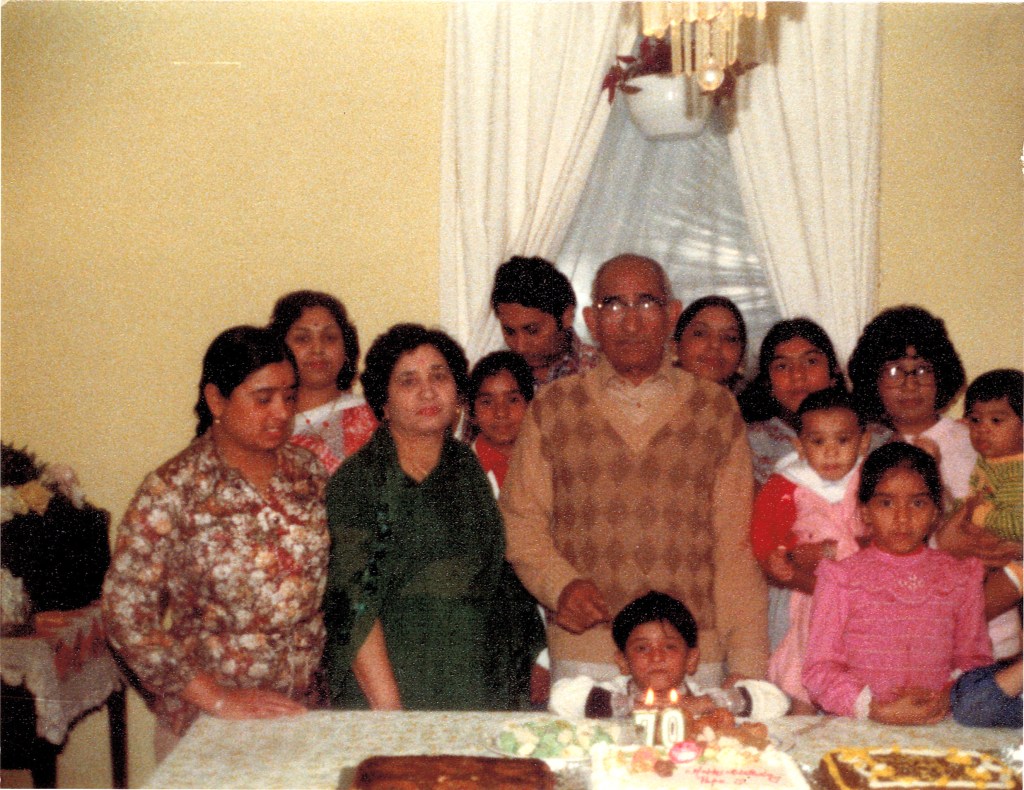

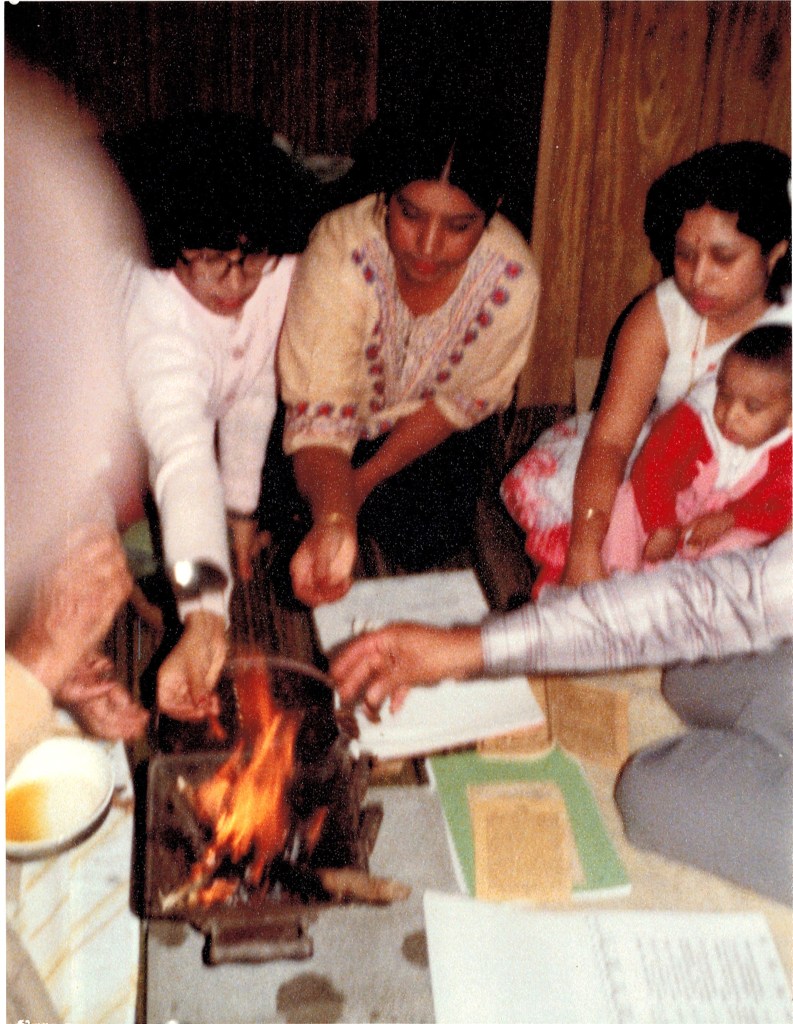

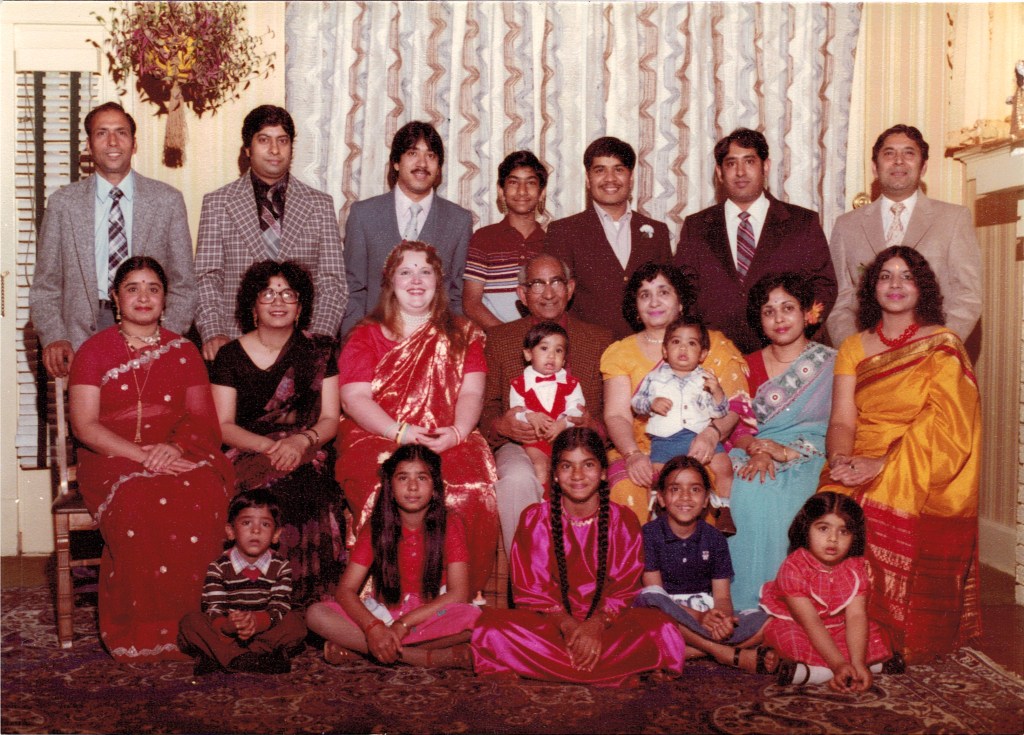

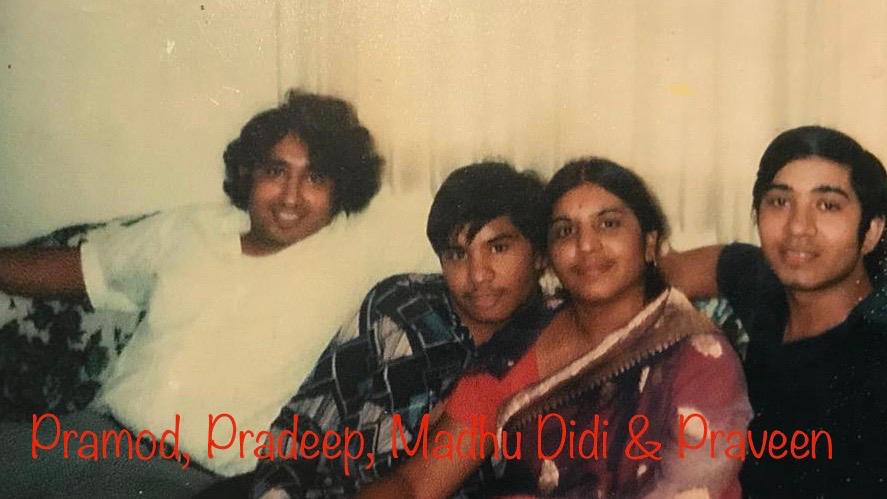

