128315e30d7310731d6309d3074309f305230be309c30573069304e322a31803299317030603128320d31dd30c130ed3195318b35093284320b3171313e30ff325532e030a330993143316930da310031cd309930753098304a30c03093304e305e30443230318532b5318c3058316e322e31f230be30ef319d319b3537329f321b3185316a311a329a334830a03093315e317630e930ff31cd309730833099304a30bb3093304f305e30453234319a32dd31b23058318b324a320430cf30f631a131a7354b32aa322f31923187313032cd338930af309a3173318d30f330f831c2309a30863096304c30ed30963051305e3045323c31aa331331da3059317c325331ff30d330fd31aa31b1355532ae32233186319c313632ee33b630b330a5317d319c30f830f631b6309e30953097305030ea309530563062304c322f31b2331731dd305d317e324331fb30d730fc31a531ab355a32a4321331703186313232eb339730b1309e317c3194

MNS G8 IN10 N1 O2.00 Y0.00 C0.00 YT0 CT0 s0 sY0.00 S0 C0 FM4 FC000000000:zzzzzz0 c162 0278044079c3f65883c014c0 bac ee202 52 5c34426832c 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 032c315831514b153 0321315e31514b153 03123146313f4b1 b 0317311b311a4b1b1 031c3121311f4b153 03213130312e4b153 0326314731434b153 032b3158315c4b153 03303167317a4b153 03353176318c4b153 033a317f318a4b153 0335317c31864b153 0 8 b 6 8 e14 5 8 3 5 6 8 7 4 a c 6 8 3 4 7 8 2 4171c c132129141e 8 5 612141b f14 7 9 5 7 d11 f131d36171d181e131b1b2412191d261f2b c10 b f161e151d3141311931533094306230893081309930a2304d306b3049320e316a32983192309a30a6322031e330d93100319131a23422327131f731613164311232bd334330a53096315a318530df311131633096307a308a30b630c630a13052306a304d323e3175328e3183309530ab321b31e930ef30f9319e31ad347e329f321a3159316631193298332930a7309b315a317a30c7310731603091306e308930d330c7309e304f306b304b322f316532573166309130ae31f031cf30ea30ea318e31853461327031f13142312c30ef323232ab3098308b312a315d30a930ea3159308430643082306e30b43095304d3069304831f6314131ff313a308230a731a6319730d630cd315b31483424321c31bc311d30e930c631b132053084308130fd312f30ad30ed317f308830603084306030a23099304e3067304a31fb31523210313b308130aa31b3319d30d230cc316131523453321d31c2312830ef30c931b43214308730843100313630bc30f931a630933064308d3055309d30a23051306d304b32153161322f314d307330c631ce31b230d030d7316f315a348f324031d8313d30fd30d131dc3244308930893111314530cb310131c9309c30703097305330ad309e3057306b30503227317232613162306430e931f331cd30c730e03184317834da326231f7315d312030ec321f329a309830903128315e30d7310731d6309d3074309f305230be309c30573069304e322a31803299317030603128320d31dd30c130ed3195318b35093284320b3171313e30ff325532e030a330993143316930da310031cd309930753098304a30c03093304e305e30443230318532b5318c3058316e322e31f230be30ef319d319b3537329f321b3185316a311a329a334830a03093315e317630e930ff31cd309730833099304a30bb3093304f305e30453234319a32dd31b23058318b324a320430cf30f631a131a7354b32aa322f31923187313032cd338930af309a3173318d30f330f831c2309a30863096304c30ed30963051305e3045323c31aa331331da3059317c325331ff30d330fd31aa31b1355532ae32233186319c313632ee33b630b330a5317d319c30f830f631b6309e30953097305030ea309530563062304c322f31b2331731dd305d317e324331fb30d730fc31a531ab355a32a4321331703186313232eb339730b1309e317c3194

MNS G8 IN10 N1 O2.00 Y0.00 C0.00 YT0 CT0 s0 sY0.00 S0 C0 FM0 FC010000011:zzzzzz1 b166 02780440117a51416616814c0 bac ee202 52 5c34b26f333 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 031f3117312b4b150 03153117312b4b14f 030b3117312b4b1 b 03013117312b4b1b8 030d3117312b4b150 03113117312b4b150 03153117312b4b150 03193117312b4b150 031d3117312b4b150 03193117312b4b150 03193117312b4b150 0 8 a 9 6 8 d c 6 5 c a b b f 5 e d 511 5 6 5 6 3 713 f 7 8261219 e d 7 f111a 717 4 9 3 5 418 414 e2c133233222829182118151533142918141314132a1b2d21fc20ce226120b120bb20a9218c216f207e208a208720722218208c256f22c520f3219b23bb2314214c213922a022492624232c23a323db2228214a265c234b21392197231022d721fc20ce226120b120bb20a9218c216f207e208a208720722218208c256f22c520f3219b23bb2314214c213922a022492624232c23a323db2228214a265c234b21392197231022d721fc20ce226120b120bb20a9218c216f207e208a208720722218208c256f22c520f3219b23bb2314214c213922a022492624232c23a323db2228214a265c234b21392197231022d721fc20ce226120b120bb20a9218c216f207e208a208720722218208c256f22c520f3219b23bb2314214c213922a022492624232c23a323db2228214a265c234b21392197231022d721fc20ce226120b120bb20a9218c216f207e208a208720722218208c256f22c520f3219b23bb2314214c213922a022492624232c23a323db2228214a265c234b21392197231022d721fc20ce226120b120bb20a9218c216f207e208a208720722218208c256f22c520f3219b23bb2314214c213922a022492624232c23a323db2228214a265c234b21392197231022d721fc20ce226120b120bb20a9218c216f207e208a208720722218208c256f22c520f3219b23bb2314214c213922a022492624232c23a323db2228214a265c234b21392197231022d721fc20ce226120b120bb20a9218c216f207e208a208720722218208c256f22c520f3219b23bb2314214c213922a022492624232c23a323db2228214a265c234b21392197231022d721fc20ce226120b120bb20a9218c216f207e208a208720722218208c256f22c520f3219b23bb2314214c213922a022492624232c23a323db2228214a265c234b21392197231022d721fc20ce226120b120bb20a9218c216f207e208a208720722218208c256f22c520f3219b23bb2314214c213922a022492624232c23a323db2228214a265c234b21392197231022d721fc20ce226120b120bb20a9218c216f207e208a208720722218208c256f22c520f3219b23bb2314214c213922a022492624232c23a323db2228214a265c234b21392197231022d7

MNS G8 IN10 N1 O2.00 Y0.00 C0.00 YT0 CT0 s0 sY0.00 S0 C0 FM4 FC000000000:zzzzzz0 b165 0278044079c3f65883c014c0 bac ee202 52 5c34726b32f 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 032f21b2216d4b150 031f221921a14b150 031021df21874b1 b 031721a8216f4b1b8 031e21bc217d4b151 032521db218e4b151 032c21ec21974b151 0333221121ac4b151 033a223221bd4b151 0341223f21c14b151 033a222921ba4b151 0 e11 a b 9 a 9 a 7 8 8 a a b a c 4 5 4 4 6 8 4 4 b11 6 7212f 8 a b c d e e111519 6 7 3 4141811142d37272f222720231c22101223291a2010131012181d191e3111316d306a30cc304c305430873090305730b63052303730a03095319f3067305e306730f43121303f3033310430dd33183153328c312a310630e5310230ce30a630a330f430ff314e31c530793104305030593096309c306430da305b303a30c13098320a307e3068306c31163157304430353147312833d231ce33223197315b310431a7313530c930bb3130312c312b318b306f30ff3051305530923094305a30be3056303930be308231e030763063306b3104313c30423034312330f8337c317f32cc3150312530f3313e30f630b230ab3111311430ee314b306730f9304c3056308c308f305630963055303630ba307031a9306f3060306730fa311d3041303430f830d732f831413286311d30f930e130ea30c330a530a230f130fd30fa315a30653108304e305730913096305830953058303830c6306f31c33076306130693106312a30403034310630e93324315332a3312c310330e5310430d230a530a3310031073110317c306f311b304f305a30933097305a309b305a303730d3307031e8307f3062306b3112313d30413036311c31023367317232d93147311630ef312c30ed30a930aa31143113311d318d30723128304f305a3098309e305c309e305e303b30db306d320230853061306a311a314930433039312f31113388318432e63152311e30f0314430fd30ac30a93121311e313b31b1307531433052305d309d30a0306030a23061303c30ec306d322630933063306b3130315a304430393149313533d031b0330a3171313730f63181312730b230ae3139312c315331d0307c31543051305f30a030a1305f30a63065303f30fa30703256309f3062306e3140316a3046303a315b314d341531df33303195315230fd31b9314730b930b4314b3139316531d8307a31583053305d30a030a5305f30a53064303e3100306f327130a53062306e3144316d3046303d31663152344e31e83341319a315430fa31c2314e30b830b831543141316c31c0307d31493052305c309b30a4305d30a83062303e3103306e325e30a43062306d314031643044303a31533143344731c733373173313030ed318a312a30ad30ae3144313b

MNS G7 IN10 N1 O2.00 Y0.00 C0.00 YT0 CT0 s0 sY0.00 S0 C0 FM5 FC000000000:zzzzzz0 b164 0278044079c3f65883c014c0 bac ee202 52 5c34726b32f 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 032f21b2216d4b150 031f221921a14b150 031021df21874b1 b 031721a8216f4b1b8 031e21bc217d4b151 032521db218e4b151 032c21ec21974b151 0333221121ac4b151 033a223221bd4b151 0341223f21c14b151 033a222921ba4b151 0 e11 a b 9 a 9 a 7 8 8 a a b a c 4 5 4 4 6 8 4 4 b11 6 7212f 8 a b c d e e111519 6 7 3 4141811142d37272f222720231c22101223291a2010131012181d191e3111316d306a30cc304c305430873090305730b63052303730a03095319f3067305e306730f43121303f3033310430dd33183153328c312a310630e5310230ce30a630a330f430ff314e31c530793104305030593096309c306430da305b303a30c13098320a307e3068306c31163157304430353147312833d231ce33223197315b310431a7313530c930bb3130312c312b318b306f30ff3051305530923094305a30be3056303930be308231e030763063306b3104313c30423034312330f8337c317f32cc3150312530f3313e30f630b230ab3111311430ee314b306730f9304c3056308c308f305630963055303630ba307031a9306f3060306730fa311d3041303430f830d732f831413286311d30f930e130ea30c330a530a230f130fd30fa315a30653108304e305730913096305830953058303830c6306f31c33076306130693106312a30403034310630e93324315332a3312c310330e5310430d230a530a3310031073110317c306f311b304f305a30933097305a309b305a303730d3307031e8307f3062306b3112313d30413036311c31023367317232d93147311630ef312c30ed30a930aa31143113311d318d30723128304f305a3098309e305c309e305e303b30db306d320230853061306a311a314930433039312f31113388318432e63152311e30f0314430fd30ac30a93121311e313b31b1307531433052305d309d30a0306030a23061303c30ec306d322630933063306b3130315a304430393149313533d031b0330a3171313730f63181312730b230ae3139312c315331d0307c31543051305f30a030a1305f30a63065303f30fa30703256309f3062306e3140316a3046303a315b314d341531df33303195315230fd31b9314730b930b4314b3139316531d8307a31583053305d30a030a5305f30a53064303e3100306f327130a53062306e3144316d3046303d31663152344e31e83341319a315430fa31c2314e30b830b831543141316c31c0307d31493052305c309b30a4305d30a83062303e3103306e325e30a43062306d314031643044303a31533143344731c733373173313030ed318a312a30ad30ae3144313b

MNS G7 IN10 N1 O2.00 Y0.00 C0.00 YT0 CT0 s0 sY0.00 S0 C0 FM4 FC000000000:zzzzzz0 c164 0278044079c3f65883c014c0 bac ee202 52 5c34426832c 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 032c315831514b153 0321315e31514b153 03123146313f4b1 b 0317311b311a4b1b1 031c3121311f4b153 03213130312e4b153 0326314731434b153 032b3158315c4b153 03303167317a4b153 03353176318c4b153 033a317f318a4b153 0335317c31864b153 0 8 b 6 8 e14 5 8 3 5 6 8 7 4 a c 6 8 3 4 7 8 2 4171c c132129141e 8 5 612141b f14 7 9 5 7 d11 f131d36171d181e131b1b2412191d261f2b c10 b f161e151d3141311931533094306230893081309930a2304d306b3049320e316a32983192309a30a6322031e330d93100319131a23422327131f731613164311232bd334330a53096315a318530df311131633096307a308a30b630c630a13052306a304d323e3175328e3183309530ab321b31e930ef30f9319e31ad347e329f321a3159316631193298332930a7309b315a317a30c7310731603091306e308930d330c7309e304f306b304b322f316532573166309130ae31f031cf30ea30ea318e31853461327031f13142312c30ef323232ab3098308b312a315d30a930ea3159308430643082306e30b43095304d3069304831f6314131ff313a308230a731a6319730d630cd315b31483424321c31bc311d30e930c631b132053084308130fd312f30ad30ed317f308830603084306030a23099304e3067304a31fb31523210313b308130aa31b3319d30d230cc316131523453321d31c2312830ef30c931b43214308730843100313630bc30f931a630933064308d3055309d30a23051306d304b32153161322f314d307330c631ce31b230d030d7316f315a348f324031d8313d30fd30d131dc3244308930893111314530cb310131c9309c30703097305330ad309e3057306b30503227317232613162306430e931f331cd30c730e03184317834da326231f7315d312030ec321f329a309830903128315e30d7310731d6309d3074309f305230be309c30573069304e322a31803299317030603128320d31dd30c130ed3195318b35093284320b3171313e30ff325532e030a330993143316930da310031cd309930753098304a30c03093304e305e30443230318532b5318c3058316e322e31f230be30ef319d319b3537329f321b3185316a311a329a334830a03093315e317630e930ff31cd309730833099304a30bb3093304f305e30453234319a32dd31b23058318b324a320430cf30f631a131a7354b32aa322f31923187313032cd338930af309a3173318d30f330f831c2309a30863096304c30ed30963051305e3045323c31aa331331da3059317c325331ff30d330fd31aa31b1355532ae32233186319c313632ee33b630b330a5317d319c30f830f631b6309e30953097305030ea309530563062304c322f31b2331731dd305d317e324331fb30d730fc31a531ab355a32a4321331703186313232eb339730b1309e317c3194

MNS G8 IN10 N1 O2.00 Y0.00 C0.00 YT0 CT0 s0 sY0.00 S0 C0 FM4 FC000000000:zzzzzz0 c162 0278044079c3f65883c014c0 bac ee202 52 5c34426832c 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 032c315831514b153 0321315e31514b153 03123146313f4b1 b 0317311b311a4b1b1 031c3121311f4b153 03213130312e4b153 0326314731434b153 032b3158315c4b153 03303167317a4b153 03353176318c4b153 033a317f318a4b153 0335317c31864b153 0 8 b 6 8 e14 5 8 3 5 6 8 7 4 a c 6 8 3 4 7 8 2 4171c c132129141e 8 5 612141b f14 7 9 5 7 d11 f131d36171d181e131b1b2412191d261f2b c10 b f161e151d3141311931533094306230893081309930a2304d306b3049320e316a32983192309a30a6322031e330d93100319131a23422327131f731613164311232bd334330a53096315a318530df311131633096307a308a30b630c630a13052306a304d323e3175328e3183309530ab321b31e930ef30f9319e31ad347e329f321a3159316631193298332930a7309b315a317a30c7310731603091306e308930d330c7309e304f306b304b322f316532573166309130ae31f031cf30ea30ea318e31853461327031f13142312c30ef323232ab3098308b312a315d30a930ea3159308430643082306e30b43095304d3069304831f6314131ff313a308230a731a6319730d630cd315b31483424321c31bc311d30e930c631b132053084308130fd312f30ad30ed317f308830603084306030a23099304e3067304a31fb31523210313b308130aa31b3319d30d230cc316131523453321d31c2312830ef30c931b43214308730843100313630bc30f931a630933064308d3055309d30a23051306d304b32153161322f314d307330c631ce31b230d030d7316f315a348f324031d8313d30fd30d131dc3244308930893111314530cb310131c9309c30703097305330ad309e3057306b30503227317232613162306430e931f331cd30c730e03184317834da326231f7315d312030ec321f329a309830903128315e30d7310731d6309d3074309f305230be309c30573069304e322a31803299317030603128320d31dd30c130ed3195318b35093284320b3171313e30ff325532e030a330993143316930da310031cd309930753098304a30c03093304e305e30443230318532b5318c3058316e322e31f230be30ef319d319b3537329f321b3185316a311a329a334830a03093315e317630e930ff31cd309730833099304a30bb3093304f305e30453234319a32dd31b23058318b324a320430cf30f631a131a7354b32aa322f31923187313032cd338930af309a3173318d30f330f831c2309a30863096304c30ed30963051305e3045323c31aa331331da3059317c325331ff30d330fd31aa31b1355532ae32233186319c313632ee33b630b330a5317d319c30f830f631b6309e30953097305030ea309530563062304c322f31b2331731dd305d317e324331fb30d730fc31a531ab355a32a4321331703186313232eb339730b1309e317c3194

MNS G8 IN10 N1 O2.00 Y0.00 C0.00 YT0 CT0 s0 sY0.00 S0 C0 FM4 FC000000000:zzzzzz0 c162 0278044079c3f65883c014c0 bac ee202 52 5c34426832c 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 032c315831514b153 0321315e31514b153 03123146313f4b1 b 0317311b311a4b1b1 031c3121311f4b153 03213130312e4b153 0326314731434b153 032b3158315c4b153 03303167317a4b153 03353176318c4b153 033a317f318a4b153 0335317c31864b153 0 8 b 6 8 e14 5 8 3 5 6 8 7 4 a c 6 8 3 4 7 8 2 4171c c132129141e 8 5 612141b f14 7 9 5 7 d11 f131d36171d181e131b1b2412191d261f2b c10 b f161e151d3141311931533094306230893081309930a2304d306b3049320e316a32983192309a30a6322031e330d93100319131a23422327131f731613164311232bd334330a53096315a318530df311131633096307a308a30b630c630a13052306a304d323e3175328e3183309530ab321b31e930ef30f9319e31ad347e329f321a3159316631193298332930a7309b315a317a30c7310731603091306e308930d330c7309e304f306b304b322f316532573166309130ae31f031cf30ea30ea318e31853461327031f13142312c30ef323232ab3098308b312a315d30a930ea3159308430643082306e30b43095304d3069304831f6314131ff313a308230a731a6319730d630cd315b31483424321c31bc311d30e930c631b132053084308130fd312f30ad30ed317f308830603084306030a23099304e3067304a31fb31523210313b308130aa31b3319d30d230cc316131523453321d31c2312830ef30c931b43214308730843100313630bc30f931a630933064308d3055309d30a23051306d304b32153161322f314d307330c631ce31b230d030d7316f315a348f324031d8313d30fd30d131dc3244308930893111314530cb310131c9309c30703097305330ad309e3057306b30503227317232613162306430e931f331cd30c730e03184317834da326231f7315d312030ec321f329a309830903128315e30d7310731d6309d3074309f305230be309c30573069304e322a31803299317030603128320d31dd30c130ed3195318b35093284320b3171313e30ff325532e030a330993143316930da310031cd309930753098304a30c03093304e305e30443230318532b5318c3058316e322e31f230be30ef319d319b3537329f321b3185316a311a329a334830a03093315e317630e930ff31cd309730833099304a30bb3093304f305e30453234319a32dd31b23058318b324a320430cf30f631a131a7354b32aa322f31923187313032cd338930af309a3173318d30f330f831c2309a30863096304c30ed30963051305e3045323c31aa331331da3059317c325331ff30d330fd31aa31b1355532ae32233186319c313632ee33b630b330a5317d319c30f830f631b6309e30953097305030ea309530563062304c322f31b2331731dd305d317e324331fb30d730fc31a531ab355a32a4321331703186313232eb339730b1309e317c3194