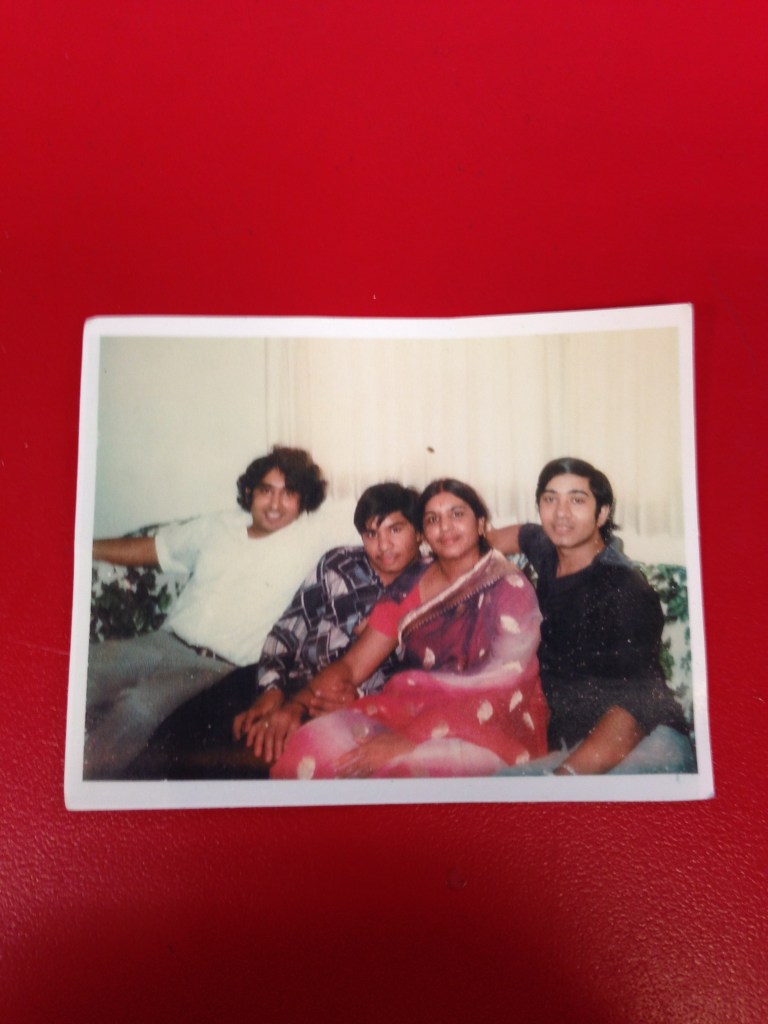

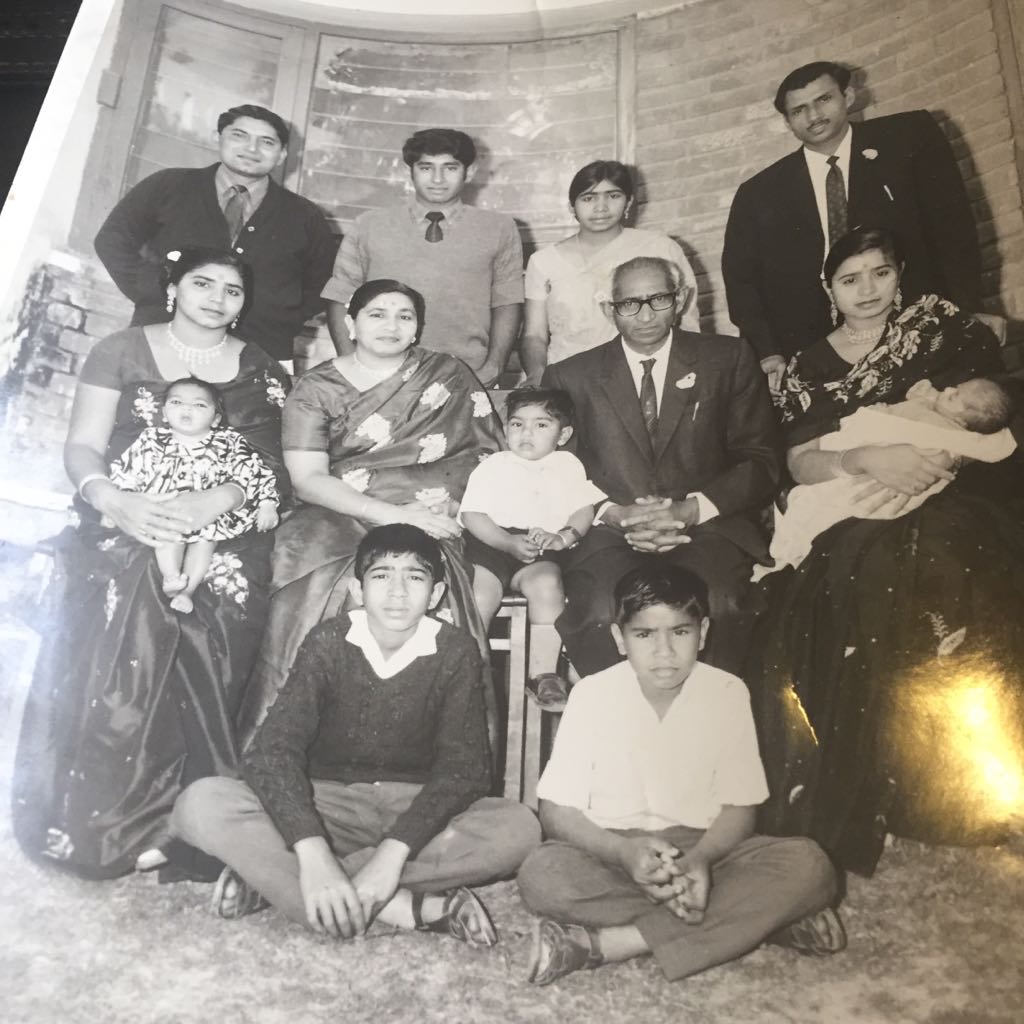

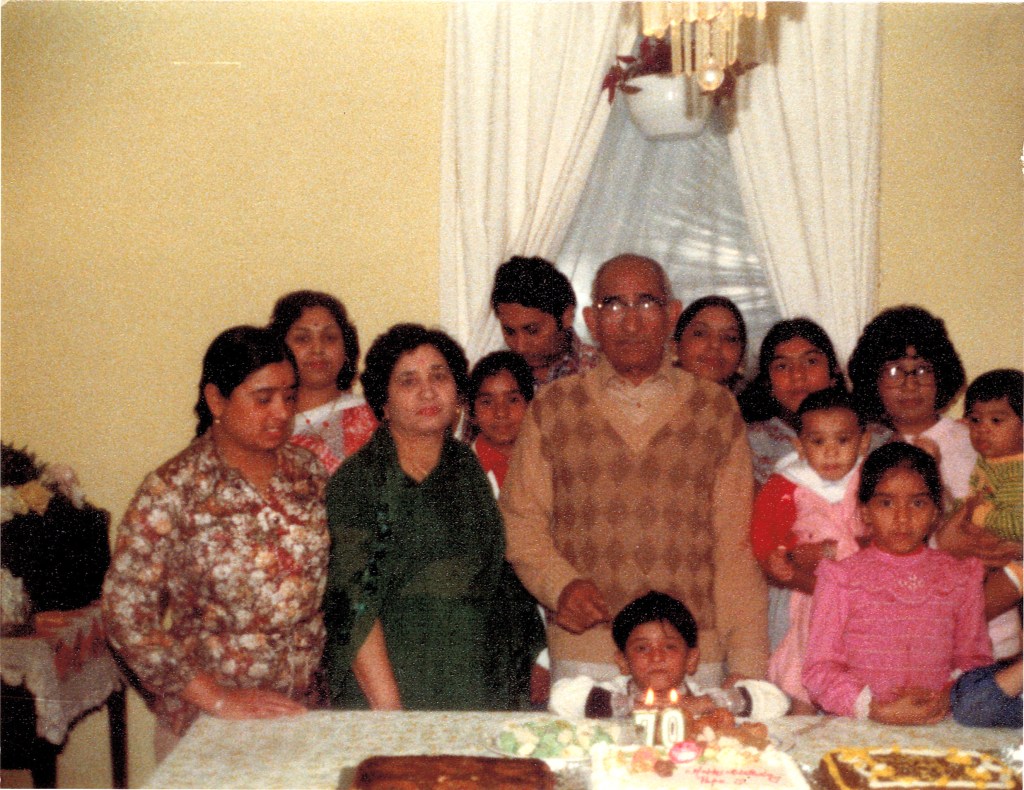

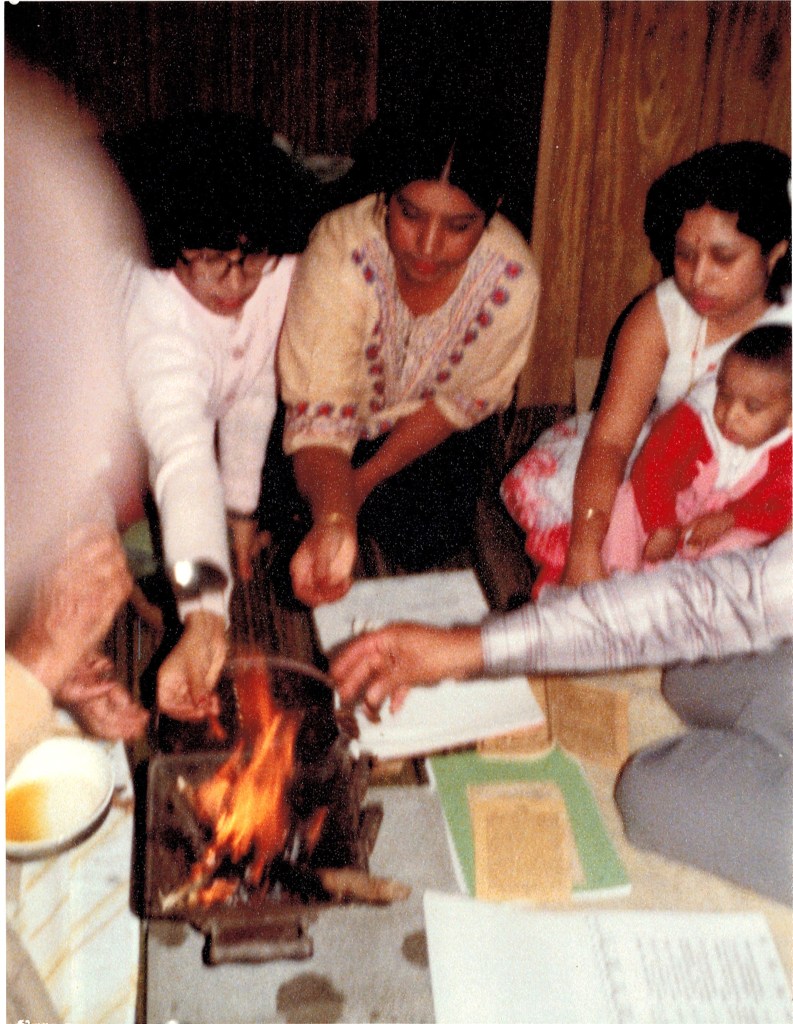