MNS G8 IN10 N1 O2.00 Y0.00 C0.00 YT0 CT0 s0 sY0.00 S0 C0 FM0 FC010000011:zzzzzz1 b166 02780440117a51416616814c0 bac ee202 52 5c34b26f333 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 031f3117312b4b150 03153117312b4b14f 030b3117312b4b1 b 03013117312b4b1b8 030d3117312b4b150 03113117312b4b150 03153117312b4b150 03193117312b4b150 031d3117312b4b150 03193117312b4b150 03193117312b4b150 0 8 a 9 6 8 d c 6 5 c a b b f 5 e d 511 5 6 5 6 3 713 f 7 8261219 e d 7 f111a 717 4 9 3 5 418 414 e2c133233222829182118151533142918141314132a1b2d21fc20ce226120b120bb20a9218c216f207e208a208720722218208c256f22c520f3219b23bb2314214c213922a022492624232c23a323db2228214a265c234b21392197231022d721fc20ce226120b120bb20a9218c216f207e208a208720722218208c256f22c520f3219b23bb2314214c213922a022492624232c23a323db2228214a265c234b21392197231022d721fc20ce226120b120bb20a9218c216f207e208a208720722218208c256f22c520f3219b23bb2314214c213922a022492624232c23a323db2228214a265c234b21392197231022d721fc20ce226120b120bb20a9218c216f207e208a208720722218208c256f22c520f3219b23bb2314214c213922a022492624232c23a323db2228214a265c234b21392197231022d721fc20ce226120b120bb20a9218c216f207e208a208720722218208c256f22c520f3219b23bb2314214c213922a022492624232c23a323db2228214a265c234b21392197231022d721fc20ce226120b120bb20a9218c216f207e208a208720722218208c256f22c520f3219b23bb2314214c213922a022492624232c23a323db2228214a265c234b21392197231022d721fc20ce226120b120bb20a9218c216f207e208a208720722218208c256f22c520f3219b23bb2314214c213922a022492624232c23a323db2228214a265c234b21392197231022d721fc20ce226120b120bb20a9218c216f207e208a208720722218208c256f22c520f3219b23bb2314214c213922a022492624232c23a323db2228214a265c234b21392197231022d721fc20ce226120b120bb20a9218c216f207e208a208720722218208c256f22c520f3219b23bb2314214c213922a022492624232c23a323db2228214a265c234b21392197231022d721fc20ce226120b120bb20a9218c216f207e208a208720722218208c256f22c520f3219b23bb2314214c213922a022492624232c23a323db2228214a265c234b21392197231022d721fc20ce226120b120bb20a9218c216f207e208a208720722218208c256f22c520f3219b23bb2314214c213922a022492624232c23a323db2228214a265c234b21392197231022d7

MNS G8 IN10 N1 O2.00 Y0.00 C0.00 YT0 CT0 s0 sY0.00 S0 C0 FM4 FC000000000:zzzzzz0 b165 0278044079c3f65883c014c0 bac ee202 52 5c34726b32f 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 032f21b2216d4b150 031f221921a14b150 031021df21874b1 b 031721a8216f4b1b8 031e21bc217d4b151 032521db218e4b151 032c21ec21974b151 0333221121ac4b151 033a223221bd4b151 0341223f21c14b151 033a222921ba4b151 0 e11 a b 9 a 9 a 7 8 8 a a b a c 4 5 4 4 6 8 4 4 b11 6 7212f 8 a b c d e e111519 6 7 3 4141811142d37272f222720231c22101223291a2010131012181d191e3111316d306a30cc304c305430873090305730b63052303730a03095319f3067305e306730f43121303f3033310430dd33183153328c312a310630e5310230ce30a630a330f430ff314e31c530793104305030593096309c306430da305b303a30c13098320a307e3068306c31163157304430353147312833d231ce33223197315b310431a7313530c930bb3130312c312b318b306f30ff3051305530923094305a30be3056303930be308231e030763063306b3104313c30423034312330f8337c317f32cc3150312530f3313e30f630b230ab3111311430ee314b306730f9304c3056308c308f305630963055303630ba307031a9306f3060306730fa311d3041303430f830d732f831413286311d30f930e130ea30c330a530a230f130fd30fa315a30653108304e305730913096305830953058303830c6306f31c33076306130693106312a30403034310630e93324315332a3312c310330e5310430d230a530a3310031073110317c306f311b304f305a30933097305a309b305a303730d3307031e8307f3062306b3112313d30413036311c31023367317232d93147311630ef312c30ed30a930aa31143113311d318d30723128304f305a3098309e305c309e305e303b30db306d320230853061306a311a314930433039312f31113388318432e63152311e30f0314430fd30ac30a93121311e313b31b1307531433052305d309d30a0306030a23061303c30ec306d322630933063306b3130315a304430393149313533d031b0330a3171313730f63181312730b230ae3139312c315331d0307c31543051305f30a030a1305f30a63065303f30fa30703256309f3062306e3140316a3046303a315b314d341531df33303195315230fd31b9314730b930b4314b3139316531d8307a31583053305d30a030a5305f30a53064303e3100306f327130a53062306e3144316d3046303d31663152344e31e83341319a315430fa31c2314e30b830b831543141316c31c0307d31493052305c309b30a4305d30a83062303e3103306e325e30a43062306d314031643044303a31533143344731c733373173313030ed318a312a30ad30ae3144313b

MNS G7 IN10 N1 O2.00 Y0.00 C0.00 YT0 CT0 s0 sY0.00 S0 C0 FM5 FC000000000:zzzzzz0 b164 0278044079c3f65883c014c0 bac ee202 52 5c34726b32f 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 032f21b2216d4b150 031f221921a14b150 031021df21874b1 b 031721a8216f4b1b8 031e21bc217d4b151 032521db218e4b151 032c21ec21974b151 0333221121ac4b151 033a223221bd4b151 0341223f21c14b151 033a222921ba4b151 0 e11 a b 9 a 9 a 7 8 8 a a b a c 4 5 4 4 6 8 4 4 b11 6 7212f 8 a b c d e e111519 6 7 3 4141811142d37272f222720231c22101223291a2010131012181d191e3111316d306a30cc304c305430873090305730b63052303730a03095319f3067305e306730f43121303f3033310430dd33183153328c312a310630e5310230ce30a630a330f430ff314e31c530793104305030593096309c306430da305b303a30c13098320a307e3068306c31163157304430353147312833d231ce33223197315b310431a7313530c930bb3130312c312b318b306f30ff3051305530923094305a30be3056303930be308231e030763063306b3104313c30423034312330f8337c317f32cc3150312530f3313e30f630b230ab3111311430ee314b306730f9304c3056308c308f305630963055303630ba307031a9306f3060306730fa311d3041303430f830d732f831413286311d30f930e130ea30c330a530a230f130fd30fa315a30653108304e305730913096305830953058303830c6306f31c33076306130693106312a30403034310630e93324315332a3312c310330e5310430d230a530a3310031073110317c306f311b304f305a30933097305a309b305a303730d3307031e8307f3062306b3112313d30413036311c31023367317232d93147311630ef312c30ed30a930aa31143113311d318d30723128304f305a3098309e305c309e305e303b30db306d320230853061306a311a314930433039312f31113388318432e63152311e30f0314430fd30ac30a93121311e313b31b1307531433052305d309d30a0306030a23061303c30ec306d322630933063306b3130315a304430393149313533d031b0330a3171313730f63181312730b230ae3139312c315331d0307c31543051305f30a030a1305f30a63065303f30fa30703256309f3062306e3140316a3046303a315b314d341531df33303195315230fd31b9314730b930b4314b3139316531d8307a31583053305d30a030a5305f30a53064303e3100306f327130a53062306e3144316d3046303d31663152344e31e83341319a315430fa31c2314e30b830b831543141316c31c0307d31493052305c309b30a4305d30a83062303e3103306e325e30a43062306d314031643044303a31533143344731c733373173313030ed318a312a30ad30ae3144313b