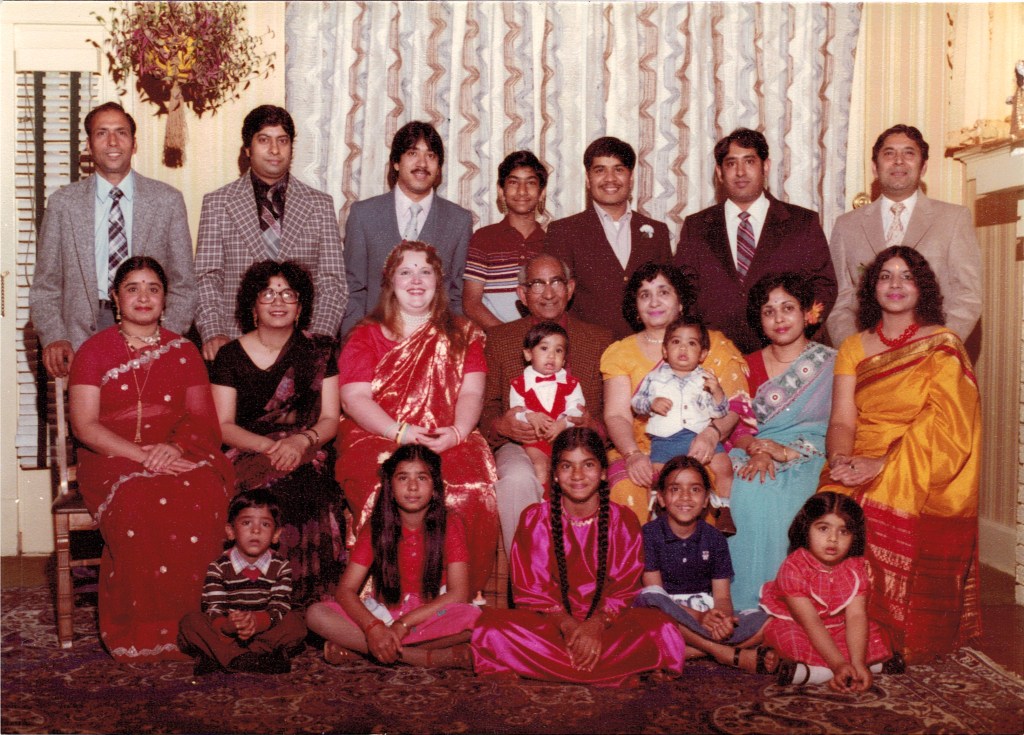

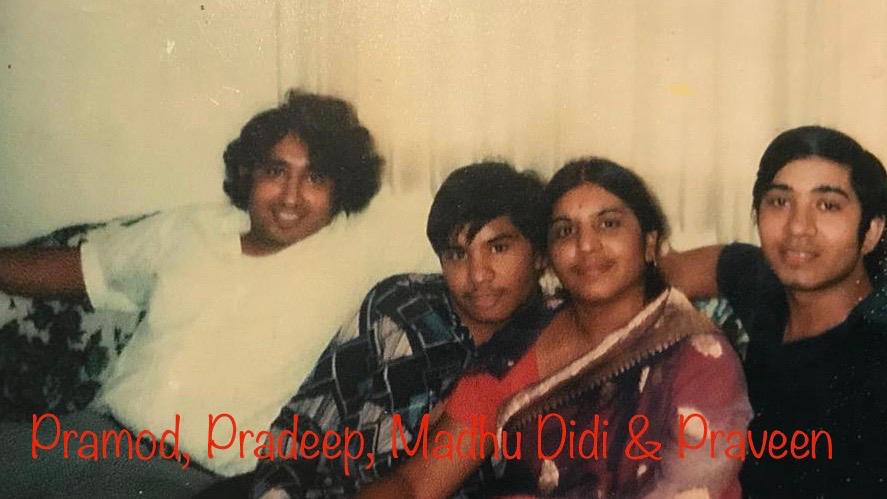

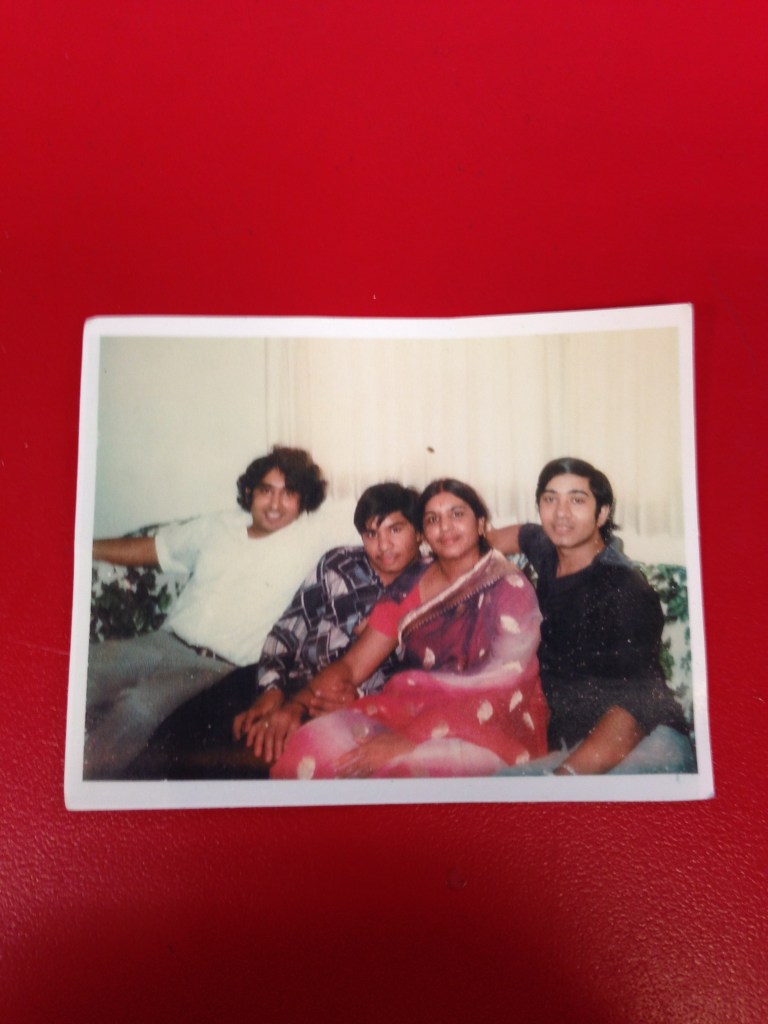

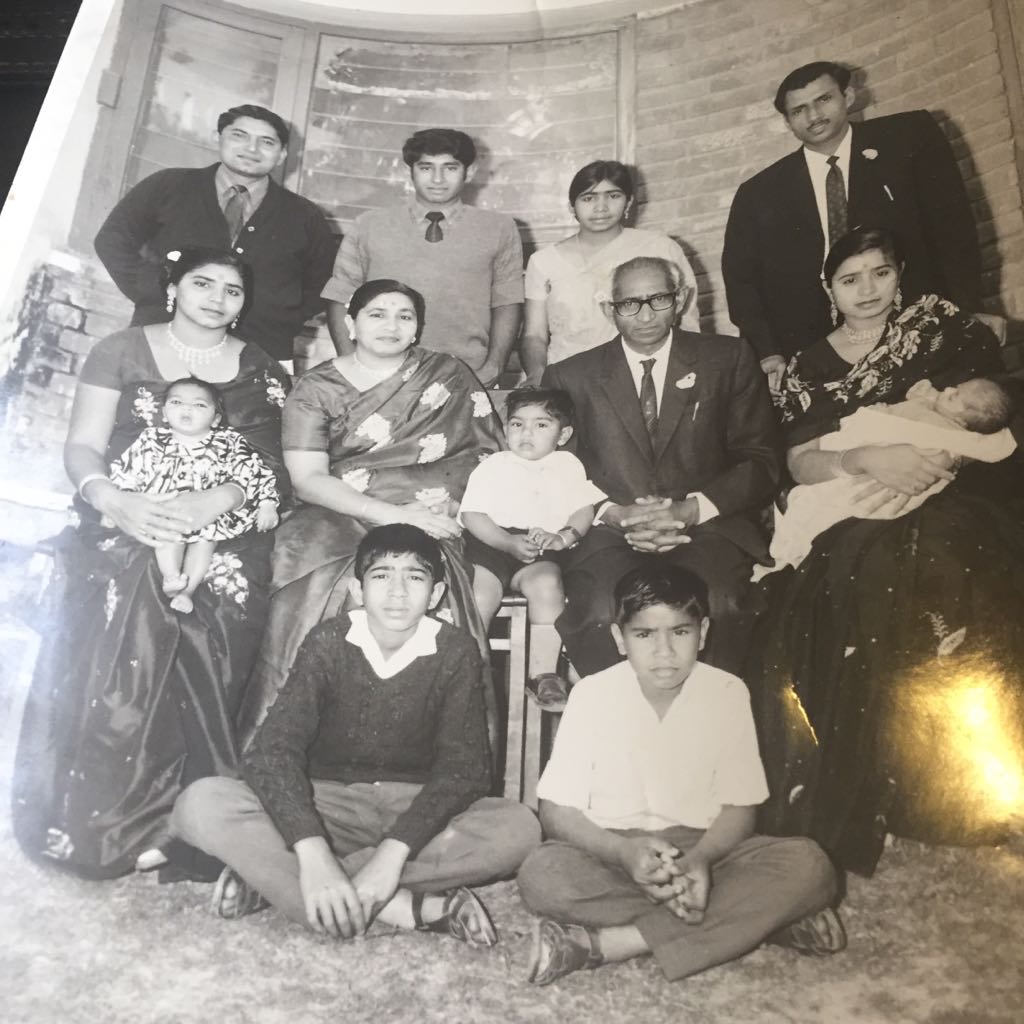

From Left to right Meena Sondhi, Pradeep Varma, Manju Soni, Praveen Varma, Beloved Nanaji (Swarn Varma) Me Pramod Varma, Shashi Khanna