-

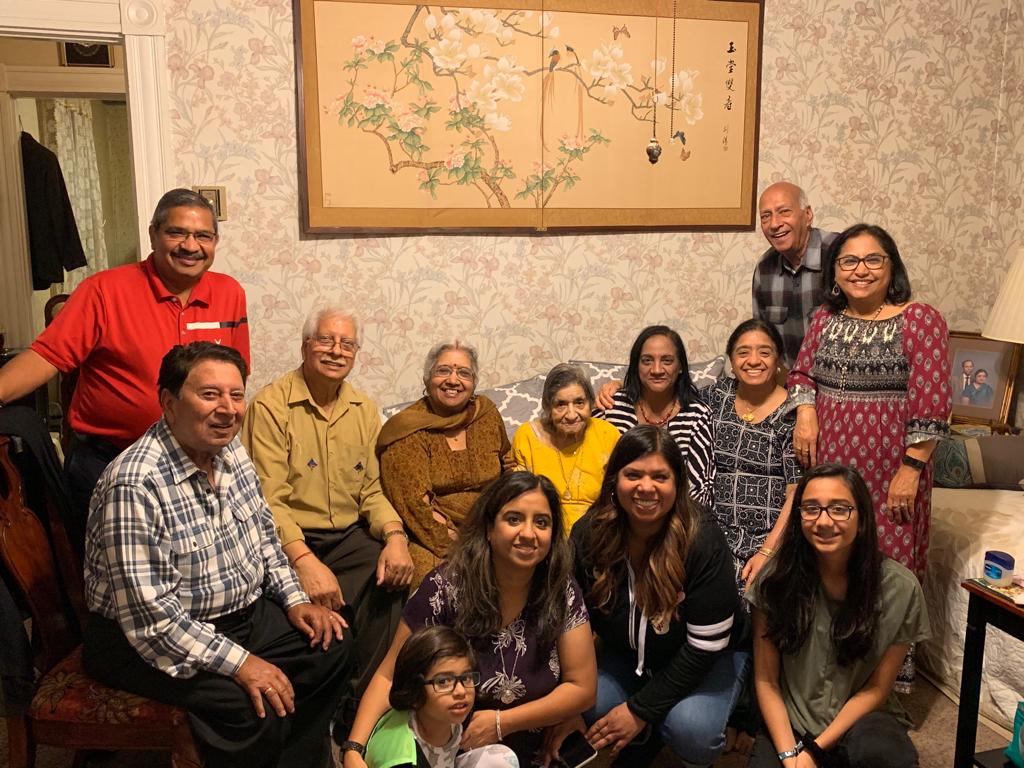

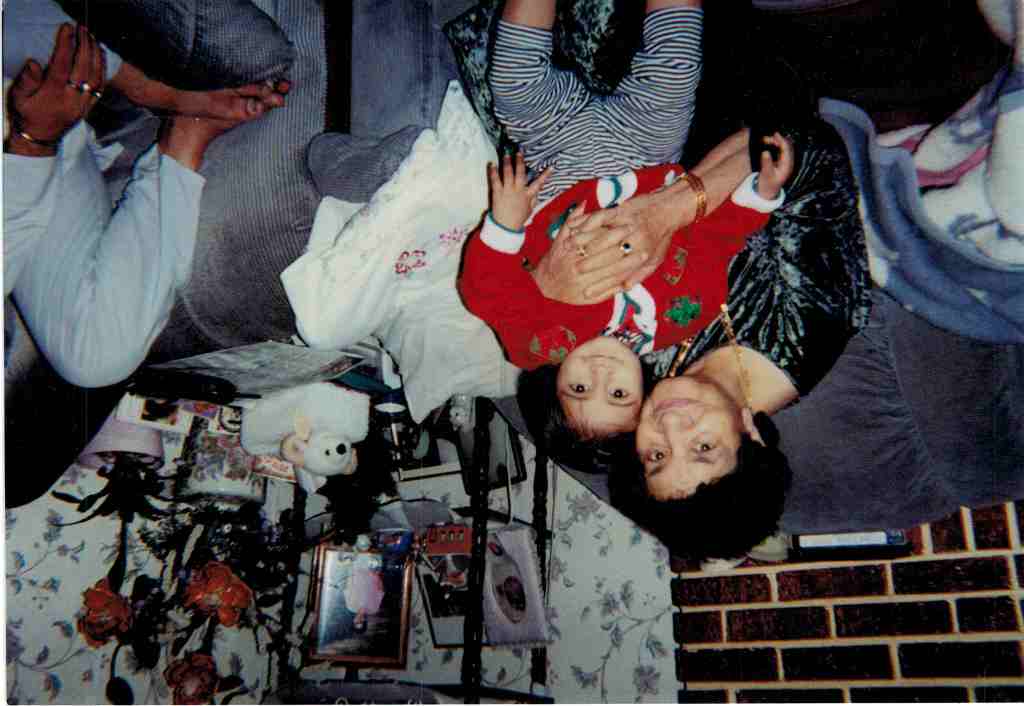

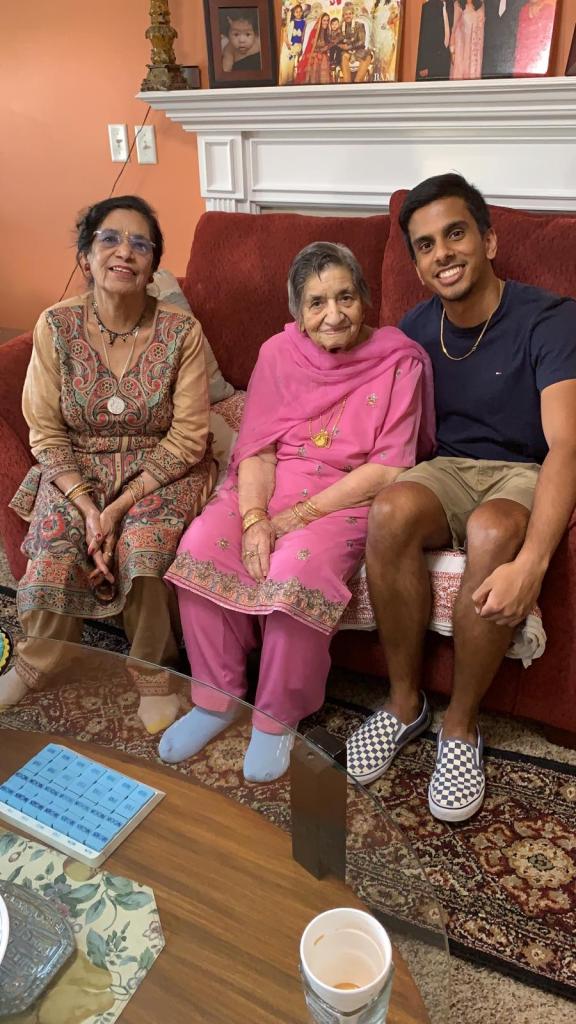

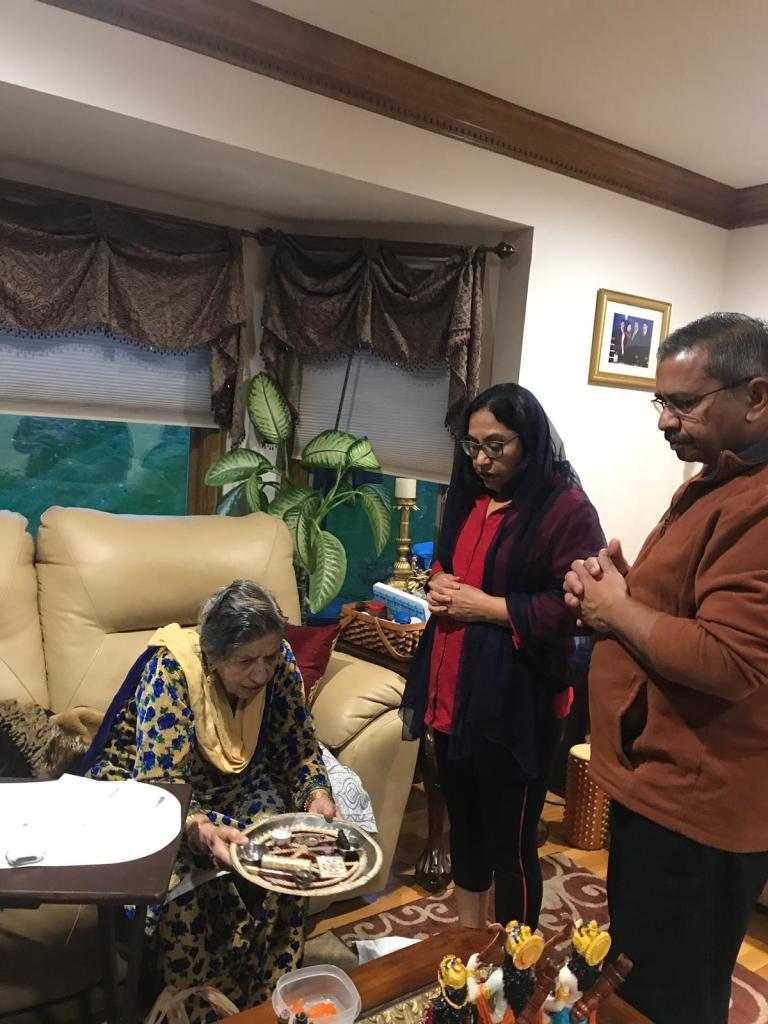

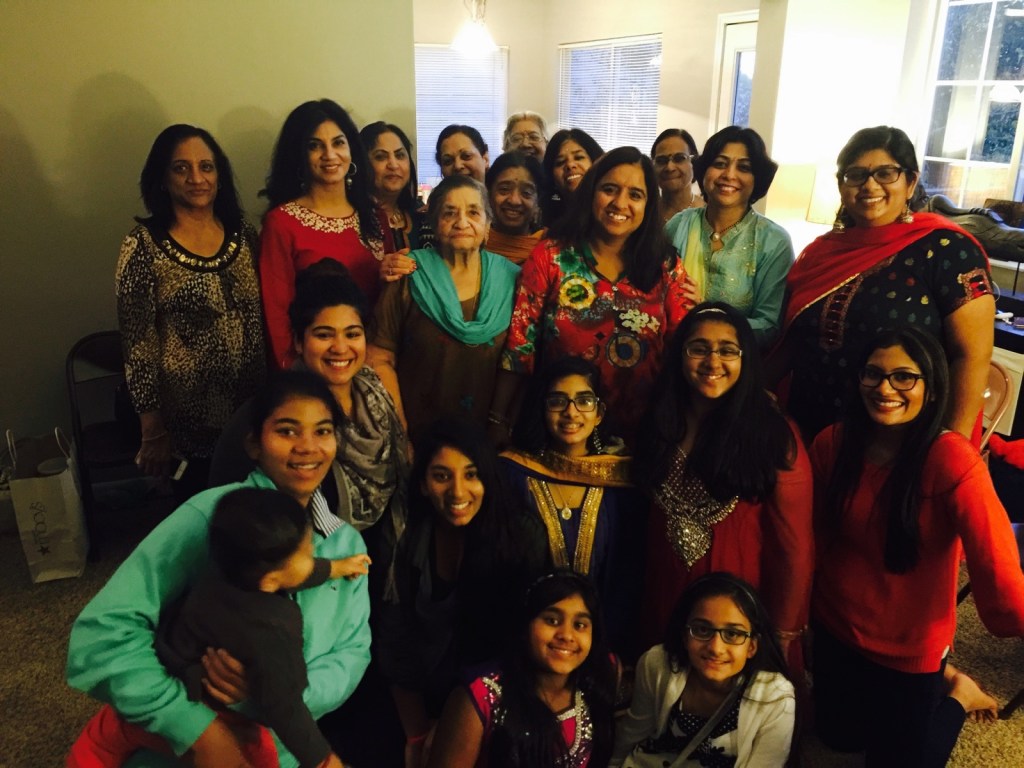

Hello Family!