Nanaji written prayer by Manju

it was a torture to see her like this. RIP nanaji

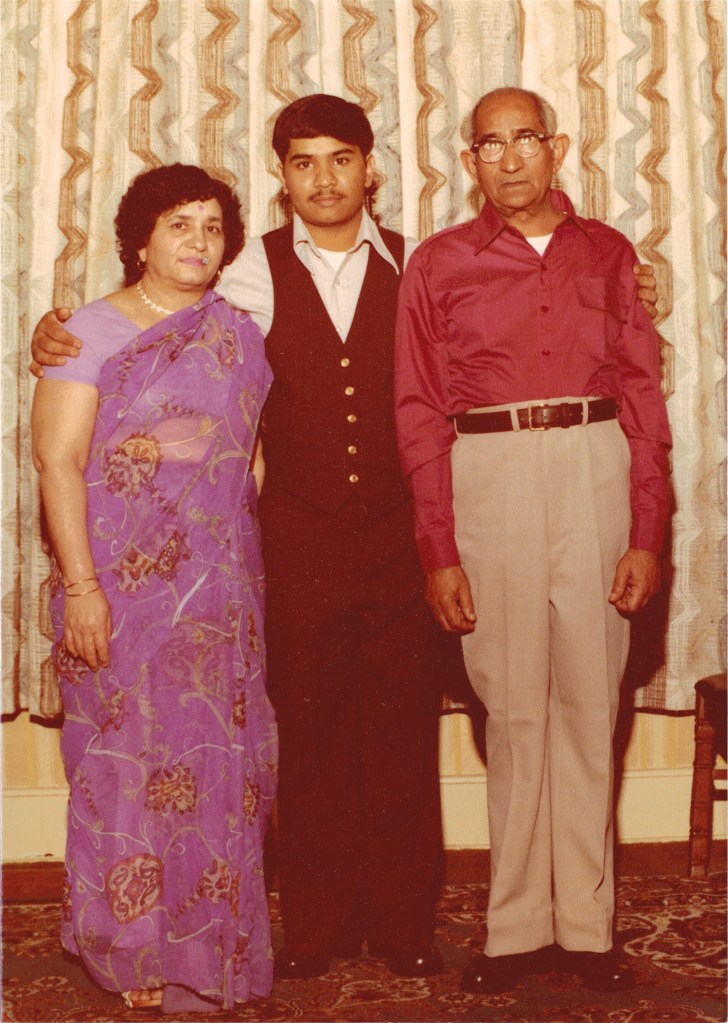

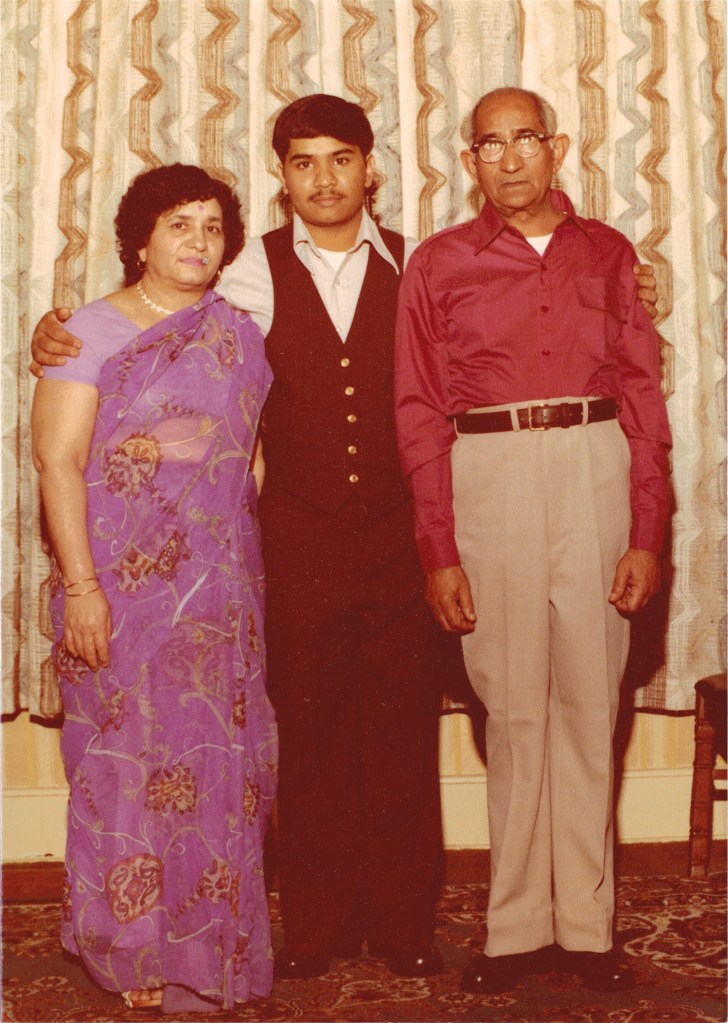

PAPA JI Intro

RaheN Na RaheN Hum ( रहें न रहें हम, महका करेंगे )

ॐ Papa Ji

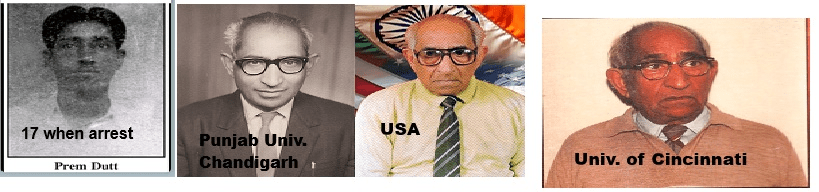

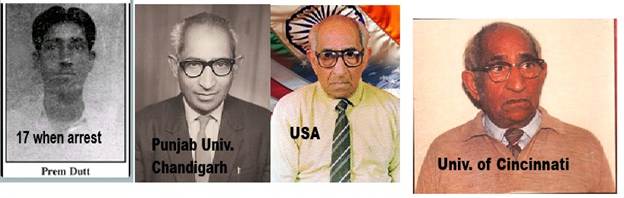

Dr. PREM DATTA VARMA

After graduating from high school in Jammu, he continued his education at D.A.V. College in Lahore. At the time, Lahore was a hub of political activity, and the college was deeply influenced by the ideals of the Arya Samaj movement. Lala Lajpat Rai, a prominent Arya Samaj leader, freedom fighter, and close family friend, was a frequent speaker at D.A.V. College. Papaji often attended his lectures with admiration. One of the defining moments of his early life occurred when he was standing beside Lala Lajpat Rai during a peaceful protest against the Simon Commission. That day, British Police Officer Saunders brutally attacked Rai with a baton, fatally injuring him. Papaji not only witnessed this tragedy firsthand but also helped prepare the arthi (funeral bier) for the great leader. This incident left a deep impression on him and became a turning point in his life. It was then that he made a personal vow to dedicate himself to India’s freedom struggle and to contribute in whatever way possible to ending British colonial rule.

Many other young students in Lahore were also stirred by the incident, among them Chandrashekhar Azad, Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev, Bhagwati Charan Vohra, and Kishori Lal. Kishori Lal, who was already active in the revolutionary Ghadar Party, personally recruited Papaji into the movement. Soon, he developed a particularly close bond with Sukhdev, who was not only his comrade but also his hostel mate at D.A.V. College. While Papaji was studying chemistry, the party gave him a crucial responsibility: assisting Bhagwati Charan in preparing bombs. Because of his excellent handwriting, fluency in both Hindi and English, and background in science, he was entrusted with the task of copying the bomb-making formula and procedures. His meticulous handwriting was, in fact, the one preserved on the original documents used by the revolutionaries.

His active involvement eventually led to his arrest. He was caught while riding a bicycle, carrying a bag filled with bomb shells that had been made with the help of an ironsmith in Ferozepur. Convicted alongside Bhagat Singh, he was sentenced to five years of rigorous imprisonment in Montgomery Jail. Despite the sentence, he was released after serving four years. His freedom, however, came with restrictions: he was prohibited from residing in any metropolitan city where he could reconnect with other students or political activists. Two policemen were assigned to watch him at all times, and he was forced to live in a remote village in Doda district, Jammu and Kashmir.

Even under such surveillance, Papaji used his time productively. Through correspondence, he completed his F.A., and during this period, history became his passion. While living in remote parts of Jammu and Kashmir, he also worked to establish Arya Samaj centers. These activities, however, made him unpopular among the local Muslim population, but he continued his work with conviction. Eventually, he was permitted to return to Lahore, where he completed his higher studies and earned an M.A. with honors in History.

At D.A.V. College, he quickly rose to leadership roles, becoming a member of the student council. Among his most notable contributions was arranging a debate between two towering political figures of the time: Muhammad Ali Jinnah and Jawaharlal Nehru. It was during this historic debate that Jinnah publicly articulated, for the first time, the idea of dividing India along religious lines, declaring his unwillingness to share power with Nehru. This event foreshadowed one of the most consequential developments in modern Indian history—the partition of India.

Alongside his academic and political pursuits, he became a dedicated member of the Rashtriya Swayam-Sevak Sangh (RSS). He took pride in founding the very first RSS shakha at D.A.V. College in Lahore. During the chaos of partition in 1947, he witnessed the horrors of communal violence firsthand, yet he actively worked to protect and escort Hindu families as they migrated from Pakistan to India. The bloodshed and massacres of that period left an indelible mark on him, reinforcing his commitment to community service and national unity.

In 1948, when armed infiltrators from Afghanistan and Pakistan invaded Jammu and Kashmir, the situation became dire. These “Kabaliye” were supported by the Pakistani state and regular army disguised in civilian clothes, aiming to destabilize the region and prevent a plebiscite that could have favored India. Prime Minister Nehru was hesitant to deploy the Indian Army formally since Jammu and Kashmir was technically still an independent princely state. At the informal request of Sardar Patel, however, the RSS organized militias of Swayam-Sevak to resist the infiltrators. Papaji was assigned the dangerous responsibility of transporting arms and ammunition supplied by the Indian Army to the front lines.

During one such mission, he was shot in the leg. Because the police were searching for him, he could not seek treatment in a government hospital. Even his own uncle, a physician in a civil hospital, refused to help him out of fear of losing his government job. In the end, his fellow swayamsevaks—who were not trained surgeons—removed the bullet from his knee without anesthesia. Later, after Maharaja Hari Singh formally signed the Instrument of Accession, Jammu and Kashmir became part of India. By chance, Papaji was on the same plane as the government official who carried this historic document from Srinagar to New Delhi, and he saw it before it was even presented to India’s political leadership.