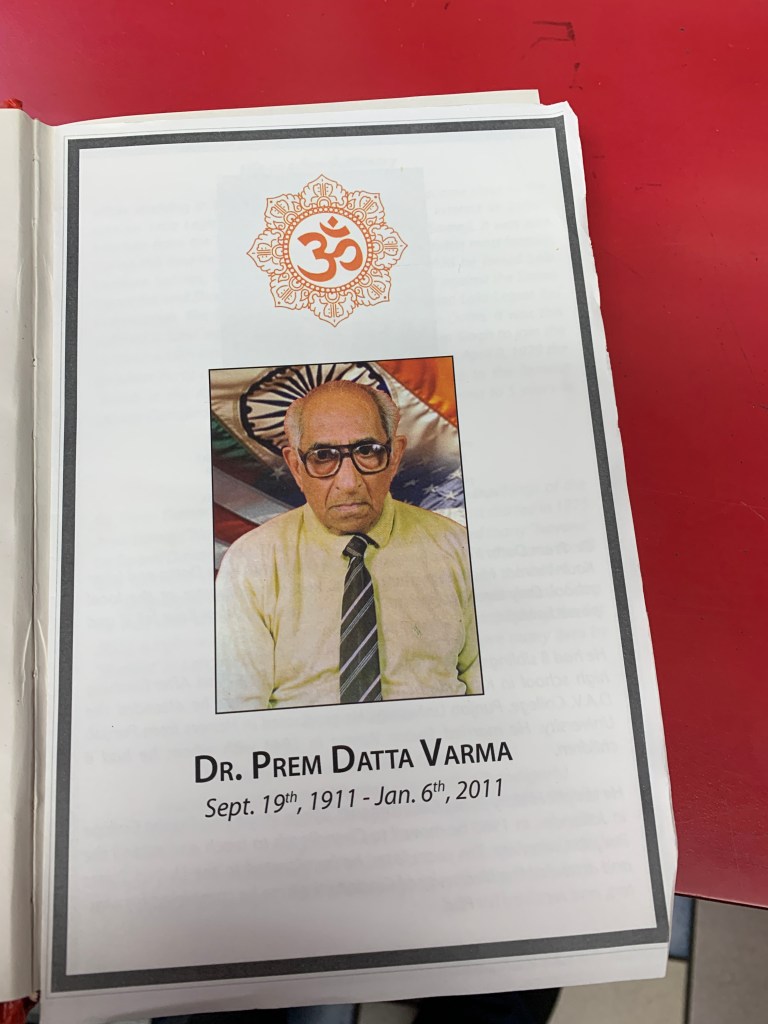

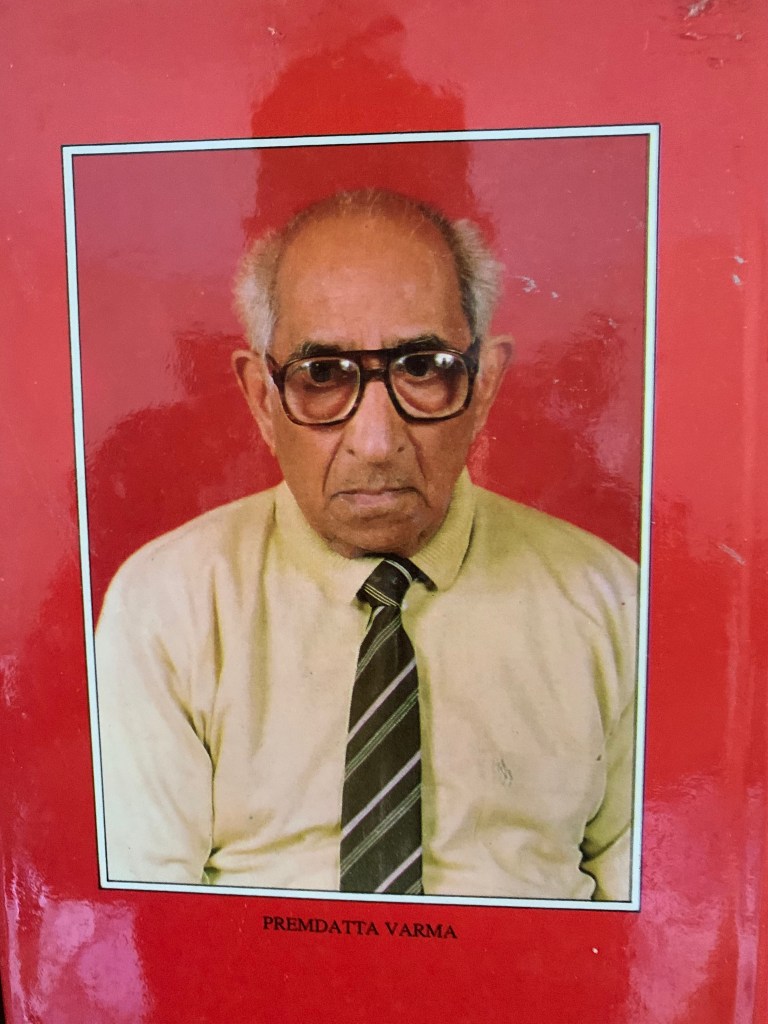

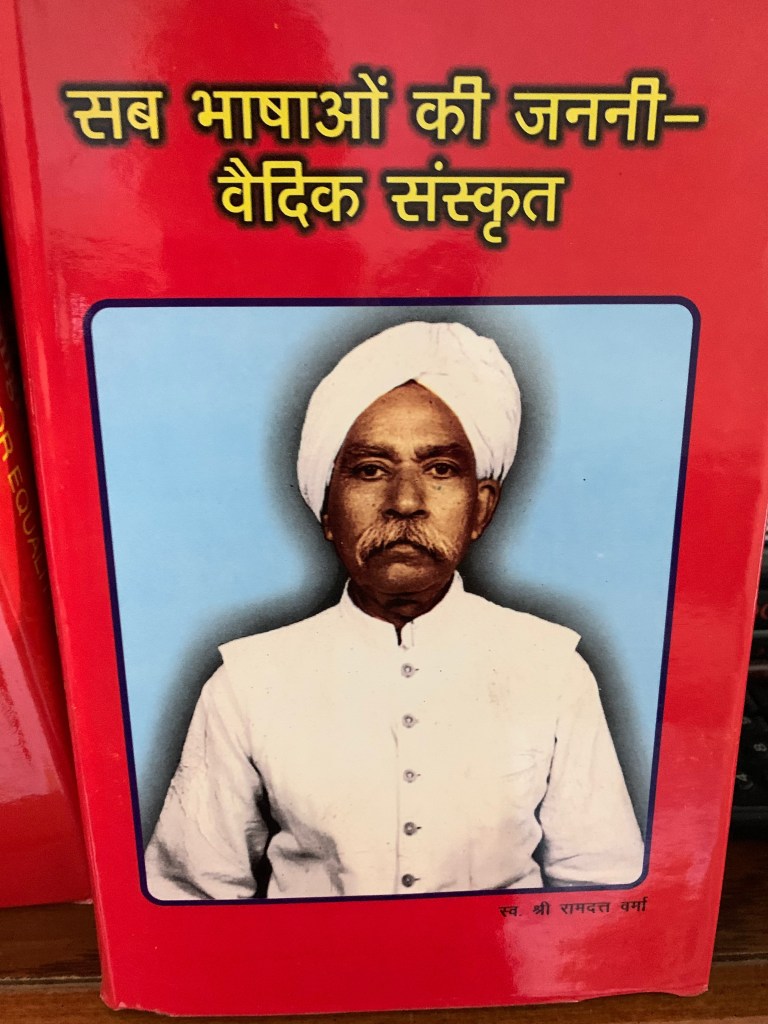

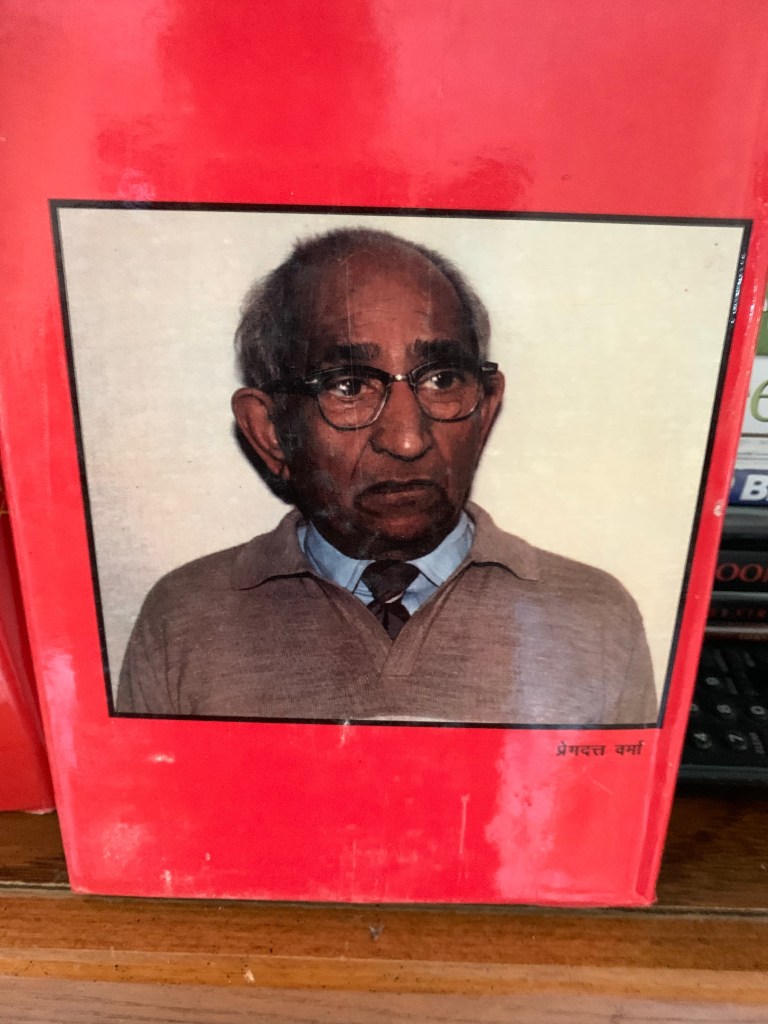

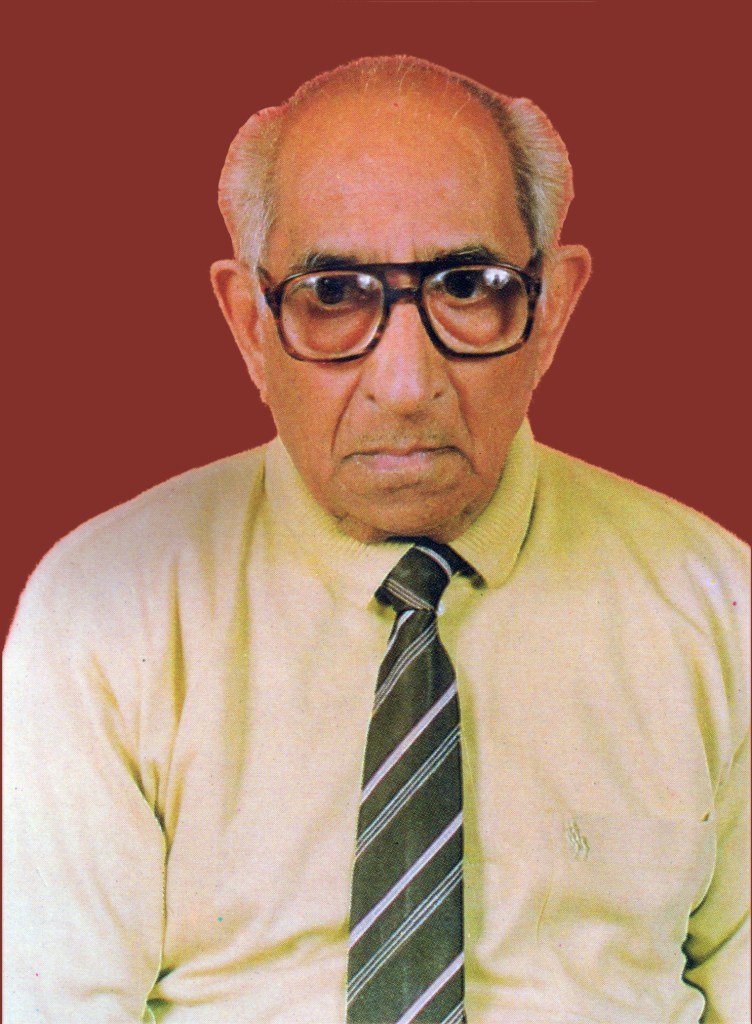

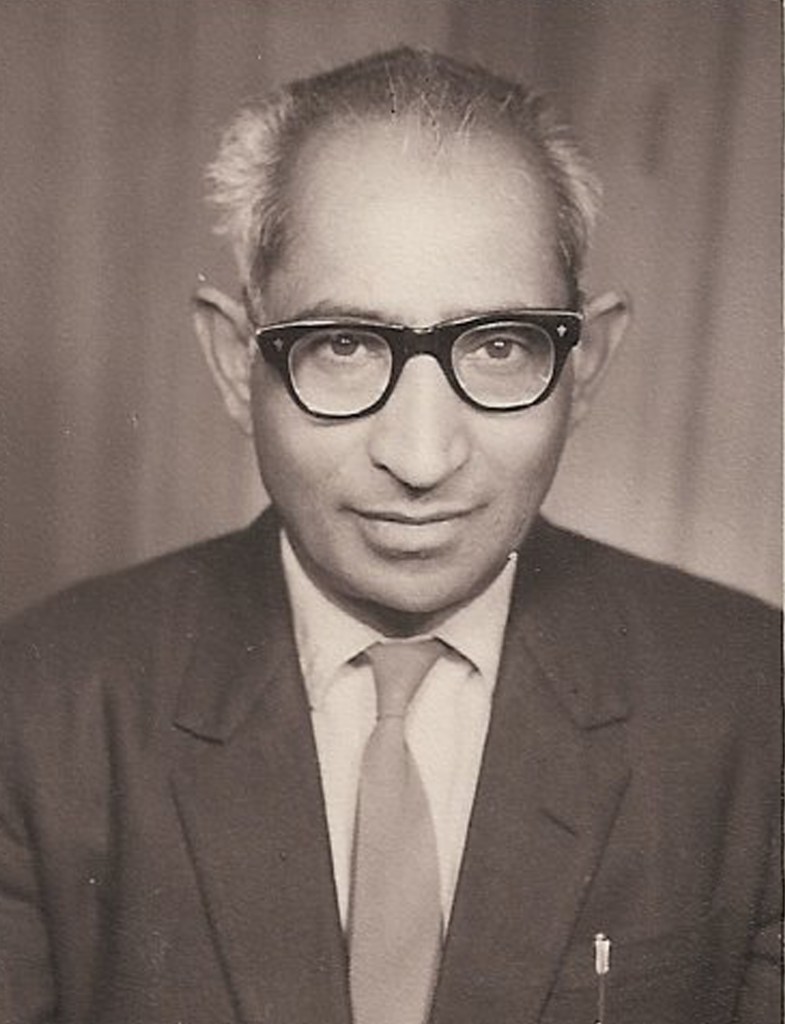

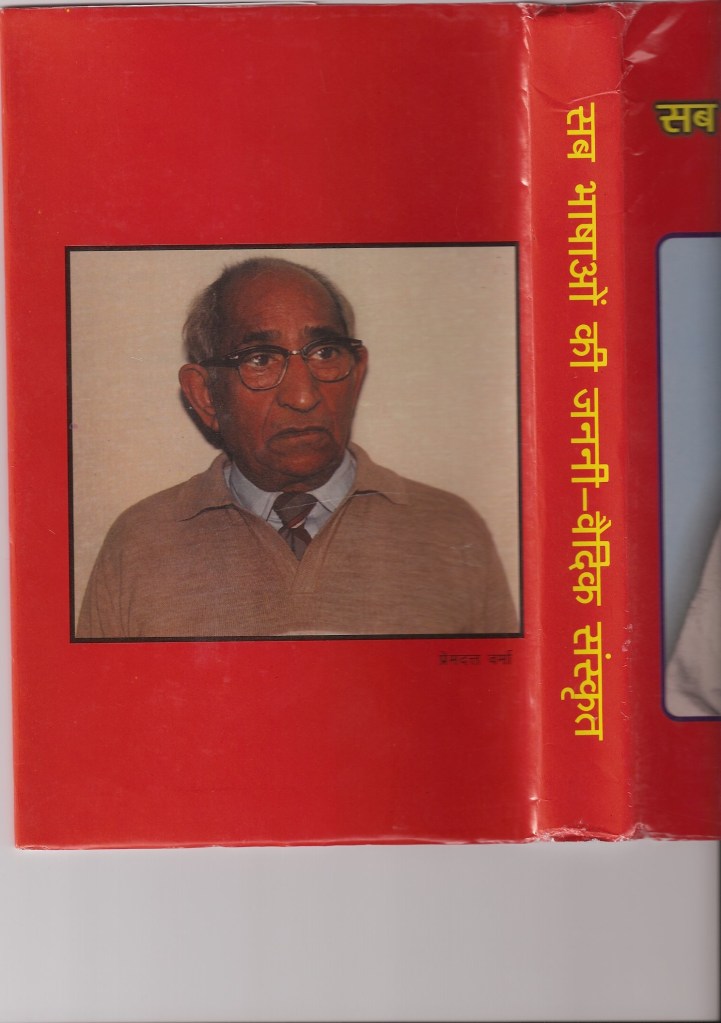

My father, Dr. Prem Datta Varma, was a freedom fighter who spent five years in jail. A friend once asked me why, after such deep devotion to India, he chose to leave for another country. Many people migrate to the United States in search of improved opportunities and a more secure future for their families. My father’s reason was similar, though with some differences.

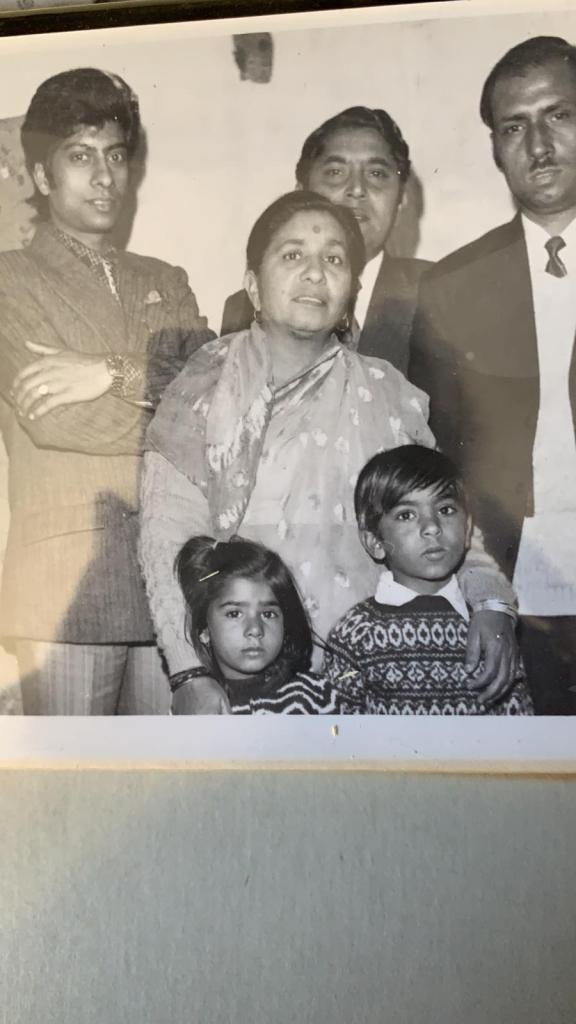

As a history professor at Punjab University in the 1960s, his goal was to research and write a thesis on student freedom fighters during British rule—a group he himself belonged to, made up mostly of college students from Lahore. Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev, and Rajguru, who were sentenced to death in the Lahore Conspiracy Case, were also college students there. My father, then a first-year student at DAV College, Lahore, witnessed these events firsthand.

In 1928, Arya Samaj leader Lala Lajpat Rai organized a protest in Lahore against British rule, which drew massive participation from college students. During the march, British officers Saunders and Scott attacked Lala Lajpat Rai, who was leading the procession, with batons, inflicting injuries that ultimately led to his death. My father, along with many other students, saw this brutality. Deeply shaken, they resolved to avenge their beloved leader’s killing. After careful planning and secretly acquiring a gun, they assassinated Officer Saunders on December 17, 1928, at a police station. (Scott happened to be absent that day.)

The aim of these young revolutionaries was to mobilize students against the illegal British occupation of India. They were ordinary students with no prior experience in organizing political movements against a powerful empire. Sukhdev’s sister, an attorney and activist in Lahore, often visited DAV College’s hostel to inspire students. While Bhagat Singh and his comrades were hiding from the police, new members continued to join their cause. One of those new members was a couple from Calcutta. Mr. Mukherjee was a chemistry professor. He knew how to make a small bomb.

The group later decided to create a non-lethal bomb—designed only to make noise and attract attention, not to injure anyone. They chose the Lahore Assembly as their target. When the assembly was in session, Bhagat Singh and Batukeshwar Dutt threw the bombs, which contained nothing but confetti. No one was harmed. Instead, Singh and Dutt distributed pamphlets, raising slogans like “India Desires Freedom,” to explain their mission.

These actions directly challenge the claim that Bhagat Singh was a Marxist. Can anyone point to a Marxist movement in history that avoided bloodshed? Unlike Marxist revolutions, which caused countless deaths under leaders like Mao Zedong, Karl Marx, and Lenin, Bhagat Singh’s movement sought to awaken people to fight for freedom without indiscriminate violence. Even today, while communist parties are banned in the U.S., a Marxist political party operates openly in India, influencing campuses, labor unions, and farmers’ unions—the three most vulnerable groups to ideological exploitation. Students are often influenced by teachers with biases.

My father was both a history student and later a professor in India. His lifelong aspiration was to pursue doctoral research on the role of Indian college students in the freedom struggle against the British Empire. Having himself served five years in a British prison, he was not just a scholar of the movement but also one of its participants. At the young age of 17, he became a close associate of Bhagat Singh, one of the movement’s most prominent leaders. While Bhagat Singh was eventually executed, my father received a sentence of five years of rigorous imprisonment. This experience gave him a deep, firsthand understanding of the actions, motivations, and philosophy of the student-led resistance.