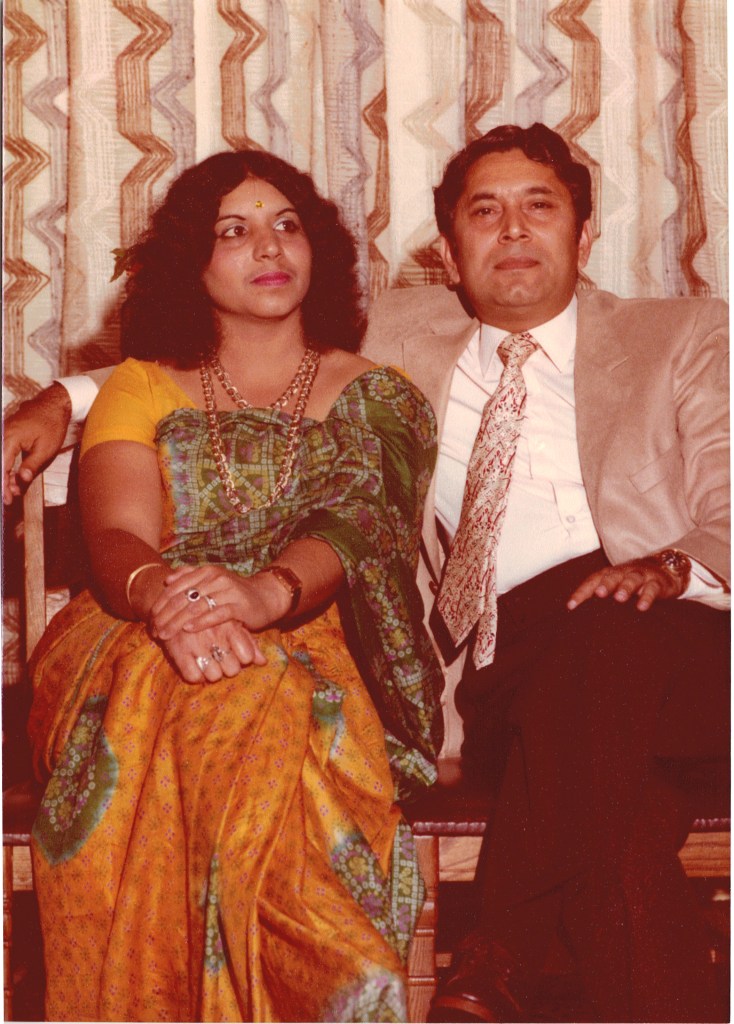

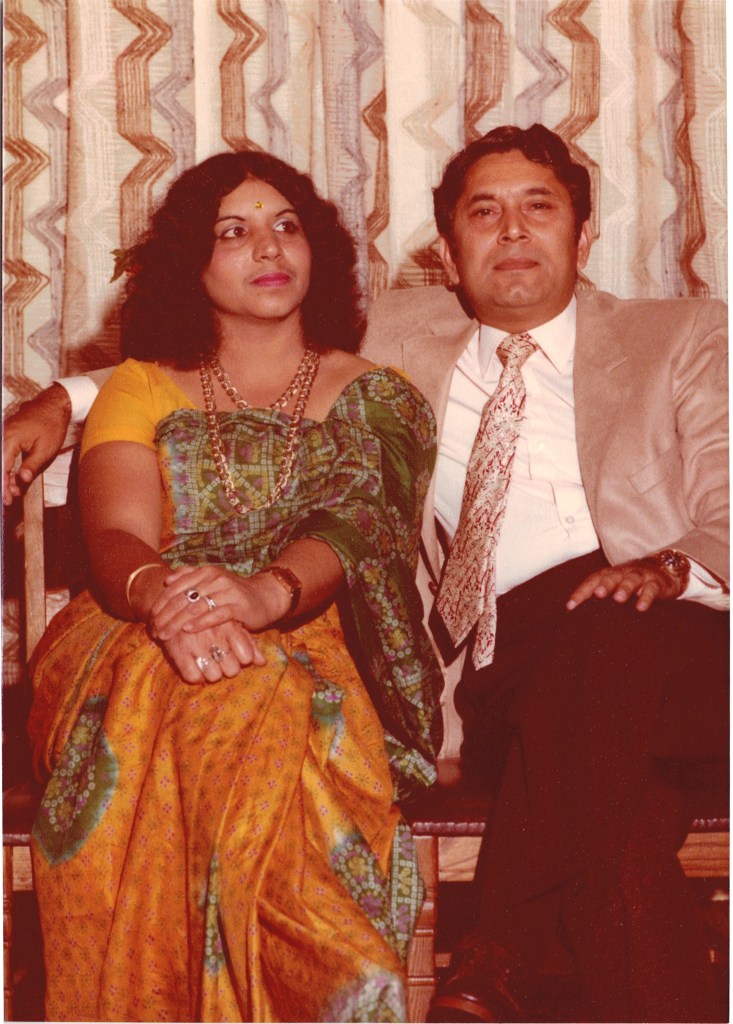

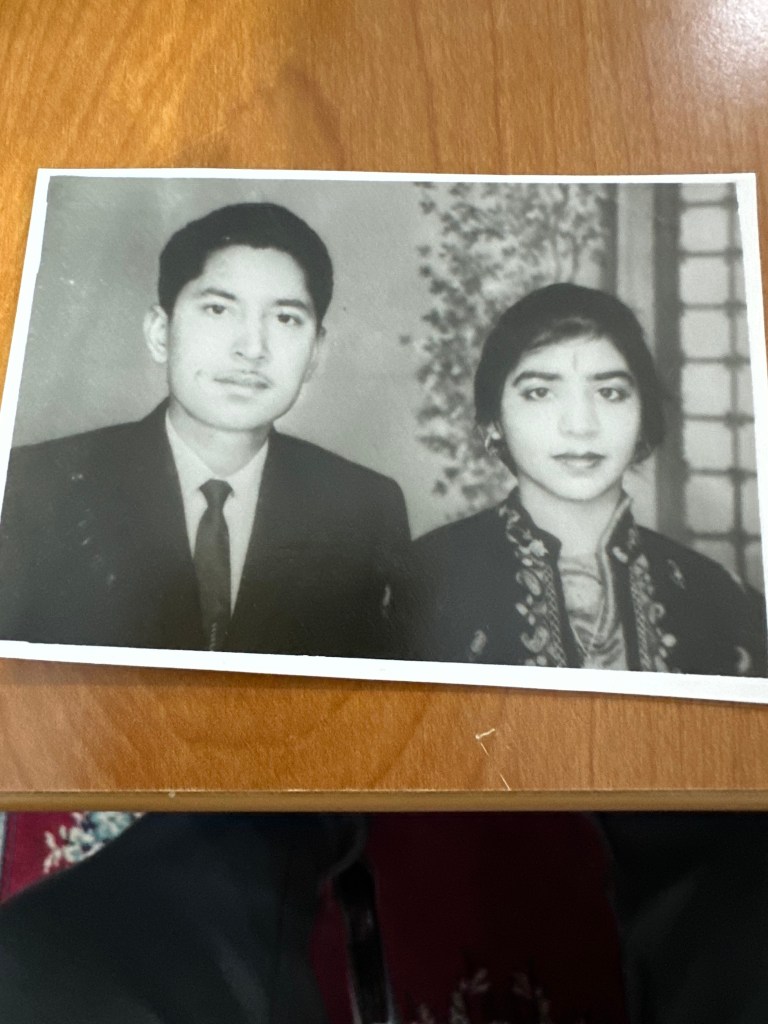

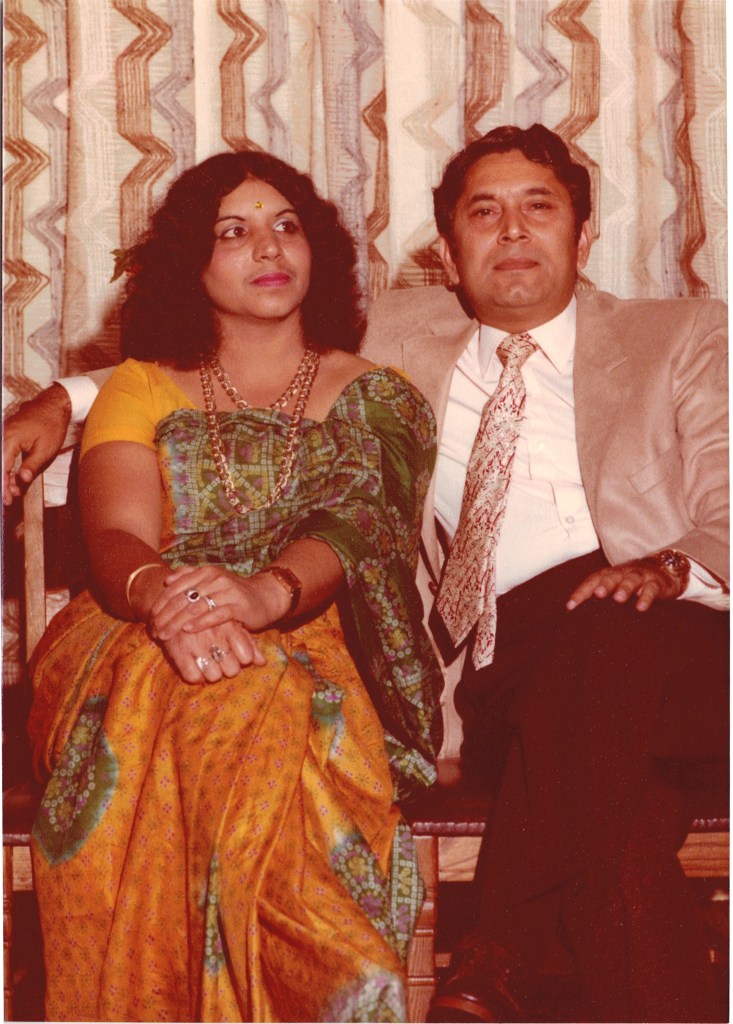

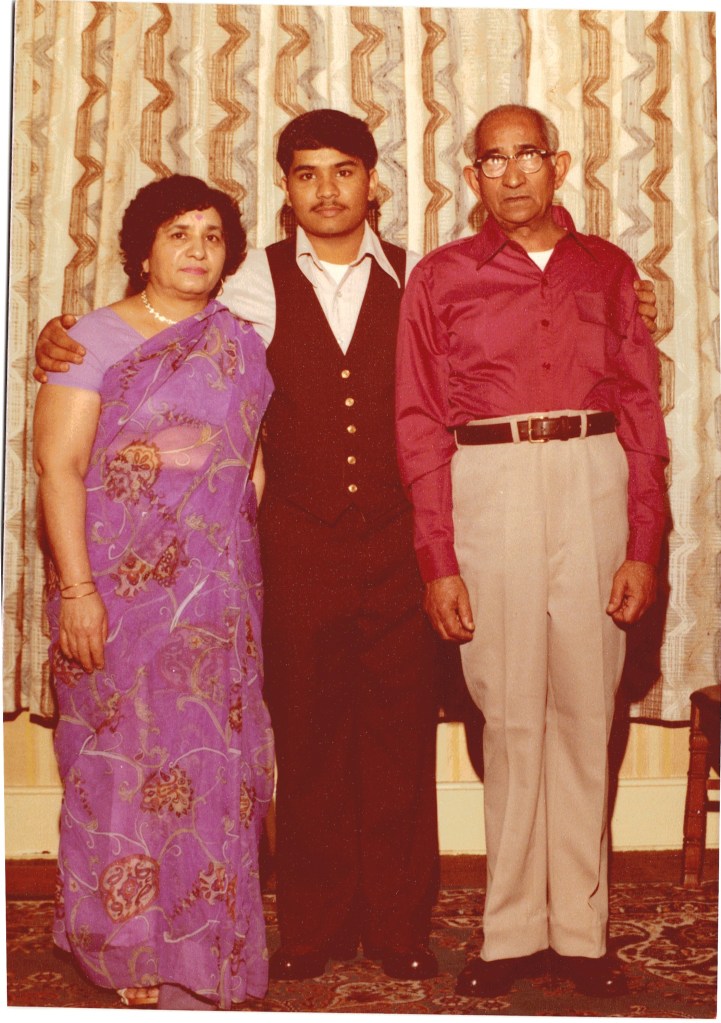

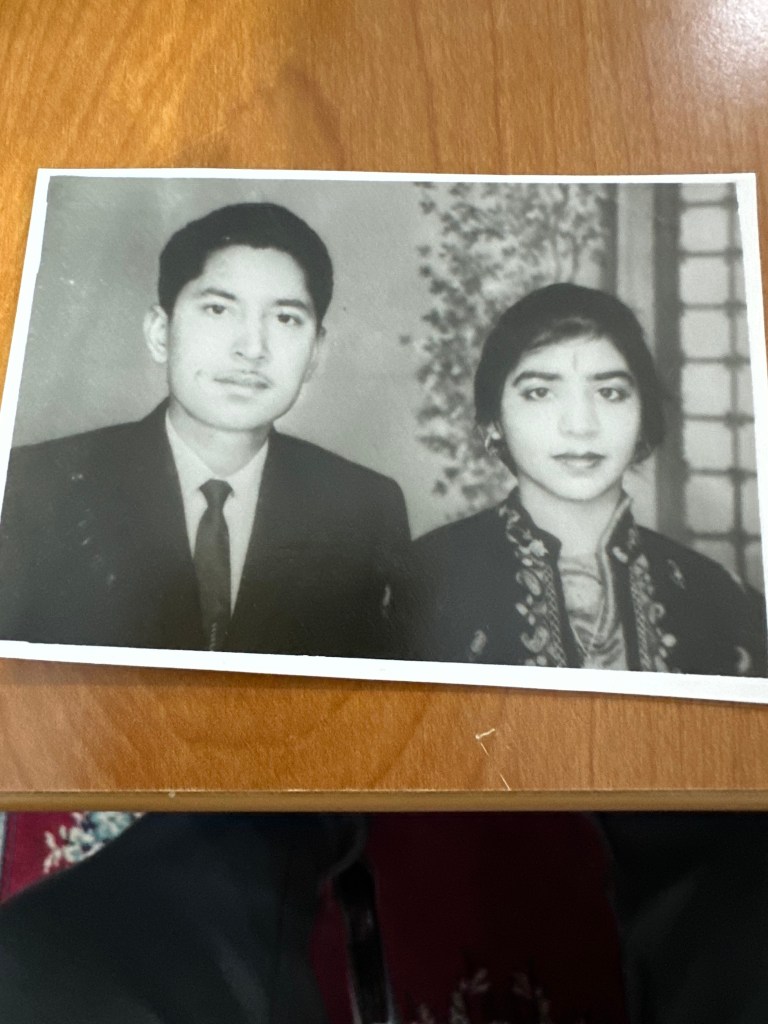

Amid all these struggles, he also built his personal life, marrying in 1946. After partition, he pursued his academic career, teaching history first at Government College in Moga and later at Doaba College in Jalandhar. In 1960, he joined Punjab University in Chandigarh as a lecturer. Over time, he made significant contributions to the field of history. He authored History of British India, co-authored Mughal India, and wrote The Battles of Panipat. He also translated several important English history texts into Hindi, making them accessible to a broader audience. In addition, he served as the editor of the Punjab University monthly bulletin.

In 1970, at the age of 59—an age when most people begin planning for retirement—he chose instead to embark on a new chapter of his life by moving to the United States. Despite his accomplishments, his political affiliations had hindered his academic growth in India. He was denied the opportunity to complete his Ph.D. at Punjab University because of his association with the Jan Sangh. Khushwant Singh, a well-known writer and member of the Communist Party, who was also a senator on the Punjab University Historical Council, openly opposed him. Singh even told him that unless he severed ties with the Jan Sangh, he would never be allowed to earn a doctorate as long as Singh held power.