After his release, my father applied to Punjab University, Chandigarh, to pursue a PhD. On the university’s selection committee sat Khushwant Singh—already a well-known writer and affiliated with India’s Marxist party. Singh insisted that my father acknowledge and document Bhagat Singh as a Marxist in his thesis. The communist party, which had previously dismissed Bhagat Singh and his comrades as anarchists, was now eager to claim them as their own national heroes. My father refused, maintaining that Bhagat Singh had never expressed Marxist leanings.

It is worth noting that Khushwant Singh’s mother, Shobha Singh, had been the one to identify Bhagat Singh and Batukeshwar Dutt following the Lahore Assembly bombing. While the young revolutionaries did read books by Karl Marx—many of them brought by Sukhdev’s sister, a lawyer and activist—they never accepted Marxist philosophy. They studied such works only as a means of learning how to organize a resistance movement.

This same sister played a significant role in supporting the group. She frequently visited the DAV College hostel, helped the students obtain books they could not afford, and continued to support them even after their arrests. She recovered the bodies of Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev, and Rajguru after their executions, and even arranged for my father to complete an FA degree through correspondence while in prison.

Upon his release, the British imposed strict conditions: he could not live in a major city or associate with freedom fighters. For five years he lived in the remote village of Mohala, J&K, continuing his studies by correspondence and working toward a bachelor’s degree in history. Some courses, however, required in-person attendance, so in 1940 he petitioned the British government to allow him to move to Lahore to complete his degree at DAV College. The government agreed—not out of goodwill, but pragmatism. Constant surveillance of my father in Mohala was expensive; allowing him to study in Lahore reduced the cost of monitoring him. Two policemen were still assigned to watch him, but this was far less of a burden to the colonial administration.

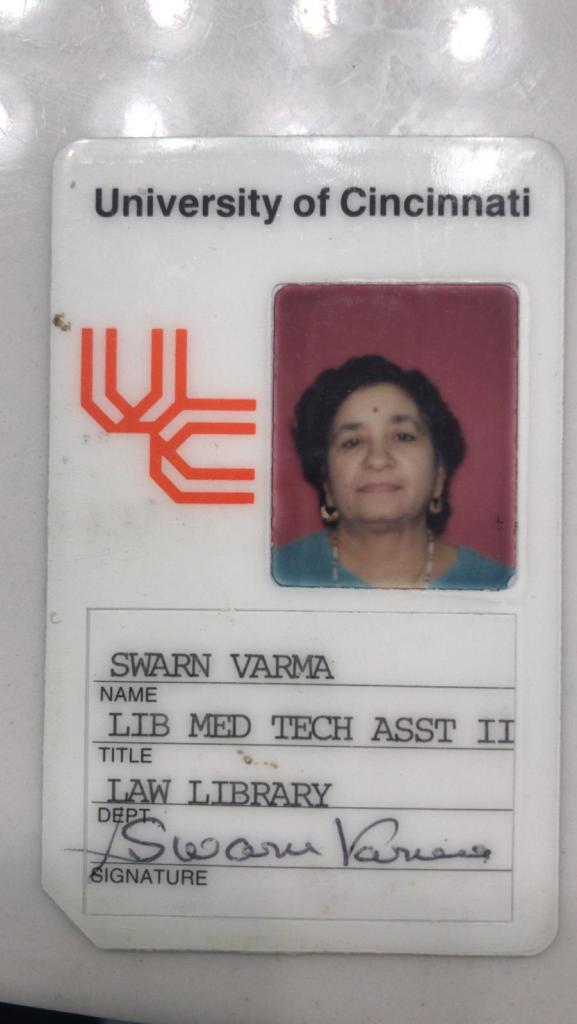

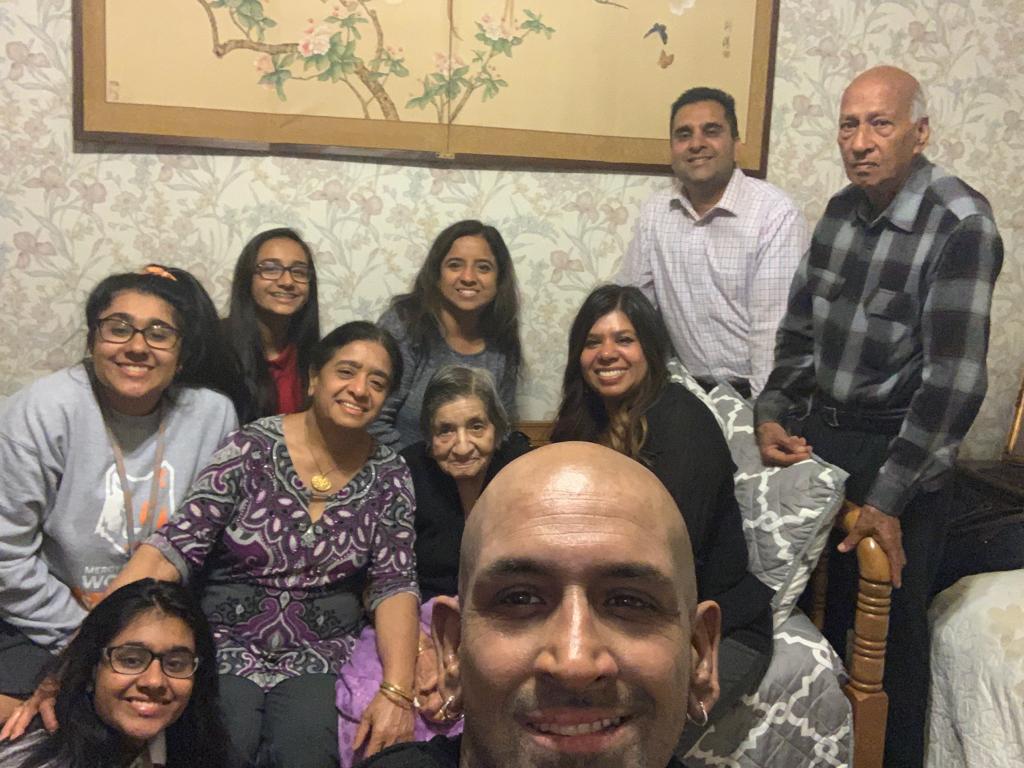

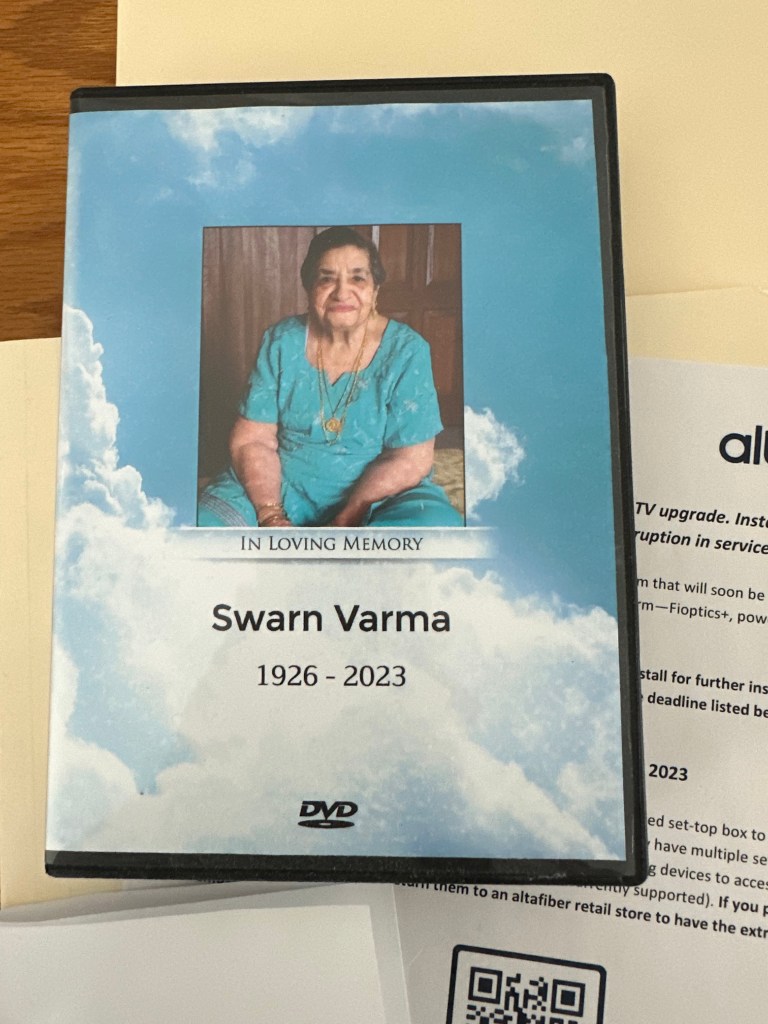

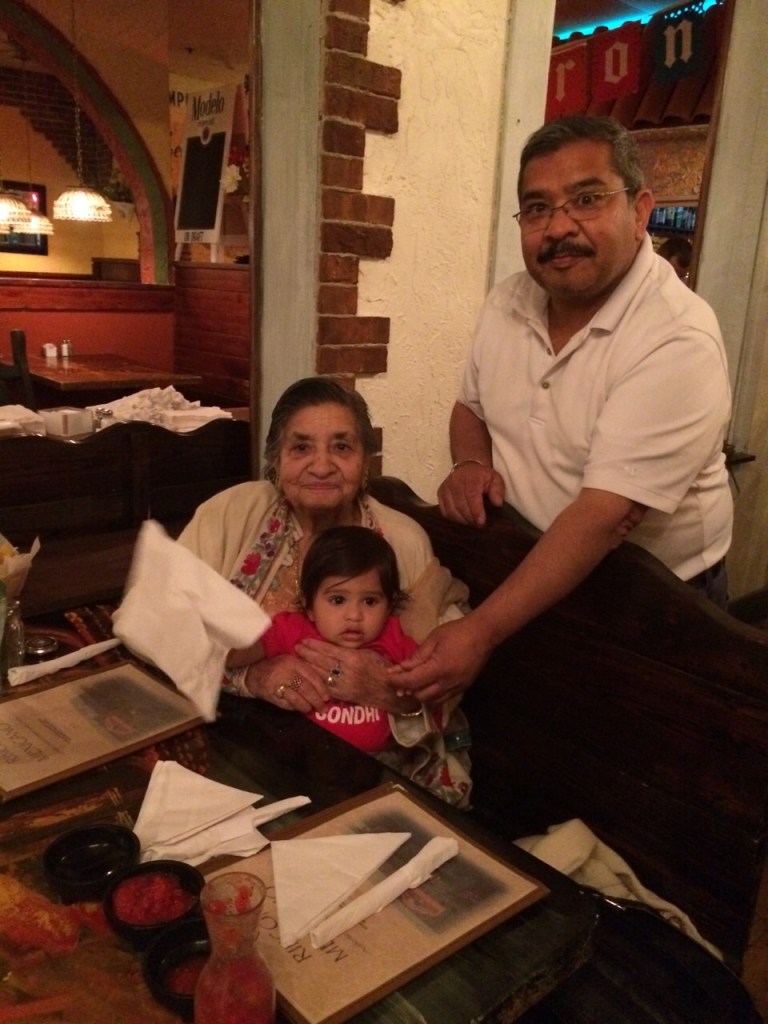

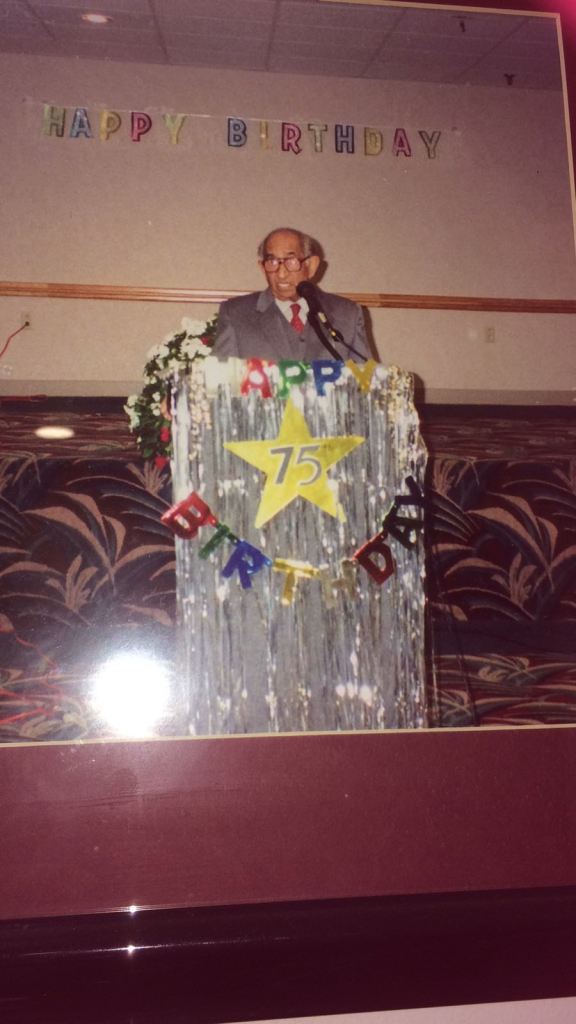

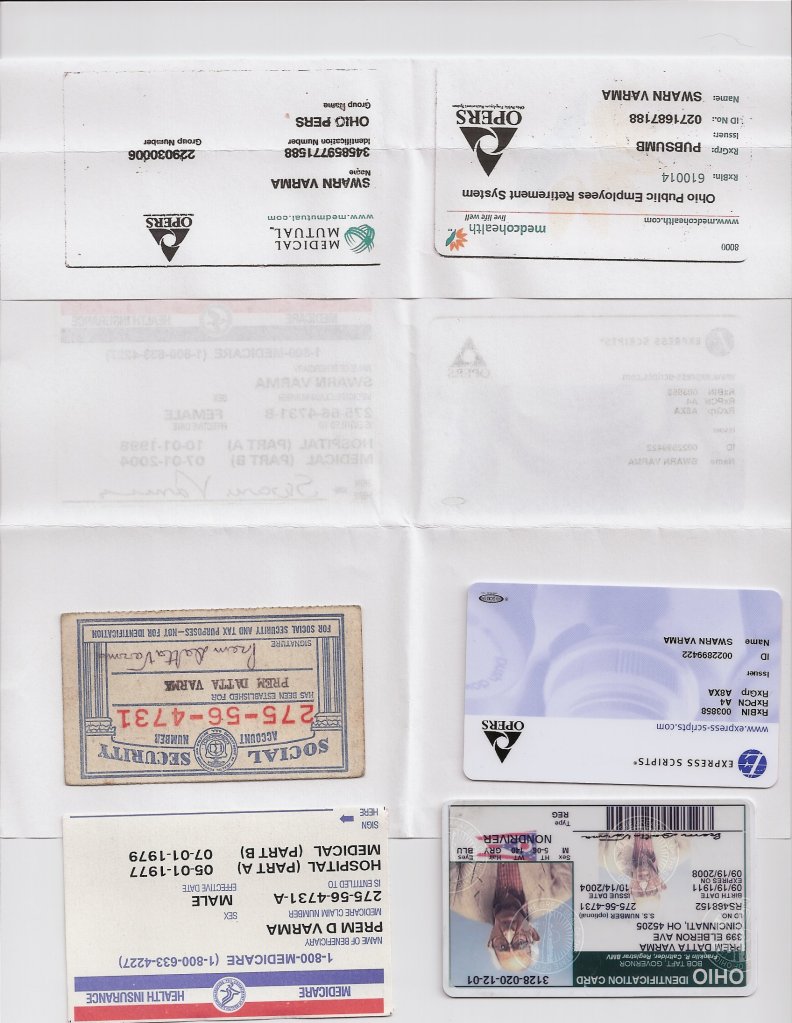

Although denied the chance to pursue doctoral studies in India, my father never abandoned his dream. Years later, after migrating to the United States, he finally earned his PhD in history from the University of Cincinnati—at the remarkable age of 74.

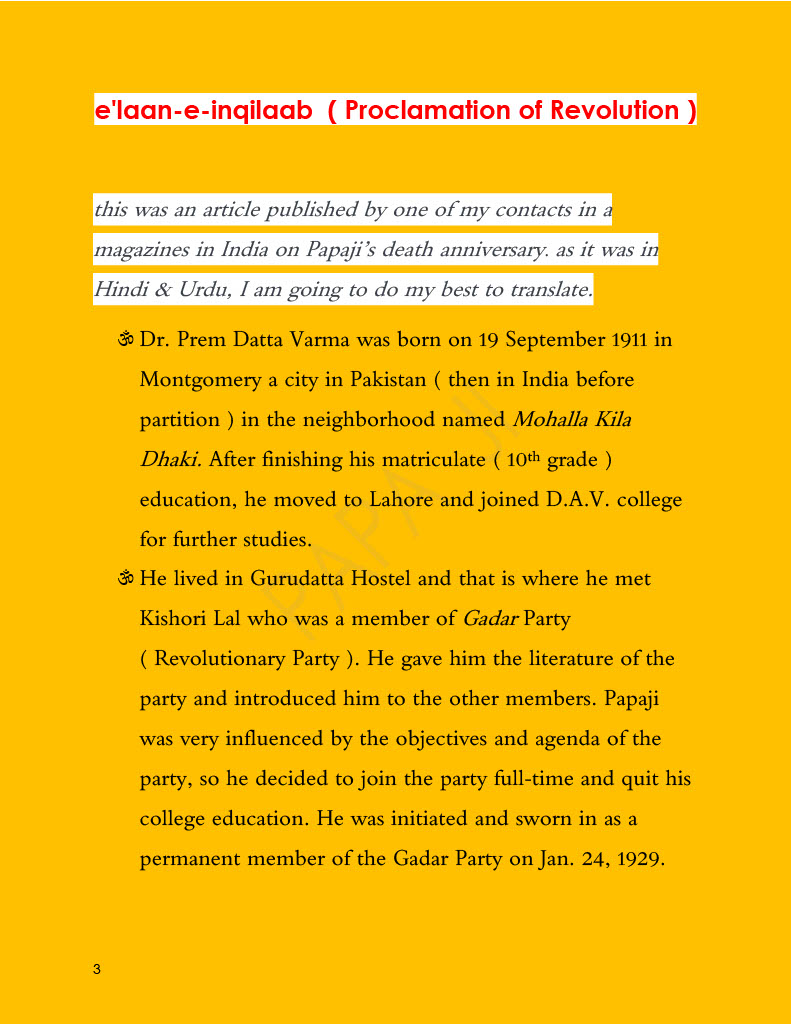

- Party moved him to Firozpur, a town in Punjab. He lived an anonymous life in TURHI BAZAAR under fictitious names such as Ram Nath & sometimes Amrit Lal to hide his true identity. He also rented a room in Patwaarian Mohalla of Firozpur.

- After the famous Lahore Assembly bomb incident several members of the party were arrested including Kishori Lal. On 20th April, papaji left Firozepur and went to Lahore. His assignment was to hide or destroy any secret documents related to the party in secret hide-outs in Lahore. He saved some of the important documents and left for his hide-out in Firozepur.

- On 5th May 1929, papaji was arrested with several incriminating documents and other objectionable stuff related to the anti -British government activities by the party.

- On 16th June 1929 papaji was charged and he admitted in court that he was in Firozepur to learn typing on party’s direction.

- Sometimes in 1930 the trial began in Lahore court and all the arrested party members were remanded into British Police custody. They were regularly beaten and tortured in police custody.

- One of the comrades Jaigopal could not take this regular beatings, humiliations, and torture, so decided to become approver or Government witness. he disclosed lots of party secrets and party members secret hide-outs. Several other members were arrested on his disclosures. He was rewarded with better living quarters and started receiving special privileges.

- During the trial while sitting in the witness stand, he used to taunt and tease other convicted members of the party by twisting his moustache. Papaji could not tolerate this showing off by a traitor and a coward. He was nothing but a weak link. One day while he was looking at Bhagat Singh and twisting his moustache, papaji took off his slippers ( chappals ), aimed towards Jaigopal head, and threw. That hit his face. At this Bhagat Singh said, “what an aim and a good shot. Hit him with the second one too.” But before papaji could take his second slipper out, police apprehended all the comrades and escorted them out of court. And the beatings, the torture continued just more harshly.

- 7th October 1930, papaji was sentenced to 5 years of harsh imprisonment in Montgomery British Federal Prison in connection with famous historical Lahore Conspiracy Case.