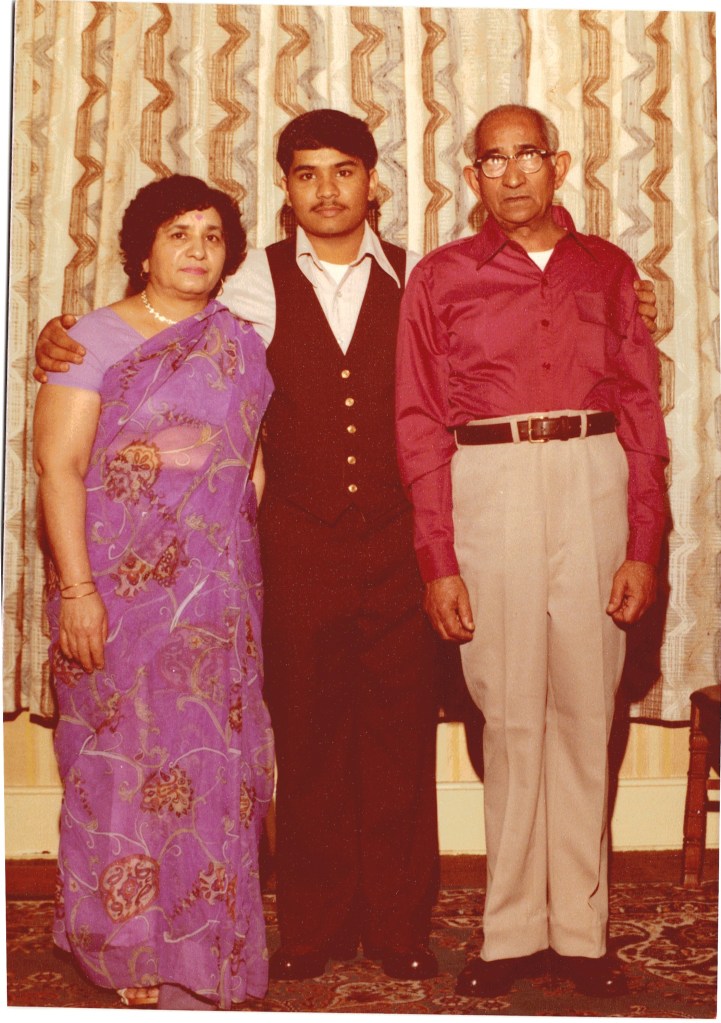

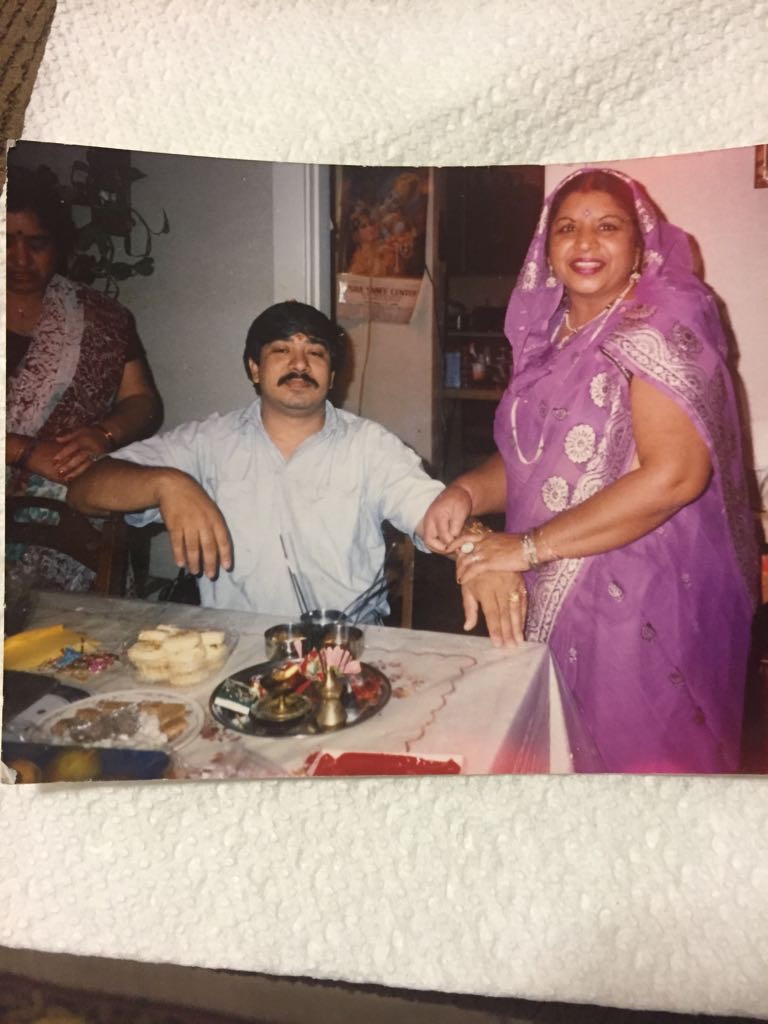

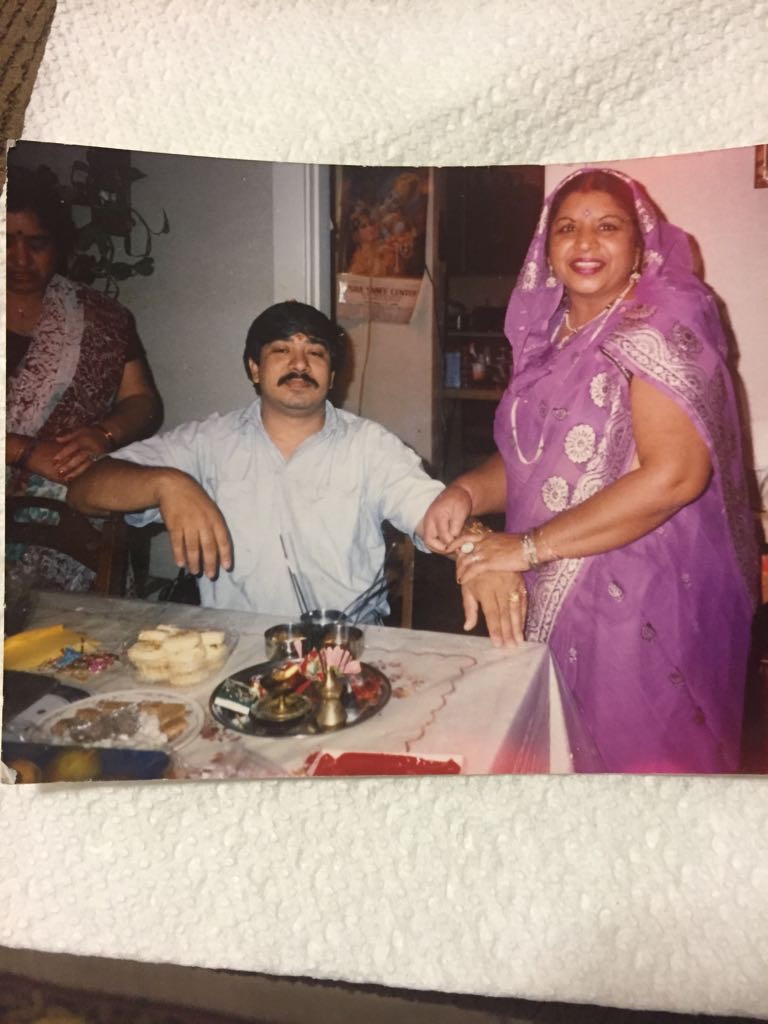

Undeterred, Papaji pursued his dream abroad. At the University of Cincinnati, he finally completed his Ph.D. at the remarkable age of 74, becoming the oldest recipient of a doctorate in the university’s history. His dissertation focused on the Early History of Migration from the Indian Subcontinent to the USA. He also took great pride in publishing and editing his father’s research work, Vedic Language is the Root of All Languages. Beyond academics, he served the Indian community in America, working as treasurer of the Hindu Society of Greater Cincinnati and as the first editor of Aradhana, the society’s magazine.

In the final years of his life, his health began to decline. His vision failed, making it impossible for him to read—a cruel fate for a man who had spent his entire life surrounded by books. Walking, once his favorite activity, became difficult. This was particularly heartbreaking for someone who had once walked long distances—from Doda to Batote, and even from Lahore to Amritsar during partition. Dementia slowly eroded his memory. A man who had dedicated his life to history, who could recall with precision the dates of battles and revolutions, began forgetting the names of his own children. He survived cancer but eventually needed help with even the most basic tasks, such as walking to the bathroom.

Yet, despite the toll that time took on his body and mind, his life was never without purpose. Every chapter, from his revolutionary youth to his academic achievements and his service to the community, reflected a deep commitment to his country, his people, and his ideals. His journey was one of resilience, sacrifice, and devotion—a testament to how one life, lived with conviction, can become part of the very history he so passionately studied